W HEN M AC WAS THREE YEARS OLD AND A NYA WAS FIVE, they watched their mother get arrested for a seatbelt violation. It was 1997, and the family was driving slowly, about fifteen miles per hour, around the park in their hometown of Lago Vista, Texas, because Mac had lost his special toy. The children had taken off their seat belts so they could look out the car windows for the toy. Officer Bart Turek pulled them over and began yelling and pointing his finger in Gail Atwaters face. Youre going to jail! he hollered. Atwater asked if she could take her wailing children to a friends house first, but Officer Turek said the children would go to the jail right along with her. Gail Atwater was handcuffed, taken to the police station, and locked in a cell. She was booked and fingerprinted for the misdemeanor seatbelt violation. Eventually she paid the maximum penalty for her offense, which was $50. Afterward, both children were terrified of police cars. If Mac saw a police officer, he would get down on the floor and curl up into ball. But the law permitted Officer Turek to do everything he

A few years later across the country in New York, nineteen-year-old Sharif Stinson had a different sort of encounter with the misdemeanor system. Stinson visited his aunt in the Bronx every week to see how she was doing. One day, as he left his aunts apartment building, police ordered him up against the wall. They searched him, and although they found nothing, they arrested him and took him to jail. After four hours, he was released and charged with disorderly conduct. Stinson hadnt actually committed any crime, and a judge dismissed the charge, calling it legally insufficient. Three weeks later, Stinson was back checking on his aunt. Once again, he was stopped, arrested, and jailed. This time he was charged with trespassing as well as disorderly conduct. Once again, he hadnt committed any crimes, and a judge dismissed the charges. These sorts of arrest practices have become controversial in New York. Some New York police officers attribute them to informal quotas requiring that police clock a certain number of arrests and citations or risk professional discipline. The New York Police Department denies the quotas.

