ALSO BY MARK WYMAN

Hard Rock Epic: Western Miners and

the Industrial Revolution, 18601910

Immigrants in the Valley: Irish, Germans, and Americans

in the Upper Mississippi Country, 18301860

DPs: Europes Displaced Persons, 19451951

Round-Trip to America:

The Immigrants Return to Europe, 18801930

The Wisconsin Frontier

HOBOES

HOBOES

BINDLESTIFFS, FRUIT TRAMPS, AND

THE HARVESTING OF THE WEST

MARK WYMAN

HILL AND WANG

HILL AND WANG

A DIVISION OF FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX

NEW YORK

Hill and Wang

A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright 2010 by Mark Wyman

Maps copyright 2010 by Jill Freund Thomas

All rights reserved

Distributed in Canada by D&M Publishers, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2010

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wyman, Mark.

Hoboes : bindlestiffs, fruit tramps, and the harvesting of the West / Mark

Wyman. 1st. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8090-3021-7 (hbk. : alk. paper)

1. TrampsWest (U.S.)History. 2. Migrant laborWest (U.S.)History. 3. West (U.S.)History18601890. 4. West (U.S.)History18901945. I. Title.

HV4504.W96 2010

305.5'68dc22

2009020834

Designed by Jonathan D. Lippincott

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This book is dedicated

to all those who have

helped me know,

and love, the American West

CONTENTS

THE NEW WEST

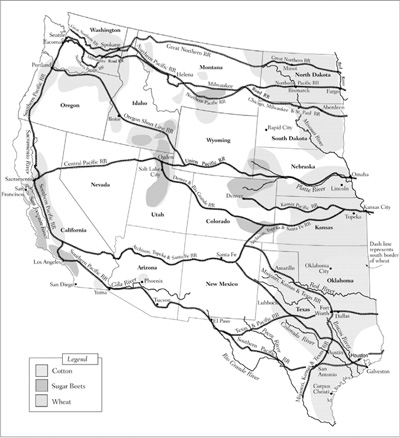

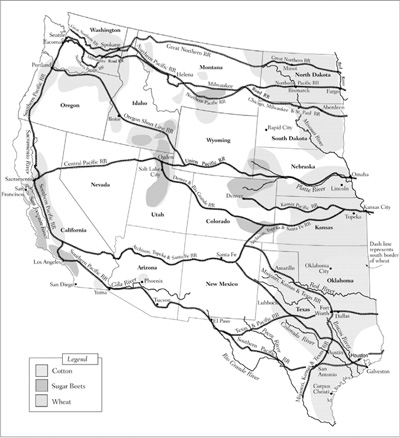

Major railroads and important areas of cotton, sugar beets, and wheat.

GREAT PLAINS AND THE SOUTHWEST

Wheat, sugar beets, and cotton dominated different areas.

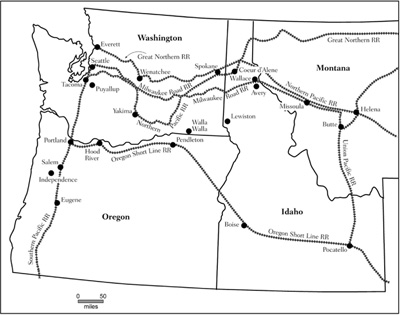

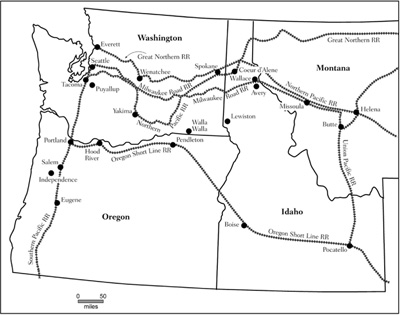

PACIFIC NORTHWEST

Wheat, hops, apples and other fruit, and logging became major products after the arrival of the railroads.

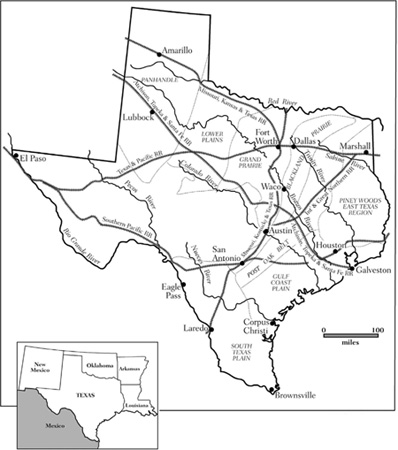

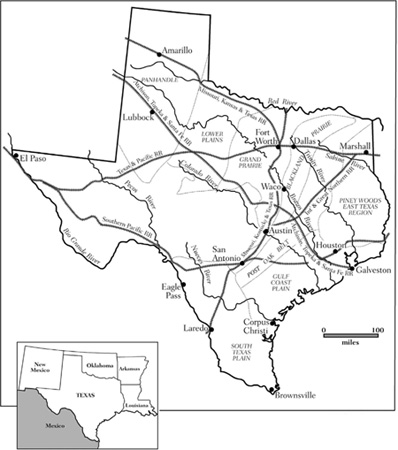

TEXAS

Railroads helped cotton spread west from the Gulf Coast and Piney Woods.

