To Bill, Nick and Haley

for their curiosity, patience and humor

Contents

Introduction

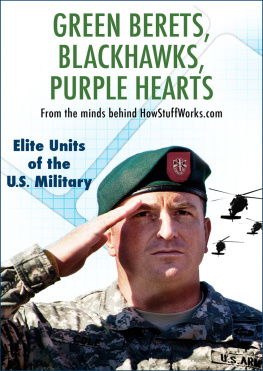

Pax Americana

A SWAT TEAM GUARDING ANTHONY ZINNI FACED OFF against Israeli snipers and tanks as the retired Marine Corps general climbed over the filthy barricades blocking Palestinian leader Yasir Arafats encircled compound in Ramallah, the West Bank. In April 2002, as President George W. Bushs special envoy, Zinni had secured approval from the Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, to meet with Arafat in the middle of an Israeli military offensive against the Palestinians. With water and electricity service cut off, the toilets inside the compound were overflowing and the stench was overwhelming. Arafat was spitting mad when Zinni arrived.

The Palestinians accused Zinni of conspiring with Israel to defeat Arafat. The Israelis accused him of cozying up to the Palestinians. In private, both sides admitted the same, sorry fact: There can be no military solution to the problem. Zinni was certain of that, too. You know, he groused later, as Palestinian suicide bombers and U.S. air strikes in Afghanistan competed for headlines, there is no military solution to terrorism, either.

Yet U.S. leaders have been turning more and more to the military to solve problems that are often, at their root, political and economic. This has become the American militarys mission and it has been going on for more than a decade without much public discussion or debate. Vanquishing terrorism is the latest example. U.S. diplomatic and economic efforts have lagged far behind the militarys in the campaign against terrorism, as they did in 2001 and 2002 in dealing with the Israeli-Palestinian impasse.

In the spring of 2002, Israeli military attacks on the Palestinians were threatening to accomplish what Osama bin Laden had not: turning the entire Muslim world against the United States. Arab allies were reshuffling their coalitions and threatening embargoes. Violent anti-American demonstrations were spreading around the world. Yet the worlds sole superpower was mustering only one retired general to pull the two sides toward the negotiating table. Zinni hoped he would be just a placeholder until someone with real clout in the administration, such as Secretary of State Colin Powell or President Bush himself, got involved.

But so far the president had paid only sporadic attention to the violence engulfing Israel and the Palestinian territories. From his ranch in Texas, Bush issued conflicting statements condemning terrorism, then Israeli aggression, then Arafat. He had hoped Israel and the Palestinians would sort this out on their own, without U.S. involvement. Bush rejected any suggestions that he pursue the style of personal diplomacy practiced by President Bill Clinton, just as he also rejected Clintons policy of global peacetime engagement. Too unfocused. Too open-ended.

At the Defense Department, the new unilateralists, led by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Deputy Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, and their chief policy guru, Richard Perle, chairman of the Defense Policy Board, had opposed sending Zinni to mediate. Tone deaf to the deep anti-American hatred welling up in the Muslim world, they opposed any action that would distract the administration from its ultimate goal: toppling Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein. Meanwhile, the Arab coalition so necessary to an anti-Iraq campaign withered.

Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and Perle, all civilian political appointees, faced off against a triumvirate of former military giants: Powell, a retired general and former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Zinni, a former commander of U.S. Central Command; and Powells deputy secretary of state, Richard Armitage, a former Navy SEAL whose short but intense military career had chiseled his rough-edged demeanor and ample physique. They just arent connected to the world, Zinni grunted dismissively of Rumsfeld et al. Thank God for the State Department and Colin Powellhes my hero. There are more military guys running things at the State Department than over at the Pentagon, he laughed. Perle! Ha! A paper cut was his biggest scrape.

At Powells urging, Bush had finally agreed to let Zinni step in and Zinni managed to convince the two sides to keep coming back to talk. When people become desperate, they need dispassionate leadership, he believed.

Zinni had pushed the same level of U.S. involvement throughout his time at Central Command, hammering Clintons team to let him bring his resources to bear in crazy Yemen, forsaken Pakistan, and authoritarian Uzbekistan. He would have gone to Afghanistan and Iran, too, had his bosses allowed itanything to keep these failed and nearly failed states from straying too far from the norms that kept the planet from self-destructing.

Zinnis interest in diplomacy struck him as part of an historical continuum. By doffing the uniform to become secretary of state and pushing his unpopular Marshall Plan through Washington, Gen. George Marshall had achieved the rebuilding of Europe after World War II. Gen. Douglas MacArthur had done much the same for postwar Japan. Marshall, reflecting on the conditions that gave rise to Nazism, warned more than once that the United States courted disaster if it again fell into a state of disinterested weakness and failed to lead Europes postwar economic and political reconstruction. Zinni saw Powell as a modern-day Marshall. Having championed the use of overwhelming military force at the outset of any war (in what came to be known as the Powell Doctrine), Powell was now arguing for overwhelming economic and political force to settle a rattled postSeptember 11 world.

But Bush was resisting. Both he and President Clinton before him seemed reluctant to leverage the unprecedented stature that the United States had acquired at the end of the Cold War as an empire without rival. As a consequence, both presidents, and the Congresses that governed with them, failed to capitalize on this historic pre-eminence to lead a messy world toward a more stable peace. It was easier to call up the military for a quick fix.

By 2002, Americas military was unmatched by factors of ten. Its Special Operations Forces and the paramilitary teams of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had adapted fairly well to the asymmetric warfare of terrorists and their armies of supporters in Afghanistan. Their tactical offensives seemed likely to kill off Al Qaeda and maybe even capture Osama bin Laden. Yet despite their superiority, they could not stamp out terrorism; the seeds of that problem were planted in the soil of despair, isolation, and zealotry. Terrorisms ultimate defeat would not come on the battlefield at the hands of soldiers. Neither President Bush nor his armed forces had a strategy for that campaign.

Long before September 11, the U.S. government had grown increasingly dependent on its military to carry out its foreign affairs. The shift was incremental, little noticed, de facto. It did not even qualify as an approach. The military simply filled a vacuum left by an indecisive White House, an atrophied State Department, and a distracted Congress. After September 11, however, the trend accelerated dramatically with the war in Afghanistan and the likelihood of U.S. military operations elsewhere. Without a doubt, U.S.-sponsored political reform abroad is being eclipsed by new military pacts focusing on anti-terrorism and intelligence-sharing.

Next page