CONTENTS

To Gael

PREFACE

A nation, said the French philosopher Ernest Renan, is a people that has done great things together in the past. It is not bound by language or by a common culture but by a shared experience. History is what Canadians have in common.

Canadians believe that their history is short, boring, and irrelevant. They are wrong on all counts. The choices Canadians can make today have been shaped by history. The governors of New France launched arguments that federalists and sovereignists repeat in present-day Quebec. Were the natives who far outnumbered them sovereign allies or enemies or were they subjects of the French king? That debate began early. Early fur traders illustrated economic laws that modern-day resource development unconsciously follows. Canadians trying to understand the challenges of political leadership would do well to take a second look at the arts of Sir John A. Macdonald and William Lyon Mackenzie King.

In each generation, Canadians have had to learn how to live with each other in this big, rich land. It has never been easy. If we ignore history, we make it doubly difficult. This book has been written to make it a little easier for Canadians to know and understand their country. It is concerned with politics and economics as well as how Canadians have lived their own lives, because our greatest problems and achievements have come through the entwining of our lives with a community.

This book was first written with the inspiration and support of Mel Hurtig. That inspiration was reinforced unconsciously and perhaps grudgingly by generations of students at Erindale College, the Mississauga campus of the University of Toronto. Many were new Canadians, committed to an adopted country, yet puzzled by it and reluctant to take its truths for granted. Because of the enriching flow of new Canadians, there will never be a final history of Canada.

Later, at McGill University in Montreal, students were diverse in a different way. McGill students reflect all of Canada, from Newfoundland to the Lower Mainland of B. C. Many are francophones, and I seldom encountered a class without articulate sovereignists. Some were students from Europe or Asia. I couldnt have designed a better forum to understand Canada and its wonderful complexity.

More than most of my books, this one profited from the perceptiveness and patience of my original editor, Sarah Reid, of my current editor, Alex Schultz, and of my late wife, Jan. They deserve whatever claims the book may have to be readable. Where it fails, they could not prevail over stubbornness. Clara Stewart, Kathie Hill, and Lorna Wreford have laboured on this manuscript at various stages, reminding me that readers deserve clarity as well as facts. The latest edition, the first full revision since 1983, has involved my beloved wife and partner, Gael Eakin. Perhaps only the partners of other authors will have any idea of what she has endured. Meanwhile, Suzanne Aubin and Marie-Louise Moreau have added their wisdom and experience of Canada, protected my time, and absorbed my burdens so that this work could be done. I hope they all accept a share of what is good in the book.

Any new edition of a book is better than its predecessor, if only because colleagues and reviewers have generously suggested corrections and improvements. I particularly benefited from the erudition of Vincent Eriksson of Canmore Lutheran College. Neither he nor the many others bear any responsibility for errors, misinterpretations, and what the Anglican Book of Common Prayer calls invincible ignorance.

This book is a product of its birthplace, a suburban campus in the young city of Mississauga, a place as full of energy as it is of self-doubt. It has been renewed in Montreal, among people passionately committed to a new, sovereign Quebec and others as passionately devoted to the preservation of a tolerant, multi-cultural Canada. The wisdom of Oliva Dickason and Gerald Alfred has reminded me often of the two-row wampum as a symbol of our historical sharing with the First Nations of this continent. Whatever our future, we should understand how Canada has travelled through its most recent centuries to the present. If we follow that voyage, our history will give us confidence in change and compromise and in some enduring truths about communities and families and human beings. It should also tell us that no ideas, however deeply held, last forever.

Montreal, Quebec

April 24, 2006

NEW NATION

NEW NATION

A t midnight on July 1, 1867, church bells rang out from Lunenburg to Sarnia. In Ottawa, militia artillery fired the first round of a hundred-gun salute. Crowds cheered the explosions and waited as the militiamen laboured in the dark with rammers and sponges. At dawn, 4 million people awoke as citizens of a new Dominion of Canada. Some of them, in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, might resent their fate, but a two-day weekend (for July 1 fell on a Monday) was too rare a treat to be shunned. Picnics, lacrosse tournaments, cricket matches, and excursions focused the days excitement. Farm families united around groaning kitchen tables. On Torontos waterfront, a huge ox was roasted all day so that dripping hunks of meat could be distributed to the poor.

Carefully respecting the ban on Sabbath labour, George Brown arrived at the offices of his Globe at midnight, determined to do editorial justice to events he had helped to bring about. As the morning hours passed, his pen filled page after page with statistics, politics, history, business, and hope for the new Dominion. Only at dawn was Brown finished. Solemnly he pledged that the teeming millions who shall populate the northern part of this continent, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, shall, under a wise and just Government, reap the fruit of well-directed enterprise, honest industry and religious principles. By then, the express trains that normally carried the Globe to readers across the old province of Canada West had departed without it. Browns aspirations for Canada would go largely unread.

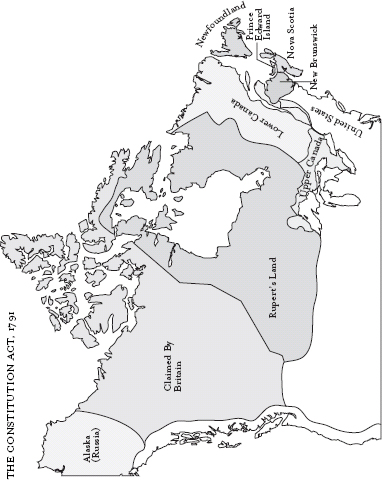

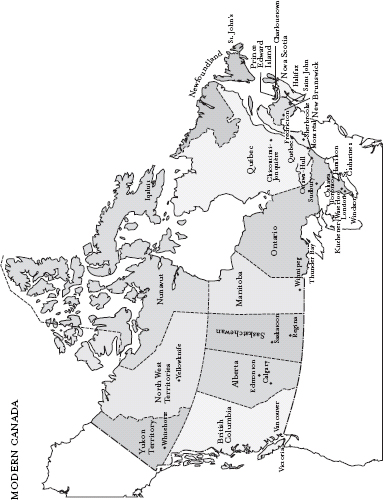

In the summer of 1867, Canada was little more than hopes. Confederation covered only 370,045 square miles (958 416.5 km2), a mere tenth of British North America. Three colonies had become four provinces, but the northern edge of the new provinces of Ontario and Quebec ran vaguely along the water-shed that drained into the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes. The population 3,816,680 by official count in 1871 was a tenth as large as that of the bustling, powerful nation to the south. Many Canadians wondered how long they would survive the American boast that manifest destiny would allow them to rule the entire continent.

George Browns Dominion Day mood allowed no dismay. Small as it was, Canadas population was at least as large as Americas had been when the Thirteen Colonies won their independence in 1783. Confederation itself was proof that the divisions between a million French Canadians and two and a quarter million Canadians of British origin could be overcome. If there remained differences of race, region, and religion, prosperity would dissolve them. The