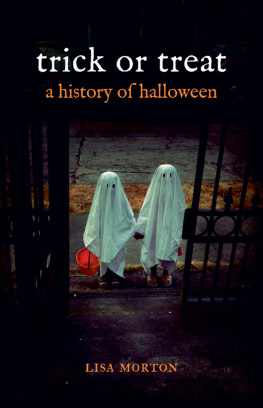

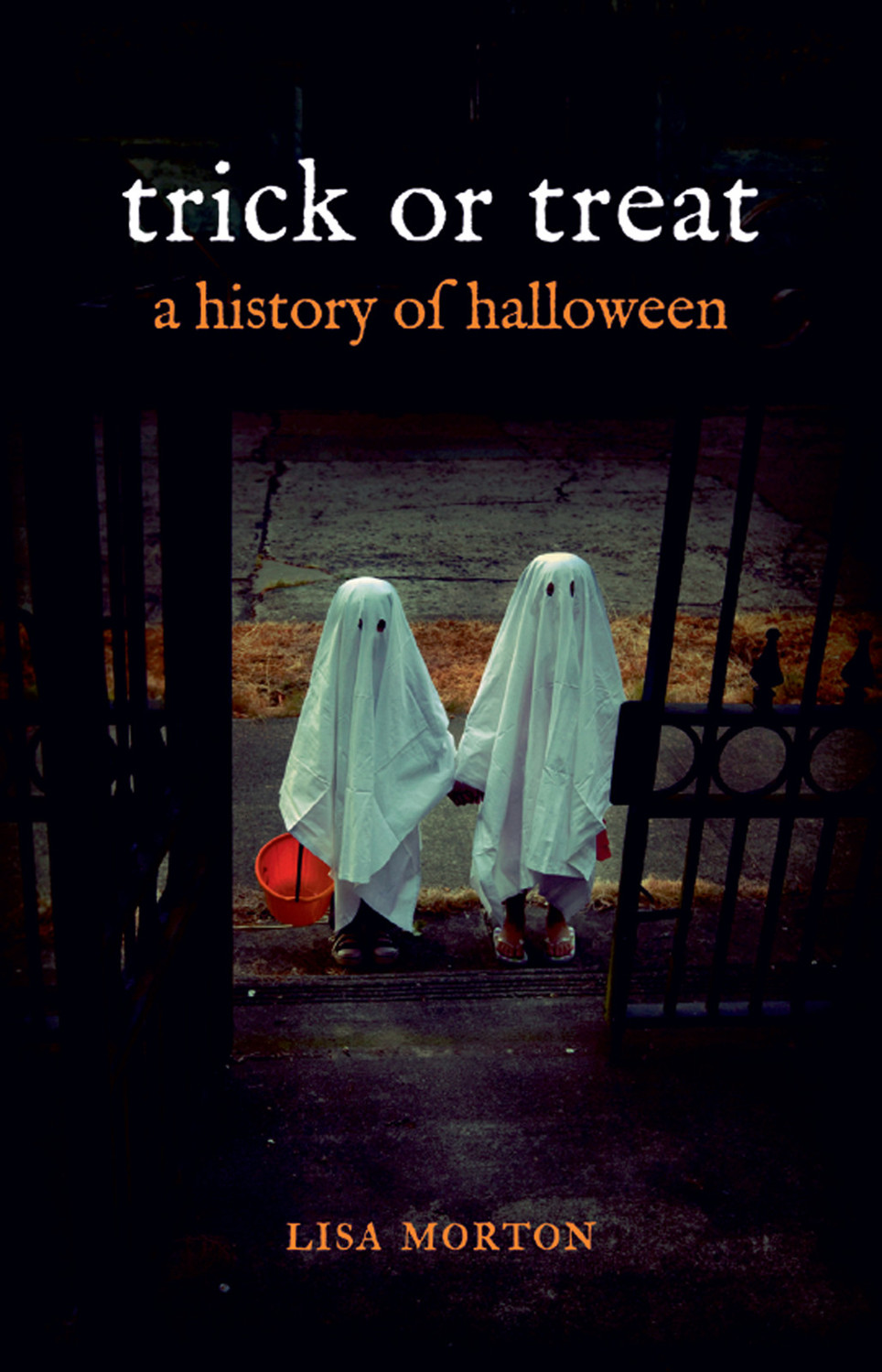

trick or treat

trick or treat

a history of halloween

LISA MORTON

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC V DX , UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2012

Copyright Lisa Morton 2012

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book

Printed and bound in China

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Morton, Lisa, 1958

Trick or treat: a history of Halloween.

1. Halloween History.

I. Title

394.2646-dc23

e ISBN : 9781780230559

Contents

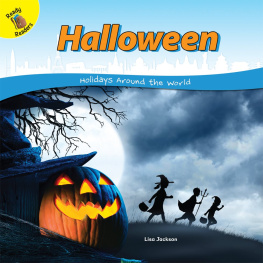

Halloween jack-o-lanterns.

