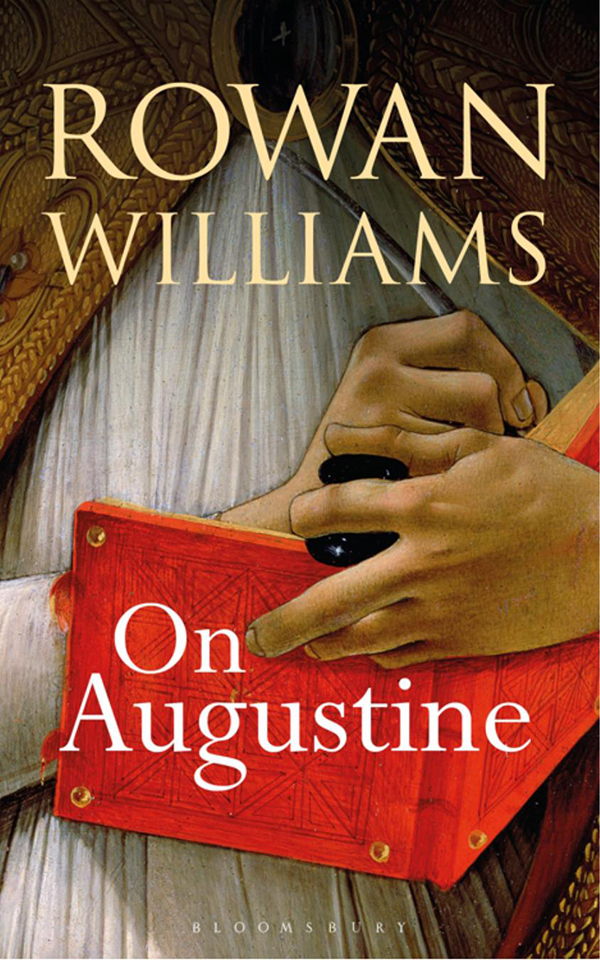

On Augustine

The chapters that follow were written over a long period, more than twenty-five years in fact. Many of them started life simply as part of my own attempts to make sense of Augustines arguments as I taught various texts of his to undergraduate classes. I cant say that I began with any overarching theory about how to read Augustine. But as these essays will show certain themes emerged as holding together aspects of Augustines thinking, and so the reader will find some overlap, even repetition, in the discussions here. What has been intriguing is to see how Augustinian scholarship overall has moved in the last quarter of a century towards a fuller appreciation of Augustine as someone who reflects carefully on a central tension in the human condition between the fact that we have to begin all our thinking and praying in full awareness of our limited, embodied condition and the fact that we are summoned by our creator to go beyond limited and specific desire, reaching out to an endless abundance of life. These essays reflect a small part of that shift in emphasis within the scholarly world a shift that has not gone without some criticism but which has undoubtedly refreshed everyones reading of the saint. It has made it harder to repeat the clichs about Augustines alleged responsibility for Western Christianitys supposed obsession with the evils of bodily existence or sexuality, or its detachment from the world of public ethics, its authoritarian ecclesiastical systems, or its excessively philosophical understanding of Gods unity, or whatever else is seen as the root of all theological evils. Textbooks still recycle some of this, alas, as do popular works of religious history. But the case for the defence is now grounded in a formidable range of learned monographs in most of the main European languages; and it is not likely that we shall ever go back uncritically to the earlier paradigms.

