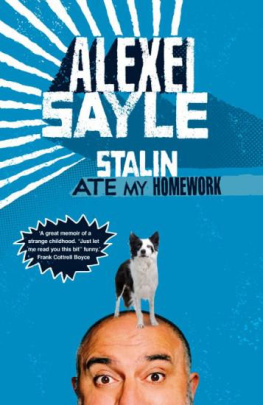

Alexei Sayle - Stalin Ate My Homework

Here you can read online Alexei Sayle - Stalin Ate My Homework full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Stalin Ate My Homework

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stalin Ate My Homework: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Stalin Ate My Homework" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Stalin Ate My Homework — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Stalin Ate My Homework" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Molly.

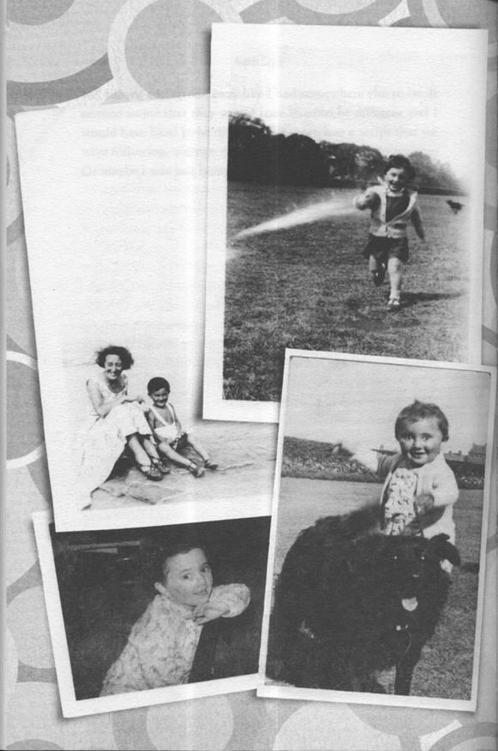

The rumour went round the kids in the neighbourhood like a forest fire: Bambi would be coming to the Gaumont cinema in Oakfield Road. It was a brilliant piece of marketing. Every ten years or so the Disney organisation would relaunch their major cartoon movies so that a whole new generation of children became hysterical with anticipation. Whenever a group of us six-year-olds came together, in the playground at break-time or running around the streets after school, we imagined what the film would be like, conjecturing deliriously and inaccurately on the possible storyline. More than anything else there was some collective sense, some morphic resonance that told us all that seeing Bambi was going to be a defining moment in our young lives.

Usually I was at the centre of any wild speculation that was going on, dreaming up mad theories about the half-understood world the year before, I had successfully convinced all the other kids that peas were a form of small insect. But on this occasion there was something lacking in the quality of my guesswork, a hesitation, an uncertainty which the others sensed, because for me, getting in to see Bambi was going to be a huge challenge. The lives of other children, when they were away from their families seemed to be entirely free from adult interference there was a range of activities such as purchasing comics, seeing films, games of hide-and-seek and tag, buying and playing with toys, that were regarded by both sides as kids things. For my friends, going to see Bambi would simply mean their mum or dad buying them a ticket and then crossing over Oakfield Road to the cinema in a big, noisy gang. My life wasnt like that. It was subject to all kinds of restrictions, caveats and provisos, both physical and ideological. I was never entirely sure what was going to be forbidden and what was going to be encouraged in our house, but I suspected that something as incredible as Bambi was certain to be on the prohibited list and I knew that if I was going to see this film it would be a complex affair requiring a great deal of subtle negotiation, possibly with a side order of screaming and crying.

It wasnt just seeing the film, fantastic as that was likely to be, that obsessed me it was that the whole event represented a dream not exactly of freedom but of equality. I had begun to suspect that we werent like other families. There were things we believed, things we did, that nobody else in the street did, things that inevitably marked me out as different. What I really longed for and what I thought going to the pictures to see Bambi would give me was a chance, for once, to be just one of the crowd. I was convinced that, by taking part in such a powerful cultural event as the first showing for a decade of this animation masterpiece, everything that was confusing about other peoples behaviour would become clear and all that was strange about my own would somehow magically vanish. I would be exactly like everyone else.