Introduction

Halloween is surely unique among festivals and holidays. While other popular calendar celebrations, including Christmas and Easter, have mixed pagan and Christian traditions, only Halloween has essentially split itself down the middle, offering up a secular or pagan festival on the night of 31 October and sombre religious observance on the day of 1 November. As with Valentines Day, many of those who celebrate Halloween are unaware of its Catholic history or meaning; but while Valentines Day has remained recognizably the same for at least a century, Halloween has transformed over and over again. What began as a pagan New Years celebration and a Christian commemoration of the dead has over time served as a harvest festival, a romantic night of mystery for young adults, an autumnal party for adults, a costumed begging ritual for children, a season for exploring fears in a controlled environment and, most recently, a heavily commercialized product exported by the United States to the rest of the world.

Halloween also has the unenviable distinction of being the most demonized of days: Christian groups decry it as The Devils Birthday, authorities fear its effect on public safety and nationalist leaders around the world denounce its importation for conflicting with their own native traditions. Some of these concerns may be valid, but they are all rooted in a history that compounds confusion and error with occasional fact. Perhaps because Halloween has always been connected with the macabre, those who have chronicled it in the past have frequently been less interested in accuracy than in dramatic and ghoulish ramblings.

Despite a history extending back well over a millennium, its only been within the last three decades that historians, folklorists and writers have begun to take the study of Halloween seriously. Even in that brief period of time, the days identity has shifted, making it difficult to produce a comprehensive and up-to-date overview. Within the last year alone, Halloween has expanded into parts of the world where it was previously unknown, and in its main home, America, industries spawned by Halloween are starting to move beyond mere October celebrations. Halloween is truly becoming more than just a (mostly American) mark on the calendar; its on the verge of blossoming into a global subculture.

Trick or Treat: The History of Halloween is the first book to look at both the history of the festival and its growth around the world in the twenty-first century. As such, it will hopefully serve to fill a gap in the understanding of Halloween, and to capture as detailed an image as possible of where it stands at this time because, given the astonishing speed with which the festival continues to transform and expand, its an image that will undoubtedly change again soon.

Halloween:

The Misunderstood

Festival

In 1762, British military engineer Charles Vallancey was sent to Ireland on a surveying mission. Vallancey, however, was no ordinary engineer: he was extraordinarily well-read in history and linguistics, corresponded with many of the leading proponents of the then-fashionable Orientalism and fancied himself a scholar and writer. He soon developed an obsession with the lore and language of Irelands ancient Celts, and he wrote hundreds of pages of collected fact, observation and speculation on the green isles early inhabitants.

There was just one problem: much of what Vallancey recorded was wrong.

By 1786, when Vallancey published the third volume of his opus Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis , it was already well established that the name Samhain (pronounced sow-in) referred to the three-day Celtic New Year celebration that began when the sun went down on 31 October. Other linguists had recorded the translation of summers end for Samhain, but Vallancey believed this was a false derivation, and went on to state that Samhain was actually a Celtic deity who was also known as BALSAB ... for Bal is lord, and Sab death.

It didnt seem to matter much that the name Balsab appears nowhere else in Celtic lore, or even that Vallanceys work was dismissed during his lifetime (the Orientalist scholar Sir William Jones said of Vallancey, Do you wish to laugh? Skim the book over. Do you wish to sleep? Read it regularly

Romanticized image of a Druid sacrifice, c . 1880.

How is it possible that religious and community leaders would use the writings of a romantic who was denounced in 1818 as having written more nonsense than any man of his time in order to denounce a major celebration? How could the history of what has become, in America at least, the second most popular holiday of the year be so little known?

Halloween is undoubtedly the most misunderstood of festivals. Virtually every English-speaker in the world can instantly tell you where the name Christmas comes from they could probably also provide an anecdote about St Patrick and his Day, and of course those celebrations with simple declarative titles, like New Years or Fathers Day, require no great linguistic skills but amazingly few understand so much as the origin of the name Halloween. The word itself almost has a strange, pagan feel which is ironic, since the name derives from All Hallows Eve. Prior to about AD 1500, the noun hallow (derived from the Old English hlga , meaning holy) commonly referred to a holy personage or, specifically, a saint. All Saints Day was the original name for the Catholic celebration held on 1 November, but long after hallow had lost its meaning as a noun the eve of that day would become known as Halloween.

Halloween owes part of its legacy of confusion and obfuscation to those same Celts who provided the basis for the celebration with their Samhain. Surprisingly little is known of them since they kept no written records. Our knowledge of Irelands Celts is based largely on orally transmitted lore (much of which was recorded by Christian monks of the first millennium) and scattered archaeological evidence. Its no wonder that writers like Vallancey the ones with a more exotic take on history dreamt of a race of savages who offered up human sacrifices to demonic gods and spent the autumn warding off evil spirits by constructing huge, roaring bonfires. By the mid-twentieth century, Halloween historians had added another mistake to their understanding of the day, stating that it was based in part on a Roman festival called Pomona, when in fact there was no such celebration. In the 1960s, a veritable cult of urban legends built up around Halloween especially the notorious razor blade in the apple myth, which suggested that innocent young children were at risk during the beloved ritual of trick or treat although there were no recorded instances of real cases behind these modern myths. Over the next few decades, there were reports of anonymous psychos poisoning candy, costumed killers stalking college dorms on Halloween night and Satanic cults offering up sacrifices of black cats, and warnings of gangs initiating new members by committing murders on 31 October. It sometimes seems as though the prank-playing and mischievousness that have been a key factor in Halloween celebrations for hundreds of years have crossed over and played tricks on its history.

Next page