Contents

Guide

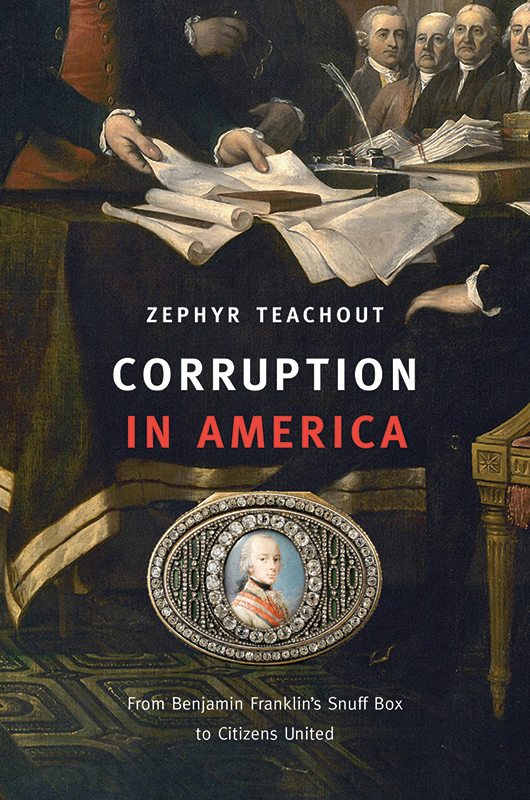

CORRUPTION

IN AMERICA

FROM BENJAMIN FRANKLINS SNUFF BOX

TO CITIZENS UNITED

ZEPHYR

TEACHOUT

Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2014

Copyright 2014 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Cover art: (background) Signing the Declaration of Independence, July 4th, 1776 (oil on canvas), John Trumbull. Bridgeman Art Library; (inset) Joseph tienne Blerzy 1775-1781. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Cover design: Graciela Galup

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Teachout, Zephyr.

Corruption in America : from Benjamin Franklins snuff box to Citizens United / Zephyr Teachout.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-05040-2 (alk. paper)

1. Political corruptionUnited StatesHistory. 2. Judicial corruptionUnited StatesHistory. 3. Political cultureUnited States. 4. United StatesPolitics and governmentMoral and ethical aspects. I. Title.

JK2249.T43 2014

364.1'3230973dc23 2014010417

To Aly, Waylon, Jed, Celia, Sargent,

Zoe, Dewey, Esme, Garth, Elise, and Elva,

my big-hearted, big-dreaming nieces and nephews

Contents

WHEN BENJAMIN FRANKLIN left Paris in 1785 after several years representing American interests in France, Louis XVI gave him a gorgeous parting gift. It was a portrait of King Louis, surrounded by 408 diamonds of a beautiful water set in two wreathed rows around the picture, and held in a golden case of a kind sometimes called a snuff box. The snuff box and portrait were worth as much as five times the value of other gifts given to diplomats. One historian has called it the most precious treasure in [Franklins] entire estate.

In Europe, gifts were socially required upon a diplomats departure. A valuable gift indicated a regents great favor and a job well done. But in the new United States, the snuff box signified danger. Such a luxurious present was perceived as having the potential to corrupt men like Franklin, and therefore it needed to be carefully managed. In Europe, in other words, the gift had positive associations of connection and graciousness; in the United States, it had negative associations of inappropriate attachments and dependencies. The snuff box stood for friendship or old world corruption, respect or bribery, depending on the perspective. For the Americans it was a symbol of seduction, dependency, luxury, and a European confusion about the proper relationship between politics, power and intimacy, and friendship.

According to an idiosyncratic anticorruption rule in the Articles of Confederation, Franklins present had to be approved by Congress, as did all gifts from foreign officials. By going through Congress, and requiring a congressional stamp, the direct relationship between the king and Franklin was complicated, made public, and partially reconstituted as a relationship between Congress and Franklin. It was no longer in the realm of private reciprocity and relationships, but was instead a regulated transaction. As I will describe later, this rule was initially taken out of the proposed Constitution but reinserted when some of the delegates to the convention worried that its absence threatened corruption.

The argument of this book is that the gifts rule embodies a particularly demanding notion of corruption that survived through most of American legal history. This conception of corruption is at the foundation of the architecture of our freedoms. Corruption, in the American tradition, does not just include blatant bribes and theft from the public till, but encompasses many situations where politicians and public institutions serve private interests at the publics expense. This idea of corruption jealously guards the public morality of the interactions between representatives of government and private parties, foreign parties, or other politicians.

The kings gift threatened this kind of corruption because it encouraged a positive tacit relationship between France and Franklin, built on diamonds. This could interfere with Franklins obligations to the country at large. No one charged the kings agent with explicit promises or threats. Instead, the worry was that intimate obligations that arise from large gifts could interfere with public commitments. Imagine anyone receiving a gift of 408 diamonds of the best water, and then, a few hours later, describing the gift giver in unattractive terms. The recipient would sound rude, ungrateful, and ungracious; we expect that gifts lead to some warmth and generosity toward the giver, if not official favors. Such private generosity, however, could violate the posture that the diplomat is supposed to have toward the leadership of the host countrythe allegiance ought be firmly to America. At the level of basic human intercourse, Franklin owed something to the king after receiving such a gift. These subtle sympathies threatened to corrupt Franklin because they could interfere with his responsibility to put the countrys interest first in his diplomatic judgments, and cloud his judgments about French actions. The concern held even though Franklin never planned to return to his post.

Americans started their experiment in self-government committed to expanding the scope of the actions that were called corrupt to encompass activities treated as noncorrupt in British and French cultures. Disappointed with Britain and Europe, Americans felt the need to constitute a political society with civic virtues and a deep commitment to representative responsiveness at the core. They enlisted law to help them do it, reclassifying noncorrupt, normal behaviors from Europe as corrupt behaviors in America. During the revolutionary period, the Americans not only created a new country but crafted a powerful political grammar. The concept of corruption in Franklins America drew on old traditions but augmented them and gave them power. He and his cohort believed that if you dont take care to support public emotional attachments of those in power, you cant build a representative government. When they spoke about corruption, the framers focused on the moral orientation of the citizens and representatives, the most essential building blocks of the republican state. Other political traditions focus on the more material problems of stability, anarchy, inequality, or violence. The American one focuses on the virtues of love for the public and the dangers of unrestrained self-interest. As I show throughout this book, this commitment to a broad view of corruption stayed largely the same in the courts for the countrys first 200 years.

Corruption is often equated with modern criminal bribery and extortion law, with kickback arrangements between mayors and contractors, and with officials who accept cash to change votes. But it plays a larger social and political role. The snuff box incident demonstrated the belief that temptation and influence work in indirect ways, and that corruption is not merely transactional, or quid pro quo, as it is sometimes called.

The law that governed the portrait in a snuff box also exemplifies the founders preference for a certain kind of anticorruption rule. These ruleswhich I call structural, or prophylacticcover innocent activity as well as insidious transactions. They stand in contrast to laws that require corrupt intent to convict. They work through changing incentives before the fact instead of punishing activity after the fact. In the gifts clause and dozens of other constitutional provisions, the framers built their bulwarks against corruption through structural rules. For instance, the residency requirement in the Constitution limits the freedom of people to run for Congress to where they live but is a worthwhile rule because it protectsimperfectly but practicallyagainst adventurers. Instead of requiring a jury to determine whether Franklin was