To Blythe and Finn

Contents

Carswell Grove

[T]here has been nobody suffered in this matter like I have. I did not do nothing at all to cause that riot.

J OE R UFFIN

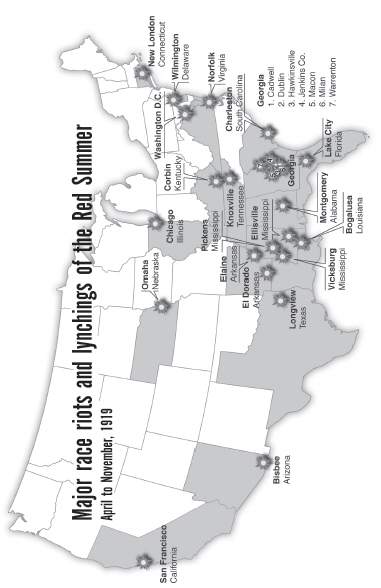

April 13, 1919, was perfect for a celebration. As Joe Ruffin set out to do his morning chores that Sunday, the sky was cloudless and blue. The temperature was in the high 70snormal for spring in east Georgia.

The sixty-year-old man started the day at his barn, rushing to feed his pigs, cows, and horses so he would not be late. He had sent his children ahead to the Carswell Grove Baptist Church in one of the familys two cars, a Buick Six. Ruffin would follow later. The church festival was to mark its fifty-second anniversary. Preachers from several counties were coming to deliver sermons. The choir would give a special performance. More than three thousand people would be on hand for a gala cookout of roast pig and fried chicken. Though Ruffin was not a Carswell Grove member, he had been asked to speak as a prominent black Mason and treasurer of another black church.

Ruffin had lived his entire life amid fields of cotton and sugar cane east of Millen, the seat of Jenkins County. The land he tilled was once part of the plantation

Many of the years had been tough. Several times Ruffin had to mortgage tracts of land. He even took out loans on his mules and horses to cover debts.

He had a large family. The 1910 census recorded three sons and four daughters living with him, plus another son and his family down the road. Ruffin was a widower.

Two sonsJohn Holiday, twenty-six, and Henry, thirteenlived A fourth son, Joe Andrew Ruffin, twenty-four, served with the U.S. Army in France. He was due home in time for the fall harvest.

Whatever Ruffins past struggles, 1919 was shaping up to be profitable. Cotton was fetching extraordinary prices, averaging more than 35 cents per pound, the highest ever. As global demand for cotton increased, futures skyrocketed. This spike was a windfall for Ruffin and millions of other southern farmers from Virginia to Texas.

Jenkins County, Georgia, Many blacks in the county were illiterate, and election records indicate that only a handful were allowed to vote. All county government officials, from commissioners to police, were white.

Most blacks in Jenkins County were sharecroppers renting land from white landlords, but a growing number owned property, a phenomenon occurring all

By the late afternoon of that April 13, however, almost every white man in Jenkins County wanted Joe Ruffin dead.

* * *

Around 11:30 a.m., Ruffins youngest son, Henry, came back to the farm to get his father. famous red clay is sandier in this part of the state and a paler shade of orange. Ruffin could see cultivated land for miles, broken up by copses of loblolly pine and scrub oak as well as thickets of holly and cypress. Hawks and buzzards circled the sky.

Sometime after 2 p.m., Ruffin reached Big Buckhead Church Road, the final road leading to the festival. The dirt road had been around since

Carswell Grove was founded two and a half years after the battle in the midst of the social turmoil caused by the Confederacys collapse. After the war, whites at Big Buckhead Church kicked out blacks, who for generations had sat in segregated pews. Porter W. Carswell, a white judge who owned nearby Bellevue Plantation, gave black congregants two acres of scrubland to erect their own place of worship just down the road. The congregants named their new church in his honor. By 1919, Carswell Grove Baptist Church boasted more than a thousand members, most of them sharecroppers. The yearly celebration of the churchs founding was one of the largest African American gatherings in east Georgia.

As Ruffin drove up the low ridge, he saw throngs of black men, women, and children milling about the grounds. They were talking and laughingit was the cacophony of a large, joyous group. Ruffin parked his car and joined them. After a short time, Ruffin remembered that he had left the door to his house unlocked and decided to drive home. He got in his car, but the swelling crowds blocked the road. He drove as far as he could, almost to Big Buckhead Church, when he was forced to stop and wait for people to move along.

As he sat there, an older Ford drove up behind him and then pulled alongside. People scrambled off the road to get out of the cars way. It stopped abruptly and Ruffin looked over at its occupants: two white lawmen and a distraught black man in handcuffs. Ruffin knew the black man: Edmund Scott, his longtime friend.

Why the two white officers were at the black gathering is unclear. They had no warrant. Marshal Stephens was not even in his jurisdiction. In all likelihood,

L. W. Beach, a white superintendent over black sharecroppers at a nearby plantation, told a different story. Beach was at the festival

Scott, who was driving a minister from another county to the fair, was infuriated by the officers wild driving. Beach heard Scott say, That is the way with some people, they havent got a damn bit of manners. Brown and Stephens then arrested Scott, charging him with possession of an unregistered firearm. They were heading back to the Millen jail with Scott when they passed by Ruffins car and Scott shouted for help. Officer Brown stopped his car and called for Ruffin. Ruffin got out of his car, walked over and stood on the running board of the police car.

What is the trouble with Edmund? Ruffin asked. Officer Brown said they had found a concealed pistol in Scotts car. Beach, positioned about thirty feet away, saw Ruffin take out a checkbook and offer to write a bond check for his friend. The officer told him he needed cash. Ruffin said he could not get that kind of money, $400, on a Sunday. Brown then said, God damn it, I am going to carry him in.

A large crowd immediately gathered around the car, including two of Ruffins sons, Louis and John Holiday. People who were there said Ruffin reached in and tried to pull Scott out. Brown became incensed and shouted, God damn it, get back. He pulled out his pistol and struck Ruffin in the face. The gun went off, hitting Ruffin on the left side of his head, knocking him to the dirt. Ruffin said later he was unconscious for a few minutes. Others said he got up right away.

One person who was there said Louis, Joes oldest son, rushed the car, wrested the gun from Brown and shot the police officer in the head, neck, and body, killing him. Two others said that the father, Joe Ruffin, killed Brown, pulling out his own pistol and firing into the police car. Others said Officer Stephens, a short, heavyset man, stepped out of the car, hunkered down with his pistol drawn. Another round of gunfire erupted. Scott, caught in the middle and handcuffed, was shot to death as he struggled to get out of the way. Stephens was wounded and slumped to the ground.

It was just like a package of poppers [firecrackers], said Ed Tancemore, a white man who saw the shooting, adding that it took no longer than a finger snap. In an instant, Brown and Scott were dead, slumped in the blood-smeared Ford. Stephens lay on the ground, bleeding but conscious. Black men in the crowd attacked him. Some said Ruffins two sons led the assault. Tancemore watched as Stephens was beaten: Every time he would get up, they would knock him back until they got him down the side of the car, and one of them placed his foot in his breast and the other handed him an oak limb, and right there they stopped him.

Next page