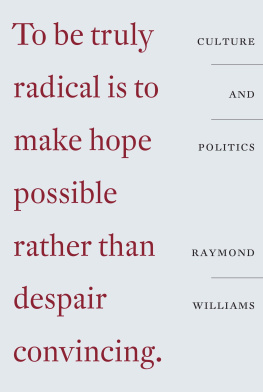

This paperback edition, with a new introduction, first published by Verso 2015

First published by New Left Books 1979

Raymond Williams 1979, 1981, 2015

Introduction Geoff Dyer 2015

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-015-9 (PB)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-017-3 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-016-6 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

Introduction

I come from Pandy The first words spoken by Raymond Williams in this book may not have quite the rolling loquacity of the opening lines of Saul Bellows The Adventures of Augie March I am an American, Chicago born but in their brisk way they bespeak a similar confidence. Bellows narrator immediately situates his experience in the heart of America; Williams announced one of his main concerns in the title of his first novel, Border Country. Borders how they are constructed and recognized, how they impede and are crossed are central to his thought. In contrast to Marchs unequivocal belief I am an American Williams, whose work concentrated on the English literary and cultural tradition, came to identify himself as a Welsh European, emphasizing what lay either side of a presumed centre, both locally and within a larger international context.

It happened that in a predominantly urban and industrial Britain I was born in a remote village, in a very old settled countryside, on the border between England and Wales. This is the account Williams gives of his origins in The Country and the City,).

Confidence counts for little unless it is allied with determination. Combined with an Orwellian sense of the enormous injustice You could almost say he is waiting for the author to coin his most famous term, structure of feeling. Going further back, to Wordsworth in Residence at Cambridge, Williamss thought, even at its most theoretical, is linked with some feeling. Where Williams came from was inextricably linked with what he came to say.

If Orwells sense of the injustice of the world was fed by a disposition to dwell on its misery, then the privileged background of the signalmans son over that of the old Etonian made the idea of defeat almost

This double combination complexity of thought and clarity of expression, with a depth and intensity of personal feeling made Williams a commanding and inspirational figure for the generation of students who came of age in 1968 and looked to him for political and moral as well as intellectual guidance. In some cases former students shared platforms with him, or went on like Eagleton to become colleagues or friends. A representative of the next generation (ten in 1968), I set eyes on him precisely twice.

The first time was when he came to give a lecture at Oxford, where I was an undergraduate, in about 1978 or 79. Our tutor encouraged us to go, so we went. I had no idea who Williams was or what he was droning on about. Then, in the mid-1980s, I went to see him in conversation with Michael Ignatieff at the ICA. Im guessing that the occasion was the publication of his novel Loyalties though if it was, then how come I didnt get my copy signed? And even if it wasnt, why didnt I ask him to sign my copy of Politics and Letters (bought in Collets on the Tottenham Court Road, on 30 March 1983)? I can only assume I was too intimidated because by then the old bloke whod waffled on at Oxford had entirely reshaped my sense of life and literature and the way they were related. The idea of lived experience may have been part of the Leavisite vocabulary but whereas I had read the words in Leavis I experienced them in Williams. Before that, in a way that now seems hard to credit, I had no understanding of the social process Id lived through even though it was, by then, a well-documented one: the working-class boy who keeps passing exams exams that take him first to grammar school, then to an Oxbridge college and discovers only in retrospect that there was more to all this than exams, or even education. Its entirely appropriate that Culture and Society a new way of considering authors with whom I was already familiar played a crucial part in this discovery. All the expected symptoms of the transformative reading experience were in evidence: the feeling of being addressed personally, of ones life making a sense that should have been apparent all along while being conscious, also, that the revelation was happening at just the right time. This was all the more acute because and my gratitude on this score is boundless it occurred independently, after university, not as part of some kind of assigned coursework. At the risk of placing more emphasis on the letters than the politics, I discovered and loved Williams in the way that, and at the same time as, friends were discovering and loving novelists such as Bellow.

And it happened in tandem with my discovery of another writer, John Berger. The Country and the City was published in 1973 and made into a film six years later by Mike Dibb. In 1971 in Ways of Seeing (also directed by Dibb) Berger had encapsulated one of Williamss arguments with a proto-Banksy bit of vandalism: nailing to the tree behind the landowners heads in Gainsboroughs portrait of Mr and Mrs Andrews a sign that reads Private Property Keep Out.

I emphasize the kinship what the author of Culture and Society might have called commonalities between these two not because of their shared place in my autobiography but to pull Williams away from the slightly tweedy company he is assumed to keep. An undergraduate at Cambridge in the early 1990s, Zadie Smith recalls Williams being spoken of as the equal of Foucault or Barthes.absence in these pages is perhaps a sign of how Williamss horizons were and his posthumous reputation is more bounded and hedged by the departmental and institutional borders he claimed to resent). A perverse and ironic fate: Williams, the internationalist, is seen as the worthy relic of a vanished, pre-Thatcherite Britain, a socialist writer read by a diminishing audience of Marxists, academics and students to whom his work is prescribed as retroactive treatment for a sickness (late capitalism) that has infected the furthest reaches of the global body politic. It was the least surprising thing in the world to see, in the Occupy Camp at St Pauls a few years ago, a much-pierced protester reading Bergers Hold Everything Dear; it was equally unsurprising that no one was holding The Country and the City.

I mention that book partly because of its relevance to the issues raised by Occupy, partly because of the moment in this one when the New Left Review interlocutors quote a passage about the great country houses and the landscape that surrounds them (see

The passage itself is unremarkable; what was extraordinary was how thoroughly my reading of it was permeated by the earlier exposure to The Country and the City