AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

GLOBAL ETHICS SERIES

General Editor: Kwame Anthony Appiah

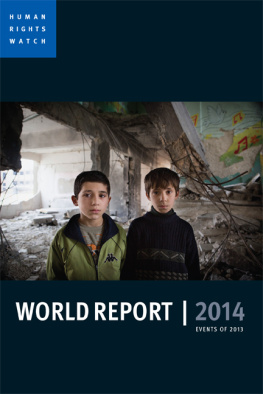

In December 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights and thereby created the fundamental framework within which the human rights movement operates. That declarationand the various human rights treaties, declarations, and conventions that have followedare given life by those citizens of all nations who struggle to make reality match those noble ideals.

The work of defending our human rights is carried on not only by formal national and international courts and commissions but also by the vibrant transnational community of human rights organizations, among which Amnesty International has a leading place. Fifty years on, Amnesty has more than two million members, supporters, and subscribers in 150 countries, committed to campaigning for the betterment of peoples across the globe.

Effective advocacy requires us to use our minds as well as our hearts; and both our minds and our hearts require a global discussion. We need thoughtful, cosmopolitan conversation about the many challenges facing our species, from climate control to corporate social responsibility. It is that conversation that the Amnesty International Global Ethics Series aims to advance. Written by distinguished scholars and writers, these short books distill some of the most vexing issues of our time down to their clearest and most compelling essences. Our hope is that this series will broaden the set of issues taken up by the human rights community while offering readers fresh new ways of thinking and problem-solving, leading ultimately to creative new forms of advocacy.

FORTHCOMING AUTHORS:

John Broome

Philip Pettit

John Ruggie

Sheila Jasanoff

Martha Minow

THE HUMAN RIGHT TO HEALTH

Jonathan Wolff

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

To my brothers: Rick, Dave, and Ben.

CONTENTS

Introduction

THE HUMAN RIGHT

TO HEALTH DILEMMA

B ooks on global health often start with a nasty shock: a disturbing detailed example, or bare statistics presented with a pretense of scientific objectivity. Take the following, unearthed by the Nobel Prize-winning development economist and political philosopher Amartya Sen, in a foreword to the wonderful book Pathologies of Power by medical doctor and anthropologist Paul Farmer, about whom we will be hearing more later. In 1990 the median age at death in sub-Saharan Africa was just five years, which is to say that the number of infants and young children who died before reaching the age of five was the same as the number of deaths of everyone who survived beyond five years.

Very high levels of infant mortality were once a fact of life (if that is the way to put it) everywhere in the world, but they have not been seen for generations in those established market economies. Decent food and housing, as well as modern hygiene and sanitation remove many of the threats to infant health. The assistance of skilled midwives and doctors in birth shrink newborn mortality. And a range of medical techniques, from advanced surgery to simple powders to overcome diarrheal dehydration, can make a huge difference to survival in childhood. We do not need to make new medical discoveries or invent new vaccines or pharmaceuticals to prevent the great majority of the worlds infant deathsor adult deaths, for that matter. So it may seem as obvious as anything that the world community has the moral duty to take action. But what sort of duty is this? And conversely, what sorts of moral claims does each individual have to a full life in good health?

Many theorists and activists now argue that there is a human right to health, and that the early death and recurrent illness of so many millions of people show that this right is being violated on a vast scale. But of course, the claim that there is a human right to health raises a whole host of further questions. Is there really a right to health? What does this actually mean? What does it call for in practice? Even those with good answers to the theoretical questions may feel daunted by the practical issues. Providing essential medical care and keeping people free from disease by providing nutrition, clean water, sanitation, and decent working and housing conditions may not seem much to ask, until we start to think about the cost and who should pay it. General programs to protect people from environmental threats to health and for universal advanced medical care are simply beyond the resources of many, perhaps most, of the countries of the world. Claiming that there is a universal human right to health can seem naive. It is, according to some commentators, utterly unrealistic, even close to dishonest. It has also been argued to be disastrous, diverting countries from systematic, cost-effective, investment in health systems, devoting funds to those who shout the loudest. But the main difficulty is this: how can there be a human right to health if the resources are just not there to satisfy it?

That dilemma is the subject of this book. On the one hand, the reasons for asserting a human right to health seem overwhelming. On the other, a universal human right to health seems impossible to satisfy in the current conditions of the world. Some theorists consequently reject the idea of a human right to health, arguing that we need to approach global health issues in a more pragmatic fashion. Others, more idealistic, have held fast to the idea of a human right to health, arguing that it is too important and basic to be surrendered. Their task is then to work out how to make the human right to health realistic. This book will be an exercise in cautious idealism.

Chapter 1

THE UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS

BACKGROUND

B eing imprisoned for a lengthy period without trial, everyone would agree, is a violation of human rights. But it would be a joke, and not a very funny one, to assert that your rights had been violated by several months of unexpected foul weather. Is suffering from ill health more like wrongful imprisonment, or more like an inhospitable climate? After all, falling ill is generally assumed to be a matter simply of bad luck, unless, as it often is, it is a result of your own lifestyle choices.

But consider Moleen Mudimu, who died of AIDS in Zimbabwe in 2006. For the last year of her life she suffered terribly; her flesh wasted away, and her body was covered with sores and fungal infections. The anti-retroviral drugs that would have restored her to a decent level of fitness and significantly prolonged her life were available in the pharmacy at the end of her road. But she was unemployed and had no money to buy them. In any case, purchasing power had been destroyed by the hyperinflation that has been a feature of President Mugabes chaotic rule. Zimbabwes previously well-functioning health system had collapsed, and although free treatment was available to a few, demand greatly outstripped supply. So she died. Whatever the cause of her condition, it seems perfectly reasonable to say that Moleen Mudimus human right to health was violated.

To say this much is to make a moral claim. But it is a claim that is also supported in international law. Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) begins:

The States parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

This covenant, which came into force in 1976, was a way of giving effect to some of the rights set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of 1948, Article 25(1) of which acknowledges a right to medical care.

Next page