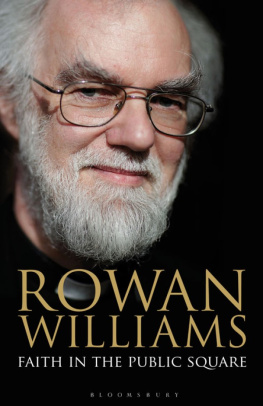

Faith in the Public Square

Rowan Williams

Bloomsbury Continuum

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

www.bloomsbury.com

Blooomsbury, Continuum and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2012

Paperback edition 2015

Rowan Williams, 2012

Rowan Williams has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: HB: 978-1408-18758-6

PB: 978-1472-92399-8

ePDF: 978-1408-18760-9

ePub: 978-1408-18759-3

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

Every archbishop, whether he likes it or not, faces the expectation that he will be some kind of commentator on the public issues of the day. He is, of course, doomed to fail in the eyes of most people. If he restricts himself to reflections heavily based on the Bible or tradition, what he says will be greeted as platitudinous or irrelevant. If he ventures into more obviously secular territory, he will be told that he has no particular expertise in sociology or economics or international affairs that would justify giving him a hearing. Reference to popular culture prompts disapproving noises about dumbing down; anything that looks like close academic analysis is of course incomprehensible and self-indulgent elitism. A focus on what many think are the traditional moral concerns of the Church (mostly to do with sexual ethics and family issues, though increasingly including end-of-life questions) reinforces the myth that Christians are interested in only the narrowest range of moral matters; an interest in other ethical questions invites the reproach that he is unwilling to affirm the obvious and sacrosanct principles of revealed faith and failing to Give a Lead.

Well, archbishops grow resilient, and sometimes even rebellious, in the face of all this. If it is true that religious commitment in general, and Christian faith in particular, are not a matter of vague philosophy but of unremitting challenge to what we think we know about human beings and their destiny, there is no reprieve from the task of working out how doctrine impacts on public life even if this entails the risk of venturing opinions in areas where expert observers vocally and very technically disagree with each other (such risk is not, after all, a wholly unknown phenomenon in the world of journalism). If it is true that the world depends entirely on the free gift of God, and that the direct act and presence of God has uniquely appeared in history in the shape of a human life two millennia ago, this has implications for how we think about that world and about human life. The risk of blundering into unforeseen complexities cant be avoided; and the best thing to hope for is that at least some of the inevitable mistakes may be interesting enough (or simply big enough) for someone else to work out better responses. The chapters printed here are the result of taking that sort of risk; and they are vulnerable to all the criticisms that I have already sketched. They are offered not as a compendium of political theology, but as a series of worked examples of trying to find the connecting points between various public questions and the fundamental beliefs about creation and salvation from which (I hope) Christians begin in thinking about anything at all.

That being said, in reading them over, I have found a number of unifying threads running through them, which may be the elements of something more like a broader theory about faith and the social order. We have been hearing quite a lot about the dangers of aggressive secularism, and the strident anti-Christian rhetoric of some well-known intellectuals is still a prominent feature of our society. But part of what I am trying to argue in several of these chapters is that our problem is not simply loud voices attacking faith (and certainly not persecution as some of the more highly-coloured apologetic claims). It is a set of confusions often shared between religious groups and their enemies. For example: it is often assumed that we all know what secularism or secularization means. But there is clearly more than one idea and process involved. Some very articulate debate goes on as to whether we are a secularised society in the way the term was used forty-odd years ago. If the only question is one of public respect for, and more or less active support of, traditional religious practices, it is obviously true that we have, in the UK as in most of Western Europe, moved further down the road already opening up in the 1960s, further away from the observance of public religious orthodoxies. But if the question is about the persistence of popular beliefs and habits, about assumptions concerning non-material powers and presences, we are a long way from being as disenchanted as some would like to think. Public ritual persists, reinventing itself energetically (the flowers at the site of a road accident). Call it what you like, but secular does not quite capture where we are.

And then, secularism as a term is pretty slippery. Ive suggested in various places that we need a distinction between procedural and programmatic secularism. Procedural secularism is the secularity proclaimed as a virtue by, for example, the government of India: a public policy which declines to give advantage or preference to any one religious body over others. It is the principle according to which the state as such defines its role as one of overseeing a variety of communities of religious conviction and, where necessary, assisting them to keep the peace together, without requiring any specific public confessional allegiance from its servants or guaranteeing any single community a legally favoured position against others. Programmatic secularism is something more like what is often seen (not always accurately) as the French paradigm, in which any and every public manifestation of any particular religious allegiance is to be ironed out so that everyone may share a clear public loyalty to the state unclouded by private convictions, and any signs of such private convictions are rigorously banned from public space.

The former kind of secularism or secularity poses no real problems to Christians; on the contrary, it is quite arguable that the phenomenon of the Christian Church itself is responsible for the distinction between communities that think of themselves as existing by licence of a sacred power, on the one hand, and political communities on the other. Early Christianity demystified the authority of the Empire and thus introduced a hugely complicating factor into European political life the idea of two distinct kinds of corporate loyalty, one of which may turn out to be more fundamental than the other.

Next page