When I began writing Money-Driven Medicine, my goal was to tell the story of health care in America through the eyes of the doctors, patients, hospital administrators, health care executives, economists, and Wall Street analysts who understand firsthand the messy realities of a marketplace where money drives medicine.

This meant relying on the generosity of countless strangersvery busy strangerswho, over the past two-and-a-half years, have agreed to share their time, their stories, and their insights.

In particular, I want to thank Liz Dreesen, Bruce Vladeck, Lynn Schnurnberger, Lazar Greenfield, Ed Dench, Charles Rosen, Gerard Anderson, Lawrence Casalino, John Wennberg, Elliott Fisher, Thomas Riles, Robert Rosen, Donald Lefkowits, Diane Meier, George Lundberg, Kenneth Kizer, Mark McDougle, George Halvorson, Robert Califf, James Robinson, Thomas Rice, Andrew Weisenthal, Jay Crosson, Kim Adcock, Jack Mahoney, David Polly, Jonathan Skinner, Lisa Schwartz, Steve Woloshin, Bill Weeks, Sheryl Skolnick, Richard Evans, Neil Calman, Steffie Woolhandler, Jim Moriarty, Steven Hunt, Tony Ginocchio, Bob Wooten, John Cherf, George Cipolletti, Peter Gross, Bradford Gray, Patrick Malone, Arthur Kellerman, Genie Kleinerman, Katherine Baicker, Amitabh Chandra, Kenneth Thorpe, Jeff Villwock, Scott Wallace, Barry Hieb, J. B. Silvers, Joan Richardson, John Stobo, Karen Sexon, Ben Brouhard, Vindell Washington, John Harold, Sid Abrams, Joanne Andiorio, Clifford Hewitt, Evan Melhado, James Orlikoff, Roger Hughes, Kenneth Cohen, Kenneth Wing, Deborah Weymouth, and Dugan Barr. Without them, this book would not exist.

In addition, I owe thanks to the journalists who graciously shared their sources and their knowledge, including Susan Dentzer, Tom Linden, Melissa Davis, Steve Twedt, and Joanne Kaufman. These are only a few of the outstanding writers and reporters who have contributed their ideas and stories to this book; I have tried to acknowledge their help throughout, both in the footnotes and in the text.

Special thanks go to those who have offered comments on all or part of the manuscript. In particular, I want to single out Larry Martz, a superb editor who can remove two words from a sentence and make it instantly better, and Michael Klotz, who read the entire manuscript twice, questioning contradictions, flagging infelicitous phrases, all the time refusing to be rushed. (No, waittheres a better way to put this.) The fact that he is my son makes his patience all the more extraordinary. As I raced toward a final deadline, Elizabeth Woodman and Maureen Quilligan also offered much-needed encouragement and counsel.

Anne Greenberg, who copyedited the manuscript, did a meticulous job, not only copyediting but fact-checking hundreds of names and details. Any errors that remain are mine and mine alone. Meanwhile, Alex Scordelis, the editorial assistant who worked on the project, smoothed the path to production without letting me feel the bumps along the way.

Finally, I want to thank my editor, Marion Maneker, who believed in this book from the very beginning. His unflagging enthusiasm and confidence made the hard work of writing much, much easier.

As the 21st century began, health care seemed to slide off the list of national priorities. And no wonder. The horror of the World Trade Center and Pentagon bombings, the continuing threat of global terrorism, the terrible realities of the war in Iraq, and the uncertainties of a post-bubble economy consumed the nations attention.

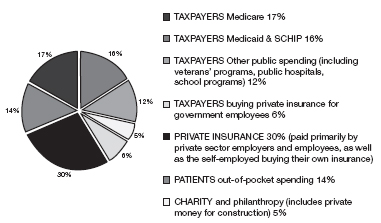

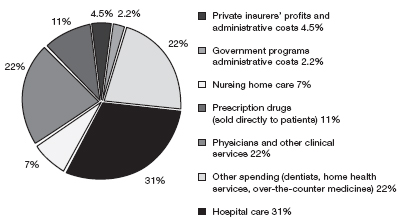

Yet, beneath the headlines, and without much public discussion, a national health care crisis continues to brew. As costs balloon, more and more of the nations resources are devoted to medical care. In 1970 health care spending represented just 7.1 percent of gross domestic product. By 2005, the nations health care bill equaled more than 16 percent of everything that the economy produced. And in 2020, PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Research Institute projects health care spending will gobble up 21 percent of the pie.

If medical costs continue to outstrip economic growth, eventually there will be no money left for anything elseeducation, defense, housing, the arts. Well all just be operating on each other, one Wall Street observer notes wryly. Health care will swallow GDP.

Of course what cant happen, wont. For one, U.S. workers and employers simply cannot afford health insurance premiums that in recent years have been rising four times faster than wages.

Already, more and more middle-class Americans find themselves priced out of the health care market. Since 2000 the cost of health insurance has spiraled by 73 percent.

Even for the relatively affluent, health insurance is fast becoming a luxury. In 2005 the average annual premium for a family policy stood at an astounding $10,880close to one-quarter of median annual income before taxes.

And it is not only the uninsured who are vulnerable to being blindsided by the levitating cost of essential care. These days, more and more families who think they are covered are discovering that the blanket is short. They may not be uninsured, but they are underinsured. Thanks to rising deductibles, hefty co-pays, and caps on total reimbursements, some patients diagnosed with a chronic illness are finding that they cannot afford to fill all of the prescriptions that their doctor gives them. Others realizetoo latethat when ICU care for a child with cancer costs $49,000 a day, a family can exceed a million-dollar cap on coverage in a matter of months.