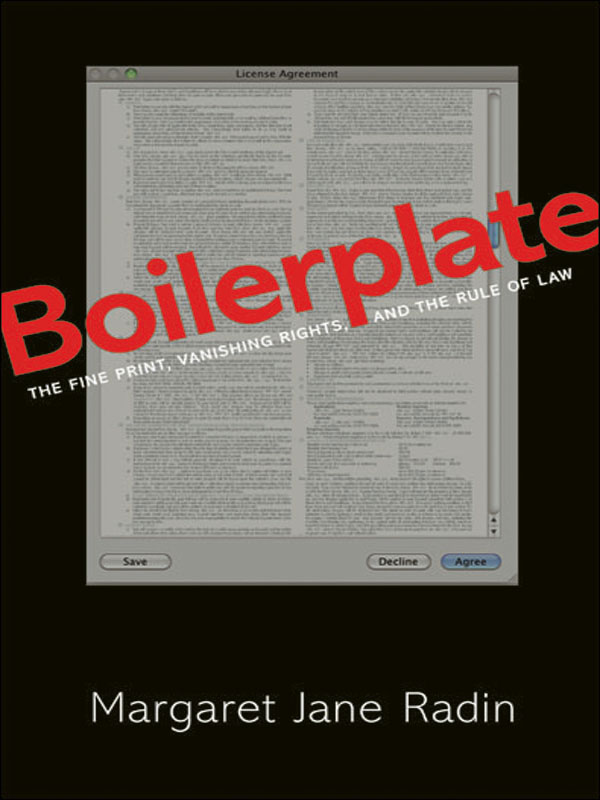

Boilerplate

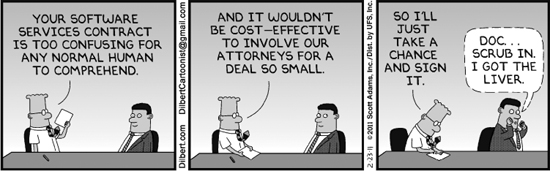

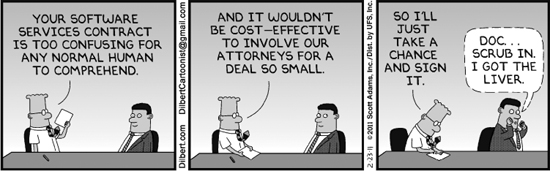

DILBERT 2011 Scott Adams. Used by permission of UNIVERSAL UCLICK. All rights reserved.

Boilerplate

The Fine Print, Vanishing Rights, and the Rule of Law

Margaret Jane Radin

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration and design

by Marcella Engel Roberts

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Radin, Margaret Jane.

Boilerplate : the fine print, vanishing rights, and the rule of law / Margaret Jane Radin.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-15533-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-691-15533-X (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Standardized terms of contractUnited States. I. Title.

KF808.R25 2012

346.73022dc23

2012017290

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

In memory of

C. Edwin Baker

(19472009)

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T HIS BOOK HAS BEEN a number of years in development. It probably began when I first started teaching contract law at Stanford Law School in the late 1990s, and, of course, noticed that boilerplate fits very uneasily with contract theory. So my first acknowledgment should be to Stanford, and to former Dean Paul Brest, for allowing me to switch from property to contract at that point in my career, and for underwriting the research and writing I did beginning in 2000. Thanks for institutional support of my research is also due to Princeton University, where I was the inaugural Microsoft Fellow in Law and Public Affairs in 20062007; at that point I began work on the book that eventually metamorphosed into this one. The institutional support of the University of Michigan from 2007 onward has been indispensable; thanks especially to the Wolfson and Cook funds, and to Dean Evan Caminker and Associate Dean Mark West.

As it developed, this project benefited from numerous workshops at other schools and the active engagement of workshop participants. Thanks to workshop participants at Duke University, Cornell University, the University of Wisconsin, and the University of Michigan, and to the Georgetown Contract and Promise Workshop organized by Gregory Klass. Thanks to Capital University Law School for inviting me to deliver the 2011 Sullivan Lecture. Very special thanks to the University of Toronto and to Dean Mayo Moran for sponsoring an all-day workshop on a version of this book in March 2011, for which many faculty members read the manuscript and presented their views and critiques. I am grateful for such extraordinary colleagueship. I am also grateful to the Centre For Innovation Law and Policy at the University of Toronto for inviting me to deliver the Grafstein Lecture in March of 2011.

