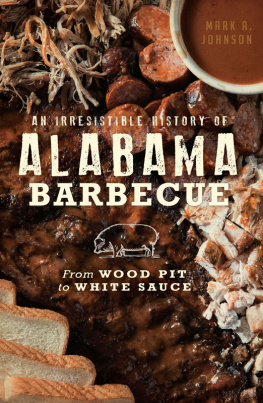

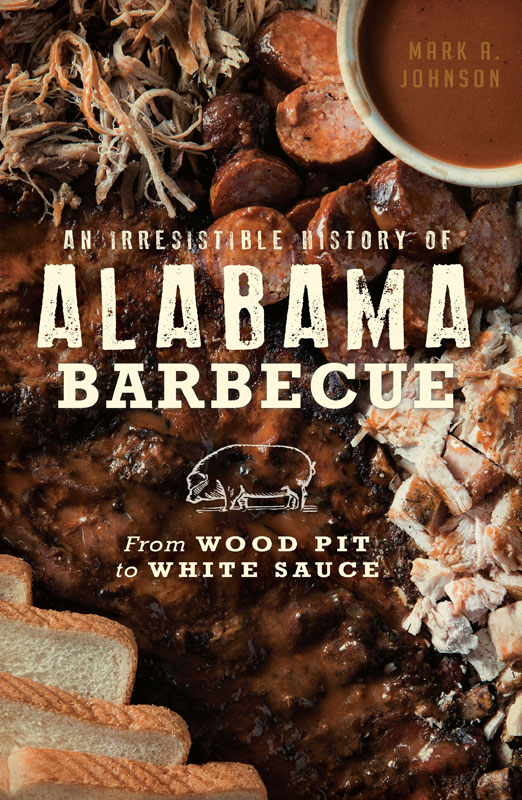

Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by Mark A. Johnson

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43966.212.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017938334

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.702.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

I dedicate this book to my wife, Kate, who introduced me to Alabama white sauce and supported me in the publication of this book.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am thankful for numerous people who have helped me with this book. I am particularly grateful to the Southern Foodways Alliance, especially John T. Edge, and the Alabama Tourism Department. They provided me the opportunity to study Alabama barbecue. I could not have done this project without the oral histories conducted and archived by the Southern Foodways Alliance.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Joshua Rothman. With the grant funded by the Southern Foodways Alliance, he hired me to produce the now-entitled essay Pork Ribs and Politics: The Origins of Alabama Barbecue. I would never have approached barbecue from a historical perspective if not for his choosing me. I could never have completed the project without his assistance and encouragement. In the process of writing the article, I received help from many people, especially at the University of Alabama, including Dana Alsen and Megan Bever.

In the process of turning the original article into a book-length project, I encountered many helpful people and their scholarship. I benefited from the work of many scholars, especially Angela Cooley, who helped me take my first steps into food history. I owe much of my initial understanding of the subject of barbecue to the work of historians Robert F. Moss and Valerie Pope Burnes. In my own work, I have attempted to live up to the standards set by these scholars. I have blended their work with my own research to trace major historical developments with specific attention to Alabamas unique people and places.

During the research phase of producing this book, I accumulated many debts. I would like to thank the many restaurateurs who spent time sharing their stories and feeding me. I hope I have done justice to your hard work. I would also like to thank the staff at the Center for the Study of the Black Belt at the University of West Alabama. They helped me find archival material related to this project.

Finally, I am grateful to the support of family and friends. First, I would like to thank my parents, who taught me to love history and how to work hard. Next, I would like to thank Pat and Melissa, who gave me the nickname Dr. BBQ. I could not have completed this project without the love and support of my wife, Kate, to whom I dedicate this book.