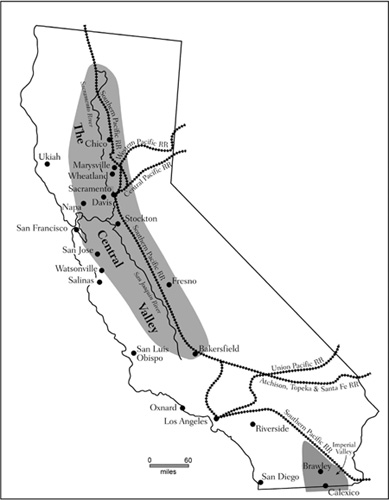

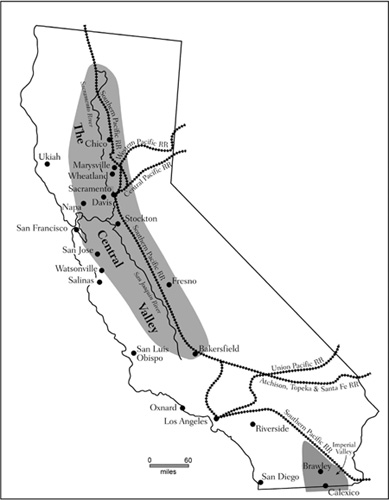

CALIFORNIA

Wheat gradually gave way to fruit, hops, and cotton.

INTRODUCTION

It was not just the long line of mensome two hundred of thembeing marched by Aberdeen police from one railroad crossing to another and told to grab a freight out of town. And it was something more than seeing the Aberdeen Commercial Club packed full of men, honest-looking men, begging for work with no questions as to wages, while farmers in that area of South Dakota for miles around in all directions were supplied with all the harvest hands they could use.

No, in that summer of 1914 what mainly bothered the agent from the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations was that only a few weeks earlier the federal government had called for thousands of harvest hands to come to the Great Plains12,000 to 15,000 for Oklahoma, it was said, then 30,000 more for Missouri and 40,000 for Kansas. Notices calling for more and more workers were sent to postmasters to affix in a conspicuous place, and the Aberdeen Daily News announced that 82,000 more men were needed throughout the wheat belt: Harvest Fields Offer Opportunity for Unemployed of the Cities.

Special Agent William A. Duffus had to ponder all this as he surveyed the Aberdeen scene, with its saturation of harvest hands, even as calls went out for more: What kind of system would urge thousands of men to leave their homes and head to the harvest fieldswhen they were not needed? What basic design led men to flock blindly into the grain states, crowding into the larger and more easily accessible railroad centers, where labor needs were already filled, while smaller and more remote communities on the branch lines might be desperately in need of harvest hands?

If his employers at the Commission on Industrial Relations had doubts of the truth of his report, Duffus had a suggestion:

The commission should walk up and down the streets of little cities like Oakley and Colby, Kansas; Huron and Redfield, South Dakota; and Casselton, North Dakota, and watch the men who sit along the curbs in long rows, crowd the side walks, lean against buildings, and hang around the railroad stations waiting, waitingalways waitingfor some farmer to come into town to hire a hand; and note the hungry, tired, despondent and sometimes sullen looks on the faces of these men.

The probing questions asked by Agent Duffus that day in Aberdeen went to the heart of the transformation of the American West that began in the latter nineteenth century and ran fully two decades into the twentieth. It was brought first by the railroad as it coursed through plains and mountains and coastal districts, opening vast stretches to farming. Then came irrigation canals that, together with the railways, made possible new kinds of intensive agriculture with often strict demands on horticulture and science. Arizona cotton growers needed water from irrigation ditches and a nearby railroad to haul their product to distant marketsas did growers of Washington berries, Colorado sugar beets, and California oranges. The insects that thrived amid closely planted fruit trees had to be combated with the latest sprays. And once the fruit was carefully picked and packed, it had to reach consumersbut the markets for western produce were located far away, in the Midwest, in the East, even in Europe. With the iron horse, growers could now reach those markets. The pioneer West of Indians and mountain men had emerged into a Second Frontier, beyond the fur trade and cattle drives, where riches came not only from underground mines but also from topsoil. It was truly a new West, and it would soon become the nations granary, its bountiful orchard, the Cotton West, the Garden West.

What this new frontier lacked was laborers. The large scale of this new agriculture and the lack of nearby cities meant that not only was a hired hand inadequate for a farms summer and fall needs, but also that the vast numbers of seasonal harvesters required were not available close by. Instead, transients would have to do the work. They would have to show up in time and in large enough numbers to bring in the crop; then when the work was finished, they would have to clear out of the area; but, next season, they would be expected to return. The railroads role in moving them would be crucial.

Special Agent Duffus saw the worst side of this situation when he stumbled upon the police roundup at Aberdeen. Most of the new crops had only days to be harvested, and growers had no way to guarantee whether labor would be scarce or, as at Aberdeen in 1914, in oversupply. For western newspapers often told the opposite story: in 1906, just when Puyallup, Washington, was expecting one of its biggest raspberry crops, the

HILL AND WANG

HILL AND WANG