A great many colleagues have read all or portions of the drafts of this book and significantly improved it. I owe special recognition to the generosity of Michael Trebilcock, who read the entire manuscript in at least two and perhaps three stages of development, and wrote astute comments on many of its pages. For reading through the manuscript and offering helpful critiques and suggestions, thanks also to the ideal colleagueship of Ariel Katz, Abraham Drassinower, Catherine Valcke, Bruce Chapman, Stephen Waddams, Peter Benson, Jennifer Nedelsky, Arthur Ripstein, Brian Langille, Lisa Austin, Ian Lee, Mariana Mota Prado, Simon Stern, Denise Raume, John Pottow, Bruce Frier, Aditi Bagchi, and Ethan Leib. Thanks to Stephen Poppel, an amateur musician like me, an acquaintance from summer music camp, who read the entire manuscript in an early version and made numerous suggestions for how to make it suitable for nonlawyers to read.

Thanks to Jay Feinman, Arti Rai, Andrew Gold, and Jeffrey Ferriell for commentary on portions of this project presented at workshops and lectures. I also appreciate suggestions made by Andrew Coan, Kim Krawiec, Bernadette Meyler, Edward Parson, Jill Horwitz, Scott Hershovitz, Robert Hillman, Daniel Schwarcz, Brian Bix, and Daniel Markovits. Special thanks to advocates who offered advice from the field: Paul Bland, John Richard, David Arkush, and Theresa Amato. I am very much indebted to the talented and diligent law students who have worked on this project as research assistants: Stephen Woodcock, Eli Best, Rory Wellever, Bryn R. Pallesen, Aqsa Mahmud, James Ray Mangum, Ankit Bahri, Jennifer Tanaka, John Patrick Clayton, and especially Meera El-Farhan and Shannon Leitner, both eleventh-hour lifesavers. Finally, thanks to Michigan Law Review veterans Adam Teitelbaum and Charles Weikel, who checked the citations on all the notes. Thank you all. I hope I have not forgotten anyone.

Chuck Myers, my acquisitions editor at Princeton Press, contributed invaluable expertise and critical help. He is very good at what he does! Thanks to Wayland J. Radin for the photos and for help in preparing the manuscript for submission. Finally, thanks to my husband, Phillip Coonce, thanks that I really cannot write with adequate eloquence. Phils personal support has been more than the reasonable person could ever have wished for. In addition, he read the manuscript twice from cover to cover, and he improved it significantly with comments ranging from small noodges on almost every page to overarching big questions.

This book is dedicated to the memory of C. Edwin Baker, my close friend for more than thirty years and my worst (that is, my best) critic for that long. I have no doubt that if Ed were still here, his gracious and tenacious critique would have made this a better book.

Margaret Jane Radin

Ann Arbor, Michigan

December 2011

PROLOGUE: WORLD A (AGREEMENT) AND WORLD B (BOILERPLATE)

A greement, the traditional basis of contract (an invented story):

Sally says to John, I really like your bicycle. Will you sell it to me for $100? John says, Well, I couldnt part with it for $100, but how about $125? Sally says, OK, I really do like it, so how about $120? John says, Its a deal. Ill go get the bike. Then Sally hands over $120.

But John never delivers the bike. After John fails to perform his side of the bargain, Sally can bring John to court in a place convenient for her and ask that John be found in breach of contract. If the court finds that John breached a contract with Sally, John will be ordered to compensate Sally. Probably John will be ordered to pay Sally whatever amount she has lost by not receiving the bicycle, which could include not only the amount it would cost her to buy an equivalent bicycle from someone else, but whatever amounts she has lost as a consequence of the broken contract, such as being unable to deliver her packages of handmade chocolates to her customers, and having her customers go to other chocolate sellers.

B oilerplate, our nonideal contract in practice (stories based on real cases):

Arbitration Clause: Garrit S., age eleven, a boy who cared deeply about animals, went to Africa with his mother on a fantasy safari vacation. Before it booked the trip, the tour company had Garrits mother sign a form. The form waived (cancelled) the right to sue the company for injury to either the mother or the son. Instead, the form said, if there was any complaint against the company, the mother would be limited to arbitration. Such a waiver of legal

Next page