My parents needed to understand that they had to allow me to see Bambi! But they didnt. Whatever pleas I made, whatever tantrums I threw, they steadfastly refused to let me go. They had two reasons. My parents disapproved of most of the products of Hollywood but they had a particular dislike for anything made by the Walt Disney company Uncle Walt had been an enthusiastic supporter of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his anti-Communist witch-hunts of the early 1950s, so they hated him for that. But even if he hadnt been a semi-fascist they would still have had an aversion to his gaudy cartoons and sentimental wildlife films. More significantly in this case, my mother had the idea that I was a sensitive, delicate, artistic boy and she was worried that I would be distressed by the famously child-traumatising scene in which Bambis mother is killed by hunters in the forest.

Yet they didnt wish to be cruel. They understood that I was missing out on seeing an important and culturally significant film, so as a consolation the three of us took the 26 bus into town to attend a screening of Sergei Eisensteins 1938 film Alexander Nevsky at Liverpools Unity Theatre. In Alexander Nevsky there are several scenes of ritualistic child sacrifice and a famous thirty-minute-long sequence set on a frozen lake beside the city of Novgorod in which Teutonic knights in rippling white robes, mounted on huge snorting metal-clad stallions, only their cruel eyes visible through the cross-shaped slits in their sinister helmets, charge the defending Russian soldiers across the icebound water. When they are halfway over, the weight of their armour causes the ice to crack and the knights tumble one by one into the freezing blackness. Desperately the men and their terrified, eye-rolling horses are dragged beneath the deadly water, leaving not a trace behind them.

As I sat in that smoky, beer-smelling room, stunned and disturbed by the flickering black and white images on the screen, it began to dawn on me that all my efforts to be one of the crowd, to be just like the other kids in the street, were doomed to failure. That no matter how hard I tried, I was always going to be the boy who saw Sergei Eisensteins Alexander Nevsky instead of Walt Disneys Bambi.

My maternal grandfather, Alexander Mendelson, the shamas a combination of caretaker and secretary of the Crown Street Synagogue, died not knowing that his daughter was married to a non-Jew, was expecting a child, had joined the Communist Party and was living in a terraced house in Anfield at the opposite end of Liverpool. My mother experienced a great deal of conflict over not telling her father about her new life and her baby, but if a girl married out of the Jewish faith the common practice amongst devout families was to sit shiva for them, to mount the week-long period of grief and mourning held for a dead relative and then to treat the errant daughter as if she was in fact dead. She may have wished to be open with her family, to tell them all about her new circle of friends, this new faith she had found and her new husband, but she convinced herself that it was safer to lie. My mother informed her parents that she was leaving the family home, also in Crown Street, and moving across to the other side of the city to, as she told them, live in a flat. Once the patriarch was dead she felt able to tell her mother, brother and sisters her true situation. It is a testament to their good nature, and perhaps a little to their fear of my mothers furious temper, that they didnt then cut her off.

My parents met in 1947 at a discussion group called the Liverpool Socialist Club which assembled for talks, debates and lectures of a left-wing nature at the Stork Hotel in Queens Square. Notions of social justice, equality and the communal ownership of the means of production were so fashionable that the owner of this smart city centre venue let them have the room for free, even though they were planning, at some point in the future, to take his hotel off him.

At the time of their marriage my father, Joe Sayle, was forty-three years old and my mother, Malka (also known as Molly) Mendelson, was thirty-two. Molly was the oldest child in a family of nine who lived in the heart of Liverpools poor Jewish quarter. Her mother had been born in the city, but her father was an immigrant who had fled Latvia, then under Russian jurisdiction, as a teenager fearing conscription into the tsarist army During the nineteenth century the Russian authorities would sweep up any Jewish male, some as young as twelve, and not release them from military service for twenty-five years, when they would be dumped, worn out and confused and often thousands of miles away from their home.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Stalin Ate My Homework»

Look at similar books to Stalin Ate My Homework. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Stalin Ate My Homework and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.