In pursuing these readings of Augustine over the years, I have been helped and stimulated more than I can readily say by many colleagues and students. Apart from the immense encouragement of older scholars who had done so much of the groundwork for a new approach to Augustine especially Gerald Bonner, Henry Chadwick and Robert Markus I owe a great debt to a number of younger researchers, some of whom I had the privilege of supervising for part of their studies. Among this younger generation, Lewis Ayres, Michel Barnes, Robert Dodaro and Carol Harrison have been particularly important in educating me further. More recently, I have benefited from the work of writers like Luigi Gioia, Michael Hanby, Roland Kany, Charles Mathewes, Edward Morgan, Lydia Schumacher, Susannah Ticciati and, of course Miles Hollingworth, whose brilliant synthesis of 2013, Saint Augustine of Hippo, draws so many threads of research and interpretation together. In addition to this, I must express my gratitude to other participants in various conferences on the saint in Dublin, Lancaster, Toronto and Marquette University and in seminar groups and master classes at successive Oxford Patristics Conferences, where several of the ideas in these chapters had their first airing. The new look in Augustinian studies has made some impact in the wider world of philosophical theology, and the studies collected here have been enriched by conversation with John Milbank, Catherine Pickstock and Graham Ward. My thanks are also due to many friends in the Order of Saint Augustine, in Ireland, the UK and the United States, for generous hospitality and warm support. For several years I had the delight of sharing with the Revd Anthony Meredith SJ the teaching of an Augustine special subject paper in the Oxford Honours School of Theology; his patient, acute and precise interpretations of the texts were a constant stimulus (and reproach) to a less exact mind. And finally, Robin Baird-Smiths enthusiasm for assembling these essays into a book has been a stimulus to get back to work on them; several exasperated researchers over the years have lamented that many of these pieces were proving inaccessible because they had been published in rather out-of-the-way places, and they have Robin to thank for persuading me to pull them together. As always, my gratitude for his support is very great.

Not all of these essays are designed as full-blown academic studies and none of them is primarily concerned with strictly historical or chronological issues. than on their use in contemporary debates on various subjects. I am also aware that these essays include no extended discussion of the major controversies of Augustines episcopal career, the struggles with Donatism and Pelagianism, though these are touched on in passing. This is largely the result of which texts I happened to be teaching, but also of an interest in the fundamental categories of Augustines work (the nature of human identity or finite selfhood in its relation to God, the character of Trinitarian divine love and its embodiment in Christ) from which I believe the specific doctrinal concerns about grace and the limits of the Church derive. I hope that the themes outlined in these essays will help to make better sense of certain aspects of Augustines engagement in these particular controversies; but I recognize that the absence of any treatment of these significant dimensions of Augustines concerns means that this book has no claim to be a comprehensive approach to the saints works.

As I have indicated, research on Augustine has flourished abundantly in the last few decades. Rather than rewriting all these pieces so as to take account of more recent work, I have decided to add some brief extra material after some chapters or groups of chapters so as to give some indication of the sort of direction taken by scholarship and interpretation in the years since the original delivery or publication of the essays. These new sections do not aim to provide an exhaustive bibliography, but they should at least sketch in some of the ways in which the field continues to develop.

It will be obvious that I believe Augustine to be a thinker supremely worth engaging with not only as a specifically Christian mind but as someone whose understanding of subjectivity itself, of what it is to be a speaking and thinking person, is of abiding interest. He grasps, as few if any pre-modern writers did, the way in which the shaping of a sense of self is a narrative business: our memory is central to whatever we mean by the life of spirit, conscious appropriation of who we are, and so even if we are seeking a perspective on ourselves and the world that is not bound to the changing life of a material environment, we cannot avoid coming to terms with how the passage of time is inscribed in our knowing (of ourselves and of our world). We cannot develop a practice that will simply allow us to leave time and the body behind and it is something of this absorption in time and the body which makes sense of Augustines suspicion of both the search for the perfect Church and the idealizing of a contextless free will that is, his suspicion of what might underlie Donatism and Pelagianism. In an intellectual culture deeply confused about the self, its reality and continuity, Augustine offers some searching and constructive questions about what we know, dont know, cant know and cant doubt in our awareness of ourselves as thinking beings. And for him this is inextricably bound in with how he reads his own story as one in which the embodied Word of God speaks to and engages with him in the actualities of history, drawing him into a relation with the divine that is in itself eternal and limitless and always rooted in what is learned within a community of material others here and now. He deserves all the lavish attention he has received over the centuries; my hope is that these reflections may prompt some beyond the community of Christian belief and belonging to read him afresh as a thinker who illustrates beyond any doubt that Christian theology can be a vehicle for the most serious reflection on the nature of our humanity: its varieties of self-enslavement, its obscurity to itself, its emergence in relatedness and reciprocity.

Next page