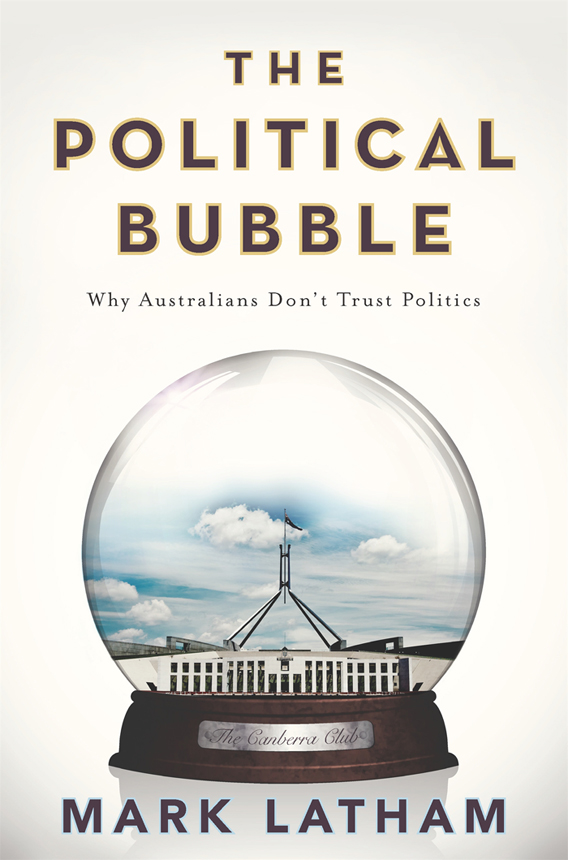

AboutThe Political Bubble: Why Australians Dont Trust Politics

Australians once trusted the democratic process.

While we got on with our lives, we assumed our politicians had our best interests at heart.

Not anymore. That trust has collapsed.

Mark Latham joined the Labor Party in the late 1970s hoping to improve peoples lives through parliamentary service. Twenty-five years later, the Opposition Leader ended up as disillusioned as the rest of us. The scorching honesty of The Latham Diaries ensured hed burned his political bridges, but ostracism from the Canberra Club has its advantages.

In The Political Bubble Mark Latham is free to explore how parliamentary democracy has lost touch with the people its supposed to represent. As with most institutions at risk, politics has become more tribal, with left- and right-wing fanatics dominating formerly robust, mainstream parties.

After the disappointment of the Rudd/Gillard years, Tony Abbott promised to restore trust in Australian politics but, as with most of his promises, it didnt happen. The Political Bubble looks at the new governments policies how Abbott is adding to distrust, not solving the problem.

What can be done about this democratic deficit? Can our parliamentary system realign itself with community expectations or has politics become one long race to the bottom?

Contents

To Janine Lacy and our three children, Oliver, Isaac and Siena Latham

Introduction

Like most Australians born in the 1960s, I grew up trusting in public institutions. In my family we didnt always agree with the decisions they made or endorse every individual decision-maker, but on balance, we thought they were doing their best to advance societys interests. Even when errors were made, there was genuine hope for better outcomes next time. The twin emotions of trust and hope worked together.

In effect, we delegated part of our citizenship to powerful people elsewhere, expecting them to do the right thing on our behalf. How could it be otherwise? We lived in a fibro home in a public housing estate in Sydneys western suburbs. Until I got to Sydney University in 1979, no one on either side of the family had been past high school. Even if my parents and grandparents had wanted to get involved in public life, they lacked confidence in their understanding of issues and political decision-making. If pushed to participate, they would have said they werent well-educated enough.

Across the family, robust opinions were expressed about politics and current affairs, but no one felt sufficiently self-assured to take these views into the public arena. Public life was seen as a different world, best left to those with better qualifications and speaking skills. We practised the Australian habit of cynicism about powerful individuals, often expressed through dry larrikin humour, but only ever in private. This approach was balanced by a strong residual faith in the system of government. We might not have liked every politician (my maternal grandfather, for instance, was very critical of Bob Menzies), but we liked the idea of democracy and party politics. If we couldnt actively participate in public forums, it was reassuring to know that the system would produce others who could.

This was a common outlook in Australia 50 years ago. People grew up preparing to work in the same jobs and live in the same suburbs as their parents and grandparents. Expectations of economic mobility were low. For this generation of citizens, trust in public institutions was a substitute for political activity and workplace agitation. Other, better credentialed people were expected to make the big calls and get on with running the country.

Thus society functioned by an unwritten compact: working people would live relatively simple lives, undisturbed by feelings of disillusionment and protest, so long as the major organisations around them discharged their duties effectively. Political passivity meant that the working class had no choice but to delegate power to trusted authorities. I found out at university that this is what neo-Marxists called hegemony the perpetuation of social order. Less pretentiously, in our national conversation, it goes by the phrase shell be right.

This book is about the collapse of trust and hope in Australian politics. It charts the way in which, over the past 20 years, the major political parties have broken the social compact and discredited themselves in the eyes of the electorate. Things are not right in the parliamentary system. A Monash University survey in October 2013 found that only 3 per cent of Australians had a lot of trust in political parties, while the corresponding figure for Federal Parliament was 7 per cent. Those inclined to trust the Federal Government fell from 48 per cent in 2009 to 27 per cent, with just 4 per cent of people saying they almost always trusted the administration in Canberra.

These statistics are supported by anecdotal evidence. In my local community in south-west Sydney, people often come up to me wanting to talk about politics. Rarely do they express faith in the system or optimism that either of the major parties is acting in their interests. Theyre not just having a whinge. It reflects a fundamental change in belief. Citizens are better educated and more confident in their views, more inclined to challenge the political system and its shortcomings. The passive delegation of authority to ruling elites has been broken.

What was once seen as a credible form of governance entrusting others to make important decisions on our behalf is now seen as illegitimate. The notion of democracy as a force for good has been lost, replaced by a new, adversarial way of looking at parliamentary politics. Whereas for much of the last century, people thought the system of government was on their side, they now think it is working against them. Class struggle still exists, not in the workplace, but in the popular perception that Australias political class is undermining the public interest. The famous formulation of government of the people, by the people, for the people has been replaced by government versus the people.

* * *

While undoubtedly the turbulence of the Rudd/Gillard era has added to the level of disillusionment, the problem runs deeper than the work of one party or one parliament. It goes beyond the contingencies of minority and majority governments. The electorate has given up on both sides of politics a crisis in democratic faith. This can be seen in the publics reaction to the change of government in September 2013. No sooner had the Australian people elected a new prime minister in Tony Abbott, who for three years had insisted he would rebuild popular trust in politics, than they realised they had put a rorter in the role.

Abbott could not be trusted to use his taxpayer-funded travel entitlements properly, having claimed for attending wedding receptions and

He even defended a proven rorter in Don Randall, the Western Australian Liberal MP who misused his entitlements in travelling to Cairns to purchase an investment property. The thud of collapsed public expectations could be heard around the country. People had been watching the first steps of the new government to see if, as Abbott had consistently promised, things would be different this time. Instead, the prime minister associated himself with the worst features of the old system. He defined his administration as no less self-serving and self-absorbed than the thousands of MPs before him whom the electorate had grown to distrust.