Alexei Navalny - Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia

Here you can read online Alexei Navalny - Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Egret Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

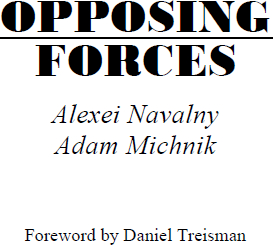

- Book:Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia

- Author:

- Publisher:Egret Press

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2015 Alexei Navalny, Adam Michnik

The right of Alexei Navalny, Adam Michnik, and Daniel Treisman to be identified as the Authors of the Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in Russian by Novoe Izdatelstvo (New Press), Moscow 2015

First published in translation in Great Britain in 2016 by EGRET PRESS

Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-0-9933869-5-4

Translated by Leo Shtutin

Editors: Jeremy Noble, Vladimir Ashurkov, Laura Gozzi

Cover design by Stuart Bache

All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted by UK copyright law, no parts of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written consent from the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency

EGRET PRESS

London

Contents

The written record of an animated discussion in Red Square, between a Russian and a Pole, talking about any number of controversial matters, within sight (and probably hearing) of the Kremlin, was always going to cause consternation and not a little excitement. But the editors task is to elucidate and adjudicate, not to exclaim and judge that can be left to the reader.

Grateful thanks should go first to Daniel Treisman for agreeing to write the foreword, which elegantly places the discussion between Alexei Navalny and Adam Michnik both in its historical and contemporary context.

In the course of these perambulations around Red Square, many people, historical and living, are mentioned, some in passing, some in depth. It was felt that one could not decide how many of these people would be known to the reader; and at the risk of somebody exclaiming I know who Gorbachev is! there is an extensive glossary of (hopefully all) the people discussed, and sometimes dissed. Likewise, there are a, by no means exhaustive, number of endnotes, the purpose of which is to give to the reader just as much background as might be necessary to shed light on an event, no matter if it took place recently or in the dim and distant past.

Which brings one to the biggest editorial conumdrum of all spelling. Does one write Lvov? Lviv? Lww? Since were talking about the Polish perspective ; and what about Vilnius vs Wilno? Oh, the arguments there have been about a particular spelling; this one signifying support of Russian imperialism, that one trampling on the sensitivities of the Poles, another one ignoring the yearnings of the Ukrainians The result was that the only consensus to be found lay in choosing whatever spelling the reader would likely find most familiar (then why not, one asks, Alexander instead of Aleksandr ).

If only an editor could be as brave as Alexei Navalny and Adam Michnik, when it comes to words, but an editor has no place behind the barricades, rather, one takes shelter behind the full stop.

There are moments in unfree societies when the perceptions of millions suddenly converge. A controversial article slips through the censors net and sparks conversations nationwide. A tiny protest metamorphoses into a multi-city uprising. Always unexpected, such events tend to develop rapidly, like a crisis on the stock exchange.

Whatever the details, such moments are, first and foremost, moments of mutual recognition. Citizens realise they are not alone; they constitute a group, a class, a nation. A community sometimes for the first time sees itself. And that experience of seeing and being seen is, in fact, what makes it a community.

The result is not necessarily a revolution or other political change. But such moments transform the social landscape, creating new actors and new consciousness. They show how the tectonic plates have shifted. Those in power often respond with violence. However, while clubs and threats can force people back into their apartments, it is much more difficult to erase their memory of the experience. One cannot shoot a moment. Once seen, a community is hard to unsee.

Something like this occurred in Moscow in December 2011. That winter, residents of the capital began to congregate in the citys central spaces. They came in tens sometimes hundreds of thousands. Previously apolitical lawyers, artists, lecturers, writers, businessmen, and many other members of a small but growing middle class found themselves thronging to such gathering points as Marsh Square actually an avenue on a crescent-shaped river island or the appropriately named Sakharov Prospect.

The trigger was the blatant fraud that hundreds of volunteer observers had recorded during the recent parliamentary election. Protesters demanded a new ballot. But concerns soon broadened. Some began to call for President Putins ousting. In the Kremlin, officials watched with confusion and then alarm.

Those who met in the squares came away changed. They saw others like themselves, thousands of them. The journalist Maxim Trudolyubov, strolling among the crowds, experienced a strange kind of dj vu. He kept seeing faces that looked familiar although, he realised, most of them were not.

Many speakers addressed the meetings that winter popular writers, leftists, nationalists, environmentalists even Putins former finance minister, Alexei Kudrin. But the one who best caught the mood of the listeners was a 35-year-old activist named Alexei Navalny.

Forty-three years earlier, a similar moment of awakening had transfixed Warsaw. In January 1968, students mobbed the final performance of a production of Dzyady [Forefathers Eve], an epic drama by the 19th Century romantic bard Adam Mickiewicz. The Communist authorities had forced the theatre to cut short its run after audiences started cheering the plays anti-Russian allusions.

A 22-year-old history student named Adam Michnik reported the events to a journalist from Le Monde, whose account was then broadcast by Radio Free Europe. Michnik was expelled from the university and arrested. That March, Warsaw University students held a large demonstration in Michniks defence, and to demand an end to censorship and Soviet domination. They were brutally suppressed by the riot police and worker squads. Unexpectedly, student strikes broke out across the country, in Krakow, Poznan, and other university cities.

Last April, these two men met in Moscow for a series of informal discussions that stretched across three days. This book is the result. The genre is that of the recorded conversation, a literary form as characteristic of Eastern Europe as the absurdist novel or the anthology of Letters from Prison. Listening in, one almost smells the espresso and cigarette smoke. Michnik is a master of the form. His past partners range from his friend Vaclav Havel to Polands General Wojciech Jaruzelski, from fellow soixante-huitards Daniel Cohn-Bendit and Bernard Kouchner to the poet Czeslaw Milosz.

The meeting occurred at a gloomy time for the democratic opposition in Russia. The protests of December 2011 had petered out over the following year. A barrage of propaganda from the official media had incited fear and anger towards the West and rallied the public behind President Putin. To the delight of almost the entire population, Russia had torn Crimea from Ukraine and annexed it. And then, not long before Michnik and Navalnys conversations, their mutual friend, the Yeltsin-era politician and opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, had been brutally murdered, gunned down on a bridge beside the Kremlin.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia»

Look at similar books to Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Opposing Forces: Plotting the new Russia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.