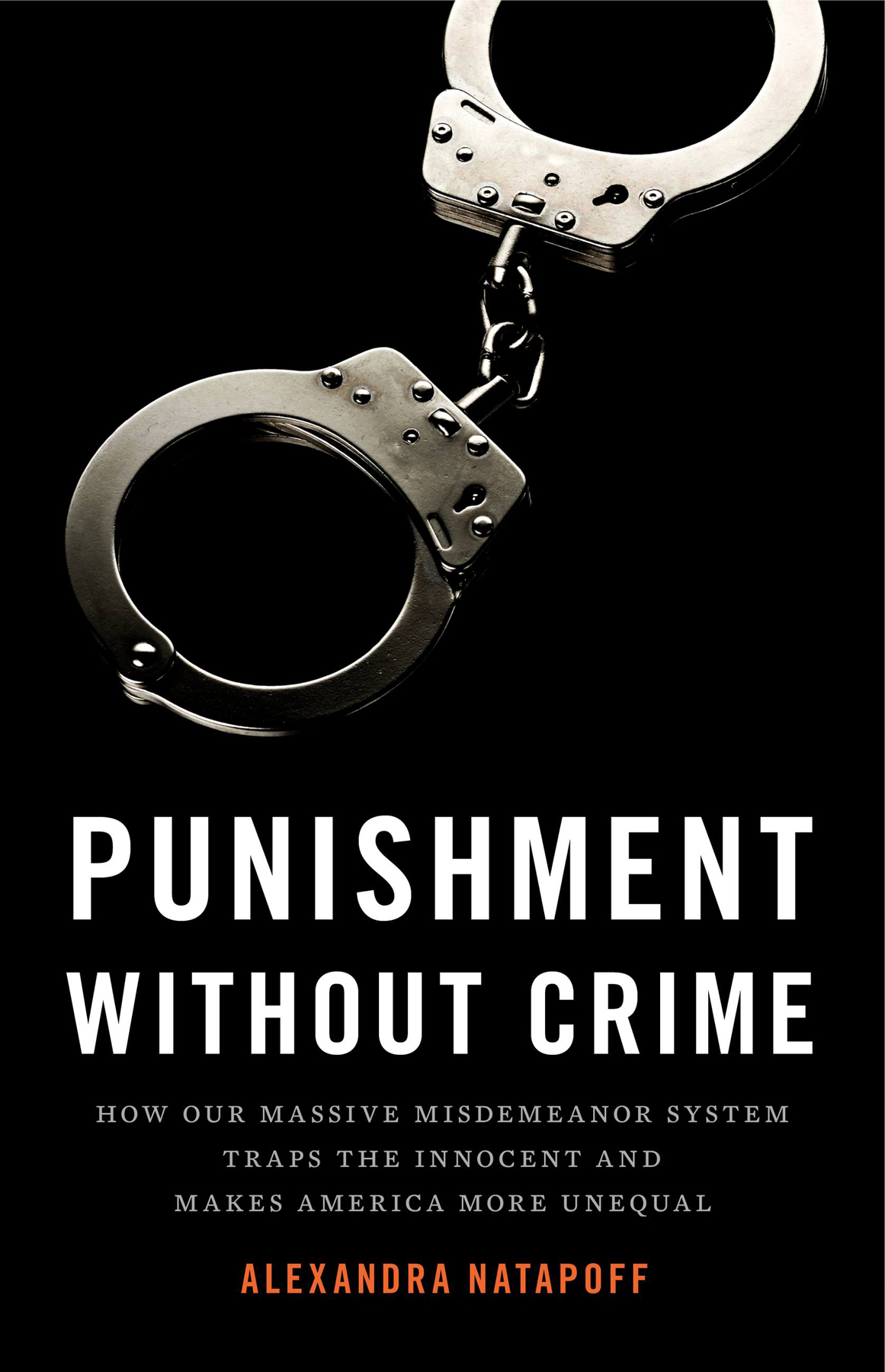

Misdemeanors like Gail Atwaters traffic violation and Sharif Stinsons disorderly conduct charges are the chump change of the criminal system. They are labeled minor, low-level, and petty. Sometimes they go by innocuous names like infraction or violation. Because the crimes are small and the punishments relatively light in comparison to felonies, this world of low-level offenses has not gotten much attention. But it is enormous, powerful, and surprisingly harsh. Every year, approximately 13 million people are charged with crimes as minor as littering or as serious as domestic violence.perhaps jailed, convicted, and punished in ways that can haunt them and their families for the rest of their lives. While mass incarceration has become recognized as a multi-billion-dollar dehumanizing debacle, it turns out that the misdemeanor behemoth does quieter damage on an even grander scale.

Misdemeanors have slipped beneath the public radar largely because their impact and importance are so thoroughly underestimated. Punishments are usually deemed minor, but there is nothing petty about them. The misdemeanor process commonly strips the people who go through it of their liberty, money, health, jobs, housing, credit, immigration status, and government benefits. Even a brief stint in jail can be dangerous. People with misdemeanor arrests and convictions often lose their jobs and find it hard to get new ones. Fines and fees lead to incarceration for those who are too poor to pay them. Students, poor people, and the elderly can lose their government aid. For immigrants, a misdemeanor can trigger deportation. The petty-offense process does all this punishing quietly, often informally, without much fanfare, millions of times a year.

Sometimes misdemeanors dont even look much like crimes. In twenty-five states, speeding is a misdemeanor. Loitering, spitting, disorderly conduct, and jaywalking belong to a large group of crimes called order-maintenance or quality-of-life offenses, and they make it a crime to do unremarkable things that lots of people do all the time. By contrast, some misdemeanors are quite seriousdrunk driving and domestic assault for example. The spectrum is wide: as we will see, some misdemeanors punish the same sorts of harms that felonies do, while many others go after common conduct that isnt particularly blameworthy or harmful at all. Because the law designates such a vast array of common behaviors as criminal, rendering a nearly unlimited number of people potentially subject to its reach, the misdemeanor system is enormous.

Because the petty-offense process is so large, it tends to move cases fast. This has earned it some choice nicknames like cattle herding, assembly-line justice, meet em and plead em lawyering, and

Grandma Gs experience was typical in a couple of ways. First, it was fast. In Florida, most misdemeanor cases are resolved by guilty plea in three minutes. Proceedings in the Hot Check Division of Sherwood District Court in Arkansas last less than two minutes. Some St. Louis municipal courts handle over five hundred cases in a single night court session, less than one minute per case.

Even when defendants do get lawyers, they still might not get proper representation. Many public defenders are burdened with hundreds and sometimes thousands of cases and therefore cannot give time or attention to any one of them. In cities like Chicago, Atlanta, and Miami, misdemeanor public defenders carry over 2,000 cases a yearover five times the caseload recommended by the American Bar Association. Such overburdened attorneys may simply inform their clients about the deal offered by the prosecutor and get them to sign. Hence the nickname meet em and plead em.