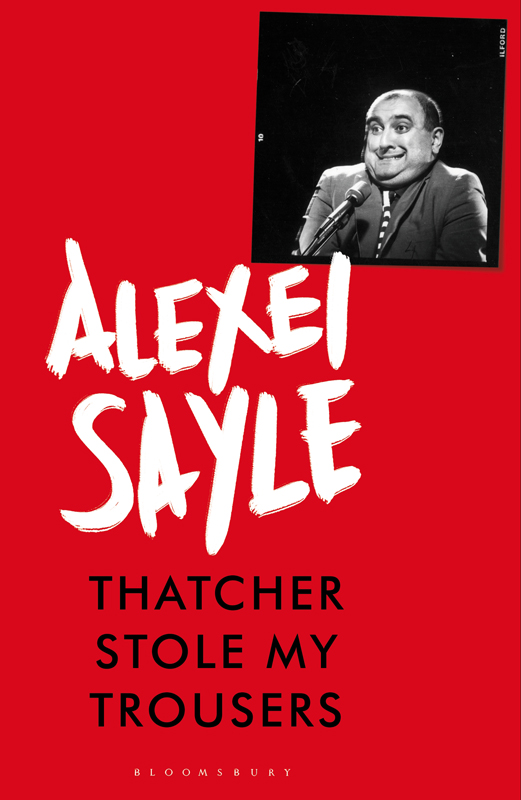

THATCHER STOLE MY TROUSERS

Thatcher Stole My Trousers

Alexei Sayle

For Linda

The twentieth-century philosopher George Santayana once wrote, History is a pack of lies... told by people who werent there. I at least was there.

CONTENTS

All his working life my father was a railwayman. Through his older brothers Joe Sayle got a job on the old Cheshire Lines Committee at the age of sixteen in the year before the General Strike and remained in the railway industry until he retired due to ill health in the late 1960s. The railways became so woven into our daily life that alongside Communism, trains became our family credo. There werent many problems we thought couldnt be solved either by the violent overthrow of capitalism or by getting on a train.

In September 1971 I climbed aboard the sleek jet-plane-like carriage of a blue-and-grey InterCity train that waited imperceptibly humming at the platform of Liverpools Lime Street Station embarking on the most important journey of my life. I settled myself into a plastic, foam and metal seat facing a wide table, gauzy orange curtains hanging at the window. In the buffet car all the food came from a department of British Rail called Travellers Fayre, the spelling of Fayre implying that your food would be cooked by the Knights Templar and served to you by capering jesters, which indeed it often was. In a piece of almost Soviet centralisation, from the Highlands to Cornwall every single item of refreshment in the buffet car was distributed via a central depot in the Midlands so that all produce on the railways was stale days before it reached the customer.

After a few minutes the journey towards the capital began with a surge of electricity and as we emerged from the sandstone tunnels that led out of Lime Street Station I was able to get a good view of a piece of graffiti which had recently appeared scrawled in paint on the wall by the side of the track, a missive which greeted each and every traveller coming from the South. It read in big black letters, FUCK OFF ALL COCKNEYS. This message remained untouched for the next twenty years, despite its being passed by endless maintenance crews whose only action from time to time seemed to be to give it a fresh lick of paint.

This rail journey to London was almost as routine for me as the bus ride to school or the ferry crossing over the River Mersey. Being the son of a railwayman meant I was entitled to free or reduced-price train travel right across Europe, so when I was a child Id frequently taken the four-hour journey with my parents to the capital, to march alongside them on political demonstrations or to accompany Joe to Trades Union Congresses at Southern seaside resorts, or as the first leg of the Continental rail trips we took every summer, firstly to France, Belgium and Holland and then later further east to the Communist countries of Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Later as a teenager Id ridden the train on my own, visiting older friends in the capital, attending art exhibitions at the Tate or the ICA or at the beginning of several doomed European hitch-hiking holidays which inevitably ended with me getting on a train in some European capital and fleeing back home.

This particular journey though felt different. Because I was leaving Liverpool for good and moving permanently to London, any return trips would be as a visitor. The next day would be my first as a student of painting at Chelsea School of Art. Being accepted to study at such a prestigious institution seemed proof to me that I was, as Id always suspected, a truly talented and exceptional individual. Once the letter arrived containing my acceptance I would say to people back home in Liverpool, Yeah, Im going to live in London, man, and Ill be like studying at like only the best painting college in the country. There were like fifteen thousand applicants for twenty places but I got the slot, man.

It had been my strong desire to get away from home, to live in London, for as long as I could remember. There was a boutique called Neils Place on Mount Pleasant in Liverpool where it was said the clothes sold there came from London. That they were as hideous as anybody elses clothes was irrelevant, they came from London and that meant Neil was rich enough to own a rather lovely British sports car styled by Bertone called a Gordon-Keeble, which was always parked ostentatiously outside his shop.

I wanted to move to the capital despite the fact that Liverpool was a city where for its size there was an extraordinary amount going on music, art shows, poetry, football but it still couldnt match London. I would read in the papers about all the rock gigs, exhibitions and plays in the capital and was awestruck. I didnt actually want to go to any of them, I just wanted to live in a place where they were on, where others took on the burden of seeing them all. London was the spot where everything was, and more importantly it was the place where my mother wasnt.

Because they were Communists and mixed in the same radical circles as I did, my parents had recently started turning up in the same pubs and attending the same late-night parties as me. It was not a good idea to have your mother relating anecdotes about your potty training to girls you wanted to get off with.

I wanted to move even though recently Id achieved a great ideological victory over my mother Molly. Molly had suddenly noticed on Mothers Day other children and teenagers in the street coming to visit their mothers, bringing them chocolates and flowers and cooking them breakfast in bed. Angered by the fact that I had done nothing, she started yelling, You never do anything for me! Why dont you do something like the other children in the street for your mother on Mothers Day, bring me flowers or clock radios!

But, Molly, I replied calmly, you expressly told me when I was a child that Mothers Day was a capitalist conspiracy thought up by the floral industrial complex and the fascist greetings-card monoploy to steal the hard-earned cash of the working classes.

Fuck off, Lexi, she said.

Yet though it was my strongest wish to leave home and go to college I was also scared. On the bookshelves in our front room in Valley Road, Liverpool, amongst the serious and mostly wrong volumes from the Left Book Club, there were several optimistic novels of social progress such as Winifred Holtbys South Riding. In South Riding the uplifting conclusion is that the bright working-class girl manages to throw off her proletarian past and, fighting against great odds, gain a place at university. What the novel doesnt mention is the bright girls sense of dislocation, her feeling that she will never again be part of any tribe, neither the one she has left nor the one she is going towards, that she has made a terrible mistake, will be lonely for the rest of her life and people in London will laugh at the provincial cut of her trousers. The bright girls fears in South Riding would have been compounded if shed chosen to begin her new life sharing a damp cellar with a load of Arabs.

Rather than staying in the colleges reasonably priced hall of residence in Battersea Id chosen to take up the offer of a place in the flat of a friend who was already living in London. This turned out to be a foolish choice. As far back as I could remember, and becoming more pronounced once I got to my teenage years, my inclination was to make important life decisions based not upon what was sensible or right or appropriate but rather on what I thought might sound impressive to some imaginary people who lived inside my head. These people encouraged me to make a lot of mistakes.