Also by M. R. Montgomery

In Search of L.L. Bean

A Field Guide to Airplanes

Saying Goodbye

The Way of the Trout

Many Rivers to Cross

About the Author

M.R. M ONTGOMERY has been a journalist for thirty years and is the author of five other books. He graduated from Stanford University and the University of Oregon with degrees in American history. A native of Montana, he has returned often in search of the landscape and community that make up the last remnants of the days of bison and longhorns, cowboys and schoolmarms. He lives near Boston with his wife, Florence.

February 1803, Washington City

T HOMAS J EFFERSON , third president of the United States, is writing a lengthy letter to William Henry Harrison, military governor of the Northwest Territory; that is, of the scarcely settled lands between the Mid-Atlantic states and the Mississippi River.

Jefferson is his own secretary, and he is almost certainly alone as he writes. The federal government of the United States is very small and highly personal. Jefferson will make a copy of this letter on an unsatisfactory machine called a letterpress that transfers a little of the ink from the original to a flimsy, almost transparent, sheet of paper. The third president is probably sitting in a pair of frayed trousers, wearing house slippers and a coat against the chill. He looks rather more like Bob Cratchit than Ebenezer Scrooge as he instructs Harrison on Indian policy and the role of the western country, across the Mississippi, in managing the Indian problem. We will get to the content of the letter in a moment, but if you are going to understand some of the history about to unfold, it is good to stop a moment and recognize that the entire Executive Office of the President consists of this middle-aged man, wearing casual clothes, alone in a rented house in Washington City.

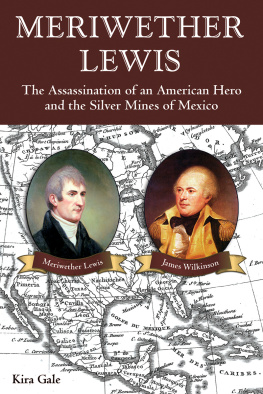

Technically, Jefferson has a personal secretary. This is Captain Meriwether Lewis, U.S. Army, who is about to depart on an exploration of the country west of the Mississippi by ascending the Missouri River to its source and then proceeding down some western river to the Pacific Ocean. Lewis is probably unaware of the contents of the letter. He is a secretary in name only. Jefferson has brought him to Washington to prepare him for a more serious job than copying and filing letters. Lewis expects to lead a clandestine mission through a country that belongs to France, to Napoleon Bonaparte. The government funds for the expedition are a well-kept secret, the result of a concealed congressional vote. And Thomas Jefferson is keeping an important development hidden from the Congress: Two American envoys are about to begin negotiations to buy the island of New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi. Jefferson wants New Orleans so that trade down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers can move freely to the sea from the still lightly settled American soil along the Ohio River and the eastern bank of the Mississippi. It is a few decades before railroads, and goods from Ohio and Kentucky and Mississippi must move on the rivers. The island of New Orleans, first in French, then Spanish, and now again in French hands, is a barrier to free passage.

Napoleon has his little secret, too. Shortly after reacquiring the Louisiana Territory for France (Napoleon is governing Spain with puppets and relatives), Napoleon wants to trade it in for cash. Hes not only ready to sell New Orleans, he wants to dump the whole of Louisianathat is, all of the vast country north of Spanish Mexico and south of British Canada and west of the Mississippi River as far as to the Continental Divide, to the very headwaters of all the western tributaries of the Mississippi. Napoleon is going to need money for more adventuring in Continental Europe, and he is bleeding whole armies into a failing attempt to hang on to Frances Caribbean island colony of Santo Domingo (todays Haiti and Dominican Republic). But Jefferson has no idea that this Louisiana real estate deal is in the works. So, when we read Jeffersons secret addition to his otherwise official letter to Harrison, we must remember that America stops at the Mississippi, with or without the island of New Orleans.

Jefferson begins by telling Harrison that the nations policy is to live in perpetual peace with the Indians, to cultivate an affectionate attachment from them, by everything just and liberal which we can do for them within the bounds of reason. Having said that, Jefferson then instructs Harrison on how to get rid of every last independent Indian tribe between the Atlantic states and the Mississippi.

Harrison is to encourage a series of government trading posts selling at a discount (to undercut the few itinerant French-Canadian traders and the increasing number of British traders coming down from Canada). We shall push our trading... and be glad to see them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop them off by a cession of lands....

Jefferson understands that some recalcitrant Indians may be unwilling to sell and be foolhardy enough to take up the hatchet. In that case, Harrison is to seize the whole country of that tribe and drive them across the Mississippi. This would be an example to others, and a furtherance of our final consolidation.

Jefferson is almost finished. As usual, the letter is in his own hand. And now he draws a firm line of emphasis under his last words. The contents of this letter, he reminds Harrison, must be kept within your own breast, and especially how improper to be understood by the Indians. For their interests and their tranquility it is best they should see only the present age of their history. So, from the very beginning, we see the Indian policy of the United States for what it is: all agreements and all promises are temporary, expedient, and faithless.

There will be times, in the next few years, when almost everyone involved in this business of Louisiana will be happier if they live only in the future age of their history. The wildest plots, the most grandiose dreams, will thrive as long as the actors move toward an imaginary future bliss while ignoring present realities. Only a few will even attempt to judge the practicality of their desired future. They are an odd mixture of schemers, dreamers, revolutionaries, blackguards, and braggarts. Before it is done, Jefferson, that most complicated and opaque personality, will have played more than one of those parts.

April 1803, Harpers Ferry, Virginia

C APTAIN M ERIWETHER L EWIS is at this federal armory on the Potomac River just forty miles upstream from Washington. It is located in Virginia. It will still be in Virginia when John Brown raids the arsenal in October 1859, hoping to raise a slave revolt in the South. West Virginia, now the legal address of the historic armory, is a creature of the Civil War, created in 1863 to carve a free state out of the old rebellious dominion. Lewis is ordering rifles for his expedition up the Missouri River, and by civilian standards they are simple and unremarkable, a shorter version of the Kentucky long rifle, and bored for a heavy, 50-caliber round ball. For the United States government, accustomed to issuing smooth-bore muskets, Lewiss rifles are so unusual and fine that they get their own model number1803.

Next page