INTRODUCTION

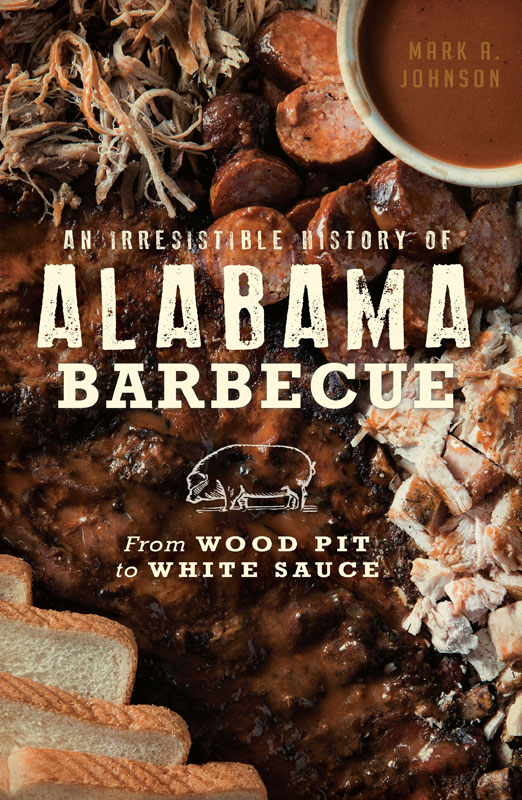

Alabama barbecue serves as a source of state pride. Nationally, Memphis, North Carolina, St. Louis and Texas get the publicity. In restaurants and backyards across the state, Alabamians boast about the states barbecue. They have put their own barbecue up against the food from any of these other places. In these contests, they have had their fair share of victories.

Within the state, however, Alabamians do not even agree about how to define Alabama barbecue. In the Tennessee River Valley, barbecue means chicken with white sauce. In Birmingham, barbecue entails pork on a sandwich with a tomato-based sauce and a couple pickles. In Tuscaloosa, barbecue consists of ribs basted with a spicy vinegar-based sauce. These generalizations still do not adequately describe Alabama barbecue. In the Tennessee River Valley, for example, customers can also find mustard-based hotslaw at many of the local restaurants, especially in the Shoals.

If barbecue does not have a defining ingredient or flavor profile, it does have a unique story. In Alabama, barbecue transcends race, class and generational boundaries and relies on a multi-racial and multi-ethnic restaurant-based scene emphasizing open pits and hickory wood.

From the beginning, Alabama barbecue did not necessarily have these characteristics. Instead, they developed over time. These defining elements of Alabama barbecue have evolved over the past four hundred years, with roots in the Columbian Exchange, slavery and emancipation, Jim Crow and civil rights and the rise of the restaurant industry. In each phase of development, Alabama barbecue attained some of its present-day characteristics. This is the story I tell in this book.

Throughout the book, I weave many stories together. On the national level, historic events shaped how people produced and consumed food, including barbecue. In Barbecue: The History of an American Institution, historian Robert F. Moss explains these developments and their affect on barbecue across the nation. I could not have produced this history of Alabama barbecue without Mosss path-breaking work. In this book, I have told a story about how national and local events played out in Alabama, affected the restaurant industry and, therefore, influenced barbecue in the state.

In this book, I refer to barbecue as a food, a cooking technique and a social event. As a food, Alabama barbecue consists of many different types of meat, sauces and preparation methods. I have used the term to describe all of them.

Finally, I want to emphasize that people from numerous ethnic and racial groups made their own contributions to Alabama barbecue. In fact, present-day barbecue could not exist without the blending of techniques, recipes, ingredients and labor from Native Americans, Africans and Europeans. So the story of Alabama barbecue begins at the point of contact between these groups of people, long before Alabama, as an entity, even existed.

CHAPTER 1

A DELICIOUS FLAVOR IN NO OTHER MANNER OBTAINABLE

The Origins of Alabama Barbecue, 14921800

In the 1000s, the Norse Vikings colonized northern North America, in present-day Newfoundland. Although their settlement of LAnse aux Meadows did not last long, Vikings continued to visit the area to fish and hunt whales. Frequently, they came ashore to process their catch but also to trade with Native Americans. In 1492, Christopher Columbus and his crew arrived in the Caribbean. In 1493, Columbus returned with a massive fleet to commence the Spanish colonization of the Caribbean.

When Europeans made landfall in the Americas, they brought with them people, plants and diseases previously unknown to the Native Americans. Likewise, the Europeans discovered things native to the Americas that Europeans had never known. Europeans and Native Americans coveted one anothers strange things, so they traded. This process, called the Columbian Exchange, forever changed the world.

The Columbian Exchange revolutionized cuisine around the world. Before the Columbian Exchange, Italians did not have tomatoes. The Irish did not have potatoes. Europeans brought these items, and many more, back with them from the Americas. Similarly, Native Americans did not have beef or pork until Europeans brought them. Native Americans did not have coffee either. They also did not have wheat or rice. Native Americans had chocolate, but Europeans had sugar. Without the Columbian Exchange, therefore, the modern chocolate bar could not exist. The Columbian Exchange made modern-day cuisine possible, especially barbecue.

Next page