Contents

About the Book

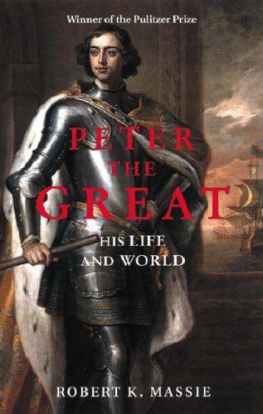

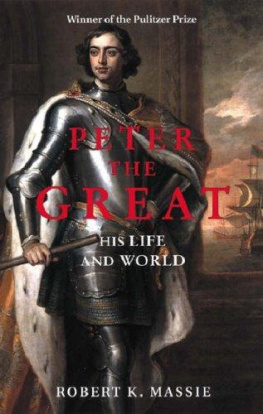

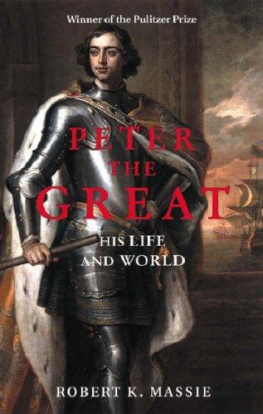

There has never been a more remarkable national leader in modern history than Peter the Great (16721725). He was a giant in every way. In physical stature, willpower, enthusiasm, energy, libertinism and his refusal to accept old conventions, he stood head and shoulders above his contemporaries. He grew up in an atmosphere of fear, suspicion and court rivalries which often assumed violent forms. He only gained power, at the age of seventeen, by ousting his half-sister, Sophia, and shutting her up in a nunnery. As a product of the system, Peter was, of necessity, ruthless and tyrannical, personally carrying out the execution of defeated rebels and even effecting the death of his own son.

But there his identification with Russias past ends. For what has earned Peter his place in history is his success in tearing his country, kicking and screaming, from its traditional, oriental customs and beliefs and integrating it into the life of Europe. He removed the privileges of the medieval aristocracy, brought the Church under state control, and rejected the old Russian calendar in favour of the dating system used in Europe. He even ordered his courtiers and officials to shave their traditional beards and adopt Western dress codes. He avidly studied the latest scientific and technological advances and employed them to build a modern army and to create from scratch a Russian navy. These forces he used to devastating effect by destroying the Swedish empire and making Russia (with its brand new capital, St Petersburg) master of the Baltic.

European leaders did not know what to make of this eccentric, unsophisticated tsar who loathed pomp and ceremony, served as a junior officer in his own armed forces and indulged in rowdy, boorish behaviour. Yet, by the end of his remarkable reign, this man, who had made a servant girl his own wife and empress, had married members of his family into the royal houses of Europe. Thanks to Peter the Great, Russia was profoundly changed. So was Europe.

Derek Wilson tells his extraordinary story with a verve and atmospheric detail that emphasises vividly the impact this one man made not only on Russia, but also on the wider world. Peter the Great created a new Europe in which, for good or ill, Russia was to play a crucial part. His contemporaries were obliged to come to terms with him. And today, it is perhaps even more important for us to understand the historical context and the pivotal role Peter played in the creation of a whole new order.

About the Author

Derek Wilson is well known through his books, radio and TV appearances, frequent journalistic features and festival appearances as one of the UKs leading narrative historians. To find out more about him and his books, visit his website at www.derekwilson.com.

Also by Derek Wilson

ROTHSCHILD: A STORY OF WEALTH AND POWER

SWEET ROBIN: ROBERT DUDLEY EARL OF LEICESTER

HANS HOLBEIN: PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN MAN

THE KING AND THE GENTLEMAN: CHARLES STUART AND OLIVER CROMWELL 15991649

IN THE LIONS COURT: POWER, AMBITION AND SUDDEN DEATH IN THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII

ALL THE KINGS WOMEN: LOVE, SEX AND POLITICS IN THE LIFE OF CHARLES II

CHARLEMAGNE: THE GREAT ADVENTURE

OUT OF THE STORM: THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF MARTIN LUTHER

A BRIEF HISTORY OF HENRY VIII: KING, REFORMER AND TYRANT (Brief Histories)

TUDOR ENGLAND (Shire Living Histories)

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH REFORMATION (Brief Histories)

THE PLANTAGENETS: THE KINGS THAT MADE BRITAIN

PETER THE GREAT

Derek Wilson

Illustrations

. Jacopo Amiconi. Peter I with Minerva, the Allegorical Figure of Glory. Oil on canvas. 231 x 178 cm. Inv. no. GE-2754, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph The State Hermitage Museum

. Peter the Great Presents Truth, Religion and the Arts to Ancient Russia. Unsigned engraving from an original by Frederick Ottens (1725), in John Motley, History of the Life and Reign of the Empress Catherine (London, 1744). Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library

