OPEN COURT and the above logo are registered in the U.S.

Patent and Trademark Office.

1992 by Open Court Publishing Company

First printing 1992

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Open Court Publishing Company, La Salle, Illinois 61301

The photograph used in the cover design is reproduced by permission of the Ullstein Fotoarchiv. It shows socialists in Berlin in 1918 demonstrating for All Power to the Workers and Soldiers Councils.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Steele, David Ramsay.

From Marx to Mises : post-capitalist society and the challenge of economic calculation / David Ramsay Steele.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8126-9862-6

1. Von Mises, Ludwig, 18811973. 2. Marx, Karl, 18181883. 3. EconomicsHistory. 4. CapitalismHistory. 5. Post-communism.

I. Title.

HB101.V66S73 1992

330.9dc20

92-35738

CIP

For Lisa

BRIEF TABLE OF CONTENTS

DETAILED TABLE OF CONTENTS

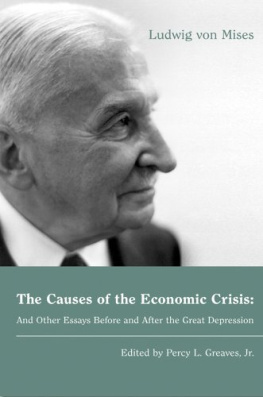

Karl Marx (18181883) and Ludwig von Mises (18811973) were economists of Jewish background, born and raised in German-speaking communities, who each resided for the final 33 years of their lives in the English-speaking world. At the times of their deaths, they each had a loyal and growing following but were outsiders, voices crying in the wilderness. After their deaths, the influence of their ideas began to spread with increasing rapidity.

Marx and Mises took the prevailing economic doctrines of their day, and developed these ideas in new ways, giving their own theories a distinctive cast which mainstream thinkers found unacceptable. In the final decade or so of their lives, they both tended to repeat their earlier views without fresh thinking, and seemed to be out of touch with contemporaneous discussions.

Marx and Mises combined erudition with a combative, frequently vituperative style of presentation, displaying in their writings little patience with critics. They presented economic theory as part of a much larger theoretical panorama, and advanced peculiar views on history and human behavior. They each became committed to unpopular political doctrines at a time when these doctrines were despised by conventional people, and therefore costly to embrace. They both helped to rescue their political causes from this pariah status, though in each case we can see with hindsight that those causes were already on the rise, a rise from which the posthumous reputations of Marx and Mises benefitted. They each attracted a small, industrious band of dedicated disciples prepared to braveand reciprocatethe disdain of conventional thinkers.

As men and as thinkers, Marx and Mises could hardly have been more different. But a confrontation of their entire theoretical systems is far from being the purpose of this book. Rather, I am concerned to look at an argument, advanced by Mises against Marxism and other forms of socialism. The argument in question is the economic calculation argument, which I will often refer to as the Mises argument, deployed by Mises to support his seemingly preposterous claim that socialism is impossible. Misess argument began a vigorous debate, which is still going on in the sense that there is little agreement as to what the outcome was, though most of the essential points had been made by the end of the 1930s.

I try to explain Misess argument from several angles, to give some notion of its historical background and impact, to explore some of the discussions it has provoked, and to look at a few of its broader ramifications. All my historical and theoretical discussions are related directly to my central theme of the Mises argument. For instance, although I examine some of the views of Karl Marx, and although these views are intrinsically fascinating, I dont attempt to present here a balanced picture of Marxs theories, but only an accurate picture of some elements of his thought intimately related to economic calculation. The same goes for Misess theories.

This work is designed to be completely comprehensible to a reader who begins with no knowledge of the economic calculation debate. I take an unorthodox view of some details of that debate, but I explain clearly what the alternative views are. This book can therefore be used as an introduction to the economic calculation issue, but I have taken the discussion a little further here and there. My interest in economic calculation is conceptual or philosophical rather than technical, and I am not attempting to contribute to economic theory.

While I was finishing this book, there occurred the disintegration of the Soviet bloc and the demise of state socialism in Eastern Europe. Almost the only important repercussion for the text was that references to Soviet developments had to be shortened and changed from the future or present tenses to the past tense. This work is concerned with general issues inherent in attempts, usually called socialist, to replace or curtail the market. Although events in Russia have affected the course of the discussion of these issues, viewed from a general theoretical perspective, Soviet experience is only one of many sources of evidence. In all essentials, this book would be the same if the Soviet debacle had been completed in 1921, or if it had been delayed for another 20 years after 1989.

However, Soviet-bloc events may serve to illustrate the importance of this books theme. Across Eastern Europeindeed, across the worldstate planners are putting the ax to state planning; they are encouraging private ownership of the means of production and financial markets such as stock exchanges. Sometimes they hesitate, and tinker with schemes to introduce some fragments of privatization and marketization, hedged about with controls to prevent them functioning as such, but such tinkerers are always in danger of being swept aside by more radical spirits. Practical policy-makers are faced with the apparent fact that, for some reason or other that they cannot fathom, tolerably high living standards for the masses require private property in the means of production, along with substantially free capital and money markets. Meanwhile, there are intellectuals who instruct students in the humanities and convey to successive generations the ruling ideas of this epoch. Overwhelmingly, these intellectuals, whether they consider themselves left or right, are at a loss to give any serious explanation of the Soviet collapse. To them, what has happened still possesses a fairytale qualityand the first legend to congeal was that no one had expected the collapse. This book offers a thread by aid of which such intellectuals may hope to grope their way out of their labyrinth of confusion.

This work is a nonspecialist account of Misess argument. It combines portions of the recognized corpus of economic theory with other considerations which are harder to classify, though perhaps many of them belong to philosophy. The portions of economic theory are elementary, and therefore not especially fascinating to economists, but remain unfamiliar to the typical intelligent, conventionally well-read non-economist. The economist may become exasperated by my belaboring of some fundamentals of economic principles and price theory, intermixed with assertions which he may well regard as more contentious. The non-economist may wrongly suppose that the issues being debated are such as economists have some special competence to judge. But this would be like going to physicists to enquire whether there is a God (In either case one

Next page