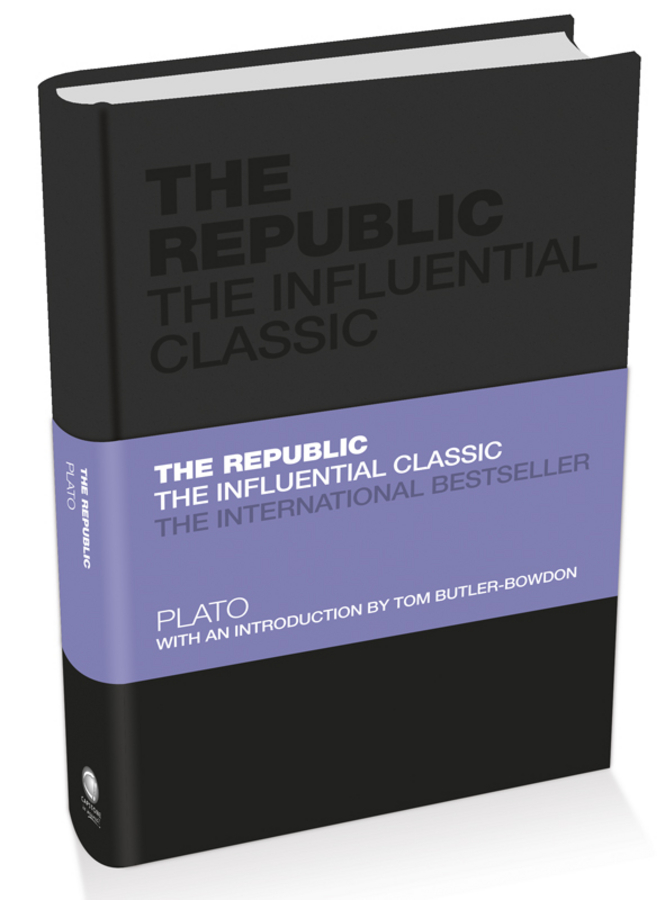

This edition first published 2012

Introduction copyright Tom Butler-Bowdon, 2012

The material for The Republic is based on the complete 1908 edition of The Republic of Plato , by Plato, translated by Benjamin Jowett, published by Clarendon: Oxford University Press, Oxford, and is now in the public domain. This edition is not sponsored or endorsed by, or otherwise affiliated with Benjamin Jowett, his family or heirs.

Registered office

Capstone Publishing Ltd. (A Wiley Company), John Wiley and Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com.

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-857-08313-5 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-857-08327-2 (ebk)

ISBN 978-0-857-08328-9 (ebk) ISBN 978-0-857-08329-6 (ebk)

Set in 9.5/13 pt ITC New Baskerville by Sparks www.sparkspublishing.com

An Introduction

by Tom Butler-Bowdon

Until kings are philosophers, or philosophers are kings, cities will never cease from ill: no, nor the human race; nor will our ideal polity ever come into being.

Despite being over 16 centuries old, The Republic is no dry political text, but still has much to say to the contemporary person about what it means to live the good life.

The word dikaiosun lies at the heart of the book. It does not have a direct English translation, but loosely means moral virtue, both at the personal and societal levels. In this Introduction we look at the basic meaning of justice for Plato in relation to the individual, before considering the characteristics of his ideal just state. Though it lays out his plans for a perfect society, we will see how Plato's most famous work can also be a guide for success as a person.

lies at the heart of the book. It does not have a direct English translation, but loosely means moral virtue, both at the personal and societal levels. In this Introduction we look at the basic meaning of justice for Plato in relation to the individual, before considering the characteristics of his ideal just state. Though it lays out his plans for a perfect society, we will see how Plato's most famous work can also be a guide for success as a person.

Plato's ideal state or society is characterized by wisdom, courage, self-discipline and justice, qualities that a well-balanced person should also develop. Conversely, his discussion of reason, spirit and desire (the three parts of the soul) shows how personal mental harmony is not just good for the individual, making them just, but good for their community too.

The Republic proceeds as a dialogue led by Socrates, who was Plato's teacher.

Across ten Books, Socrates responds with powerful logic to the questions and counter-arguments posed by Glaucon and Adeimantus, older brothers of Plato, and Polemarchus, whose home in Piraeus (the port of Athens) is where the dialogue takes place. Others include Thrasymachus, an orator, Polemarchus brothers Lysias and Euthydemus, and Cephalus, his father.

Part of the reason for The Republic's undying influence is that, despite being one of the great works of Western philosophy, it is still a relatively easy read, requiring no special knowledge. We use here the well-known translation by Benjamin Jowett, an Oxford don and master of classical texts.

Does it Pay to be Just?

The text begins with a discussion of the meaning of justice.

Cephalus argues that justice is simply telling the truth and making sure one's debts are paid. He will die a comparatively rich man, and says that one of the benefits of wealth is that one can die in peace, knowing all accounts are settled. But Socrates asks, is there not something more to truth and a good life than this?

Glaucon and Adeimantus make a case for injustice, saying that we can live to suit ourselves and get away with it, even prosper. Glaucon grants that justice is good in itself, but challenges Socrates to show how justice can be good at an individual level. Can the just person actually be happier than one who is not just? And if people can get away with it, surely they will act in unjust ways?

Glaucon evokes the story of Gyges and his golden ring. This magical ring gave Gyges the power to make himself invisible at will, and naturally enough, he uses it to do things that he could not get way with if he was visible. The story suggests that anyone with such a power would of course take what they want, sleep with whom they want, and so on, because they know they would never be detected. People only act justly when they fear they will be caught, Glaucon suggests, and have no interest in being good for its own sake.

Socrates response comes in some detail, but in essence it is this: doing the right thing is its own reward, since it brings the three parts of our soul (reason, spirit and desire) into harmony. Acting justly is not an optional extra, but the axis around which human existence must turn; life is meaningless if it lacks well-intentioned action. And while justice is an absolute necessity for the individual, it is also the central plank of a good state.

Socrates tries to convey the value of justice in his retelling of the myth of Er. This is the strange story of a man killed in battle whose body did not decay after his death. The reason is that the gods had anointed Er to be the one human who would be able to witness what happens after people die, and to return to the world afterwards to tell all of what he had seen.

Er recalled that after his death, he found himself in a meadow where souls gathered who had either just spent a life on earth, or who had just descended from heaven. They are meeting to choose their next incarnation, and are given lots to decide among their possible lives. Er describes the various choices that souls make, and their impulse or reason for making them. Having chosen, Er recalls, the souls would then drink from the river of Forgetfulness and then take form on Earth. Only Er is allowed not to drink. His body never having decomposed, after this vision of the afterlife he comes alive again while awaiting the flames of the funeral pyre.

lies at the heart of the book. It does not have a direct English translation, but loosely means moral virtue, both at the personal and societal levels. In this Introduction we look at the basic meaning of justice for Plato in relation to the individual, before considering the characteristics of his ideal just state. Though it lays out his plans for a perfect society, we will see how Plato's most famous work can also be a guide for success as a person.

lies at the heart of the book. It does not have a direct English translation, but loosely means moral virtue, both at the personal and societal levels. In this Introduction we look at the basic meaning of justice for Plato in relation to the individual, before considering the characteristics of his ideal just state. Though it lays out his plans for a perfect society, we will see how Plato's most famous work can also be a guide for success as a person.