. Alexei Fyodorovich Zubov. Panorama of St. Petersburg, 1716. Etching. 75.6 x 234.5 cm. Inv. no. ERG-17079, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph The State Hermitage Museum

. Tsar Alexei (Alexis Mikhailovich) in ceremonial attire Oleg Lastochkin/RIA Novosti

. Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. The Return of the Prodigal Son, circa 1668. Oil on canvas. 262 x 205 cm. Inv. no. GE-742, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph The State Hermitage Museum

. The Morning of the Execution of the Streltsy in 1698, 1881 (oil on canvas) by Vasily Ivanovic Surikov (18481916) Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia/The Bridgeman Art Library

. Bust of Peter and a boat similar to the one on which he learned to sail (Courtesy of the author)

. The dining room in the simple cabin where Peter lived while St. Petersburg was a-building (Courtesy of the author)

. Peter the Greats small cart at the History Museum Mikhail Filimonov/RIA Novosti

. Peter the Great and Little Louis XV, in A Popular History of France from the Earliest Times by Francois Pierre Guillaume Guizot, Vol. VI.

. Portrait of Catherine I With an African Servant by Ivan Odolsky the Elder, circa 1750 RIA Novosti

. Elizabeth Petrovna, Elizabeth I Tsarina of Russia, (17091762), the youngest daughter of Peter The Great and Catherine I, circa 1730. Original Artwork: Engraving by Mecov after Benner. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

. Alexei Fyodorovich Zubov. The Wedding Feast of Peter I and Catherine in the Winter Palace of Peter I in St. Petersburg February 19, 1712. Etching, chisel, 1712, from the collection of The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg RIA Novosti

. Charles Simono, after Pierre-Denis Martin II, Battle between the Russian and Swedish Armies near Poltava on 27 June 1709. Hand-coloured etching. 61 x 79 cm. Inv. no. ERG-17101, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph The State Hermitage Museum

. Peter I the Great (16721725), 1907 (gouache on card), by Valentin Aleksandrovich Serov (18651911) Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia/The Bridgeman Art Library

. The Naval Engagement at Grengam by Alexei Zubov, 1721 The State Russian Museum/CORBIS

. The Peter and Paul Fortress

. The Summer Gardens in St. Petersburg

. Alexander Menshikov. Reproduction of Alexander Menshikovs (1673 1729) portrait by an unknown painter, from the State Hermitage Museum collection RIA Novosti

. Alexander Menshikovs House by Alexei Zubov, 1717 RIA Novosti

. Peters tomb in the Peter and Paul Cathedral (Courtesy of the author)

. Statue of Peter by Mikhail Shemiakin, 1991 (Courtesy of the author)

. The Bronze Horseman by Etienne Falconet, erected by Catherine the Great (Courtesy of the author)

In his hand Peter found only a blank sheet of paper and he wrote on it: Europe and the West. Since then we belonged to Europe and to the West.

Peter Chaadaev

Introduction

Anyone who can remember the televised images of the destruction of the Berlin Wall in 1989 is unlikely to forget them. The dramatic pictures of people tearing at masonry with machines, picks and bare hands, of family members tearfully reunited, of faces radiant with excitement and hope stand vividly in our memories. We felt rightly that we were watching history. The Soviet empire was not only crumbling; its people were coming back into the European fold. Integration promised an end to the Cold War. More it held out the hope that a shared culture embracing East and West could permanently remove the fear of armed hostility. Behind it lay two decades of political and diplomatic activity arms limitation treaties, rebellions in Soviet satellite states and the progress of European union. It was this last phenomenon that played decisively with Mikhail Gorbachev, the atypical Soviet General Secretary and, subsequently, President, who held office from 1985 to 1991, and who initiated the massive policy changes on the far side of the Iron Curtain. He was impressed by the growing economic strength of the emerging European Union and its apparent success in curbing the nationalism that had been the curse of the twentieth century. Closer contact with western Europe would, he believed, put an end to the crippling arms race, thus freeing revenue for vital modernisation, and provide better access to commercial markets. It would enable Russia to incorporate elements of the Western value system without kowtowing to the USA. His attitude did not fall far short of a vision for civilising Russia by strengthening ties with the family of nations to the west from which it had been estranged since 1917. Most visitors who have seen Russia under the old regime and the new cannot but believe that Gorbachev was right. They are struck by the rapidity and comprehensiveness of the transformation that has come over society since the early 1990s. Creeping capitalism has established itself, for good and ill. City streets are clogged with motor cars. Shop windows glisten with desirable luxuries. Tourism flourishes both inward and outward. Bars are thronged with middle-class citizens with disposable income. There is a new pride in the countrys pre-Soviet heritage. To see all this is to gain some idea of what happened in Russia three hundred years ago.

Next page