Aleks Sierz FRSA is Visiting Professor at Rose Bruford College, and author of In-Yer-Face Theatre: British Drama Today (Faber, 2001), The Theatre of Martin Crimp (Methuen Drama, 2006), John Osbornes Look Back in Anger (Continuum, 2008) and most recently Rewriting the Nation: British Theatre Today (Methuen Drama, 2011). He also works as a journalist, broadcaster, lecturer and theatre critic.

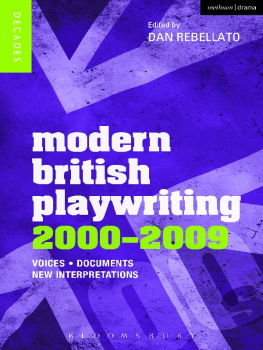

MODERN BRITISH PLAYWRITING: THE 1990s

VOICES, DOCUMENTS, NEW INTERPRETATIONS

Aleks Sierz

Series Editors: Richard Boon and Philip Roberts

CONTENTS

by series editors Richard Boon and Philip Roberts

This book is one of a series of six volumes which seek to characterise the nature of modern British playwriting from the 1950s to the end of the first decade of this new century. The work of these six decades is comparable in its range, experimentation and achievement only to the drama of the Elizabethan and Jacobean dramatists. The series chronicles its flowering and development.

Each volume addresses the work of four representative dramatists (five in the 20002009 volume) by focusing on key works and by placing that work in a detailed contextual account of the theatrical, social, political and cultural climate of the era.

The series revisits each decade from the perspective of the twenty-first century. We recognise that there is an inevitable danger of imposing a spurious neatness on its subject. So while each book focuses squarely on the particular decade and its representative authors, we have been careful to ensure that some account is given of relevant material from earlier years and, where relevant, of subsequent developments. And while the intentions and organisation of each volume are essentially the same, we have also allowed for flexibility, the better to allow both for the particular demands of the subject and the particular approach of our author/editors.

It is also the case, of course, that differences of historical perspective across the series influence the nature of the books. For student readers, the difference at its most extreme is between a present they daily inhabit and feel they know intimately and a decade (the 1950s) in which their parents or even grandparents might have been born; between a time of seemingly unlimited consumer choice and one which began with post-war food rationing still in place. Further, a playwright who began work in the late 1960s (David Hare, say) has a far bigger body of work and associated scholarship than one whose emergence has come within the last decade or so (debbie tucker green, for example). A glance at the Bibliographies for the earliest and latest volumes quickly reveals huge differences in the range of secondary material available to our authors and to our readers. This inevitably means that the later volumes allow a greater space to their contributing essayists for original research and scholarship, but we have also actively encouraged revisionist perspectives new looks on the older guard in earlier books.

So while each book can and does stand alone, the series as a whole offers as coherent and comprehensive a view of the whole era as possible.

Throughout, we have had in mind two chief objectives. We have made accessible information and ideas that will enable todays students of theatre to acquaint themselves with the nature of the world inhabited by the playwrights of the last sixty years; and we offer new, original and often surprising perspectives on both established and developing dramatists.

Richard Boon and Philip Roberts

Series Editors

September 2011

Richard Boon is Professor of Drama and Director of Research at the University of Hull

Philip Roberts is Emeritus Professor of Drama and Theatre Studies at the University of Leeds

My main thanks goes to my partner Lia Ghilardi, who helped me at every stage of this book. I would also like to thank the series editors, Richard Boon and Philip Roberts, for their original vision, professional guidance and excellent advice. Likewise, I am extremely grateful for all kinds of help to my publisher Mark Dudgeon at Methuen Drama, and to the members of his staff: especially Ross Fulton, Charlotte Loveridge, Helen Flood, Chris Parker and Neil Dowden. My guest contributors Catherine Rees, Trish Reid and Graham Saunders delivered their superb chapters on time, and responded to my editorial suggestions with unfailing good humour. Especially helpful in assembling the Documents section was my fellow series author Dan Rebellato, and grateful thanks should also go to Simon Kane, Mel Kenyon, Anthony Neilson, Mark Ravenhill and Philip Ridley. I am also indebted to Cath Badham, Michael Blyth, Keith Bruce, David Greig, Sarah Jane Marr and Simon Trussler. Thanks guys!

Aleks Sierz, London, July 2011

Nastasja One day. Ill tell you the story of my life. Ill write it for a play and theyll make it into a worldwide film.

David Greig, The Cosmonauts Last Message to the Woman

He Once Loved in the Former Soviet Union, 1999

At the start of Jonathan Coes novel The Rotters Club, two young people, Sophie and Patrick, meet in a restaurant, and she asks him to imagine how different the past is. For her, Britain in the 1970s was:

Completely different. Just think of it! A world without mobiles or videos or Playstations or even faxes. A world that had never heard of Princess Diana or Tony Blair, never thought for a moment of going to war in Kosovo or Afghanistan. There were only three television channels in those days Patrick. Three! And the unions were so powerful that, if they wanted to, they could close one of them down for a whole night. Sometimes people even had to do without electricity. Imagine!

Although it is easier to imagine the 1990s than the 1970s, todays Sophies and Patricks might also find it strange to imagine a world without the iPhone, iPod, Facebook, Twitter, Skype, Wikipedia, Kindle, Nintendo DS, audio downloads or MacBook Air laptop. At the very start of the decade, the digital revolution was nowhere to be seen, the driving forces behind Britpop (Noel Gallagher or Damon Albarn) were unknown teenagers and British theatre was seen as in crisis. In global terms, the terrible genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia hadnt yet happened, China was not yet a major economic player and Saddam Hussein seemed containable; very few people had heard of Osama bin Laden. In British politics, John Major was prime minister, Tony Blair was a minor politician and New Labour hadnt been invented yet. David Cameron was still working as a junior researcher in the Conservative Research Department after leaving Oxford University. Other, less privileged, students didnt have to pay tuition fees. So the 1990s are already something of a foreign country, whose inhabitants did things differently.

Family life

The traditional family is dead, killed off by cohabitation and divorce.

- In 1999, only about 200,000 first marriages take place in the UK, with average age at first marriage twenty-eight for women and thirty for men. Cohabitation increases, with 1.5 million or 15 per cent of all couples cohabiting. Unmarried motherhood rockets, with the highest rate in Europe of children born outside marriage.

- 73 per cent of households are composed of heterosexual couples (1996).