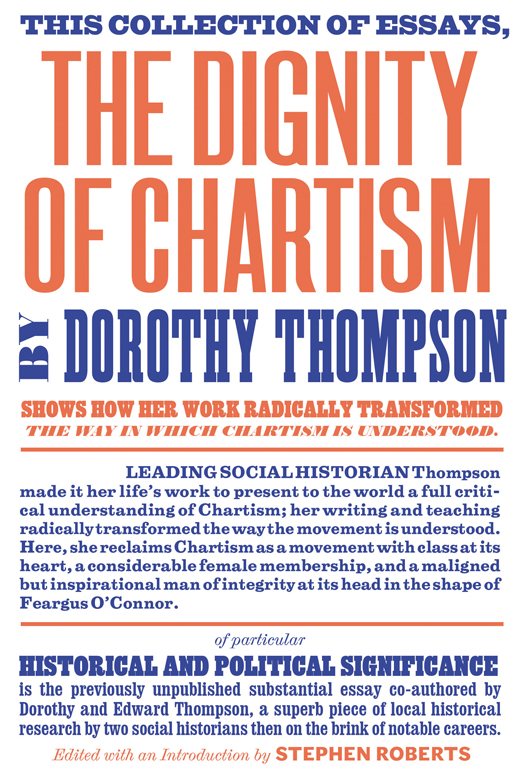

THE DIGNITY

OF CHARTISM:

ESSAYS BY

DOROTHY THOMPSON

Edited by Stephen Roberts

First published by Verso 2015

Dorothy Thompson 2015

Introduction and prefaces Stephen Roberts 2015

The publisher and editor gratefully acknowledge the journals that published earlier versions of the essays collected here: Amateur Historian, Bulletin of the Society for the Study of Labour History, Cycnos, the Encyclopedia of the 1848 Revolutions, History Workshop Journal, Irish Democrat, Labour History Review, New Reasoner, Times Higher Education and Times Literary Supplement. The date and place of original publication are acknowledged in a footnote at the start of each chapter.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-849-6 (PB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-848-9 (HB)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-851-9 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-850-2 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thompson, Dorothy, 19232011.

[Essays. Selections]

The dignity of chartism : essays by Dorothy Thompson / edited by

Stephen Roberts.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-78168-849-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-78168-848-9

(hardback : alk. paper)

1. Chartism History. 2. Labor movement Great Britain History.

3. Working-class Great Britain History. I. Roberts, Stephen. II. Title.

HD8396.T452 2015

322.20941 dc23

2014043269

Typeset in Sabon by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in the US by Maple Press

To the memory of Charlie Williams

CONTENTS

I am indebted to Kate Thompson, who gave permission for the work of her parents to be collected together in this volume and who also patiently answered my numerous requests for assistance. Ben and Mark Thompson both read the introduction, and gave me great help with points of detail. At the outset Kate Tiller discussed this project with me over lunch in Oxford, and, as it came together, offered advice and assistance. Owen Ashton, on several occasions, talked over my plan of action, and also read one section of the book. Bob Fyson, Robert Hall and Ted Royle agreed to read the other sections of the book, and their feedback was much appreciated. I am grateful to Sheila Rowbotham, with whom I enjoyed two long conversations one in a black cab and the other on a train about Dorothy and Edward Thompson. I have also profitably discussed sections of this book with Terry Brotherstone, John McIlroy and Malcolm Chase. In their different ways Penny Corfield, Jim Epstein, Julian Harber, Patrick Joyce, Bob Knecht and Bryan D. Palmer have been most supportive. Richard Brown, Margot Finn, John Hargreaves, Antony Taylor, Alex Tyrrell and Cal Winslow responded helpfully to my queries. I am very grateful to Debbie Roberts and Staffordshire University Library for the help and support I received. Pete Bounous and Lewis Jones provided essential technical assistance. My thanks, too, to Sebastian Budgen and Mark Martin at Verso for their expert advice and for reassurance when it was needed.

I would like to acknowledge the support of a number of people who helped clear the way and enabled all of this work to appear between the covers of one volume: Paul Corthorn; Malcolm Chase; Kevin Towndrow; James Chastain; Karen Shook; Alan Crosby and the British Association for Local History; Michael Carty; Terry Brotherstone, Anna Clark and Kevin Whelan; Peter Burns; the Editorial Collective of History Workshop Journal; and Christian Gutleben. I have indicated the original place of publication in the first footnote of each essay.

This book is dedicated to the memory of my great-uncle, Charlie Williams. He embraced such causes as communism and vegetarianism, and was arrested on a fabricated charge of striking a police officer when local Communists disrupted a meeting in the Central Hall in Birmingham in 1923. His espousal of the Communist cause cost him his job at Cadburys, and, at the outbreak of war in 1939, he only just managed to get home from the Soviet Union. I waited thirty years to tell Dorothy Thompson his story. It proved to be the final conversation we had.

Dorothy Thompsons essays and reviews on Chartism were published in many different places. My aim in putting together this collection has been to make her miscellaneous writings on this subject easily accessible. Inevitably, in a collection of pieces written over a period of years and for a range of publications, there will be some overlap and some points that are no longer applicable. Consequently, I have made some deletions, though these are not extensive. To help the reader, I have augmented the footnotes, identifying figures mentioned in the essays and pointing to further reading. The unpublished essay on Halifax Chartism was not completely finished or at more than 30,000 words edited. To make it a more suitable length for inclusion in this collection, I have condensed some of the more drawn-out passages and quotations as well as reducing the number of footnotes. The original essay can be read on Ben Thompsons website at www.tufsoft.com/pdf/HalifaxChartists.pdf. Except in passages where Edward Thompson features, I have referred to Dorothy Thompson by her surname in this book.

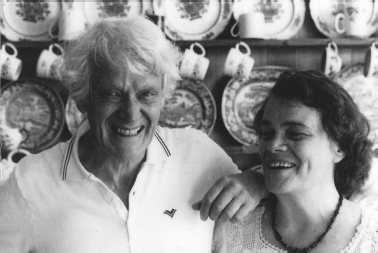

Edward and Dorothy Thompson at home at Wick Episcopi, near Worcester, mid-1980s.

INTRODUCTION

RETHINKING THE CHARTIST

MOVEMENT: DOROTHY

THOMPSON (19232011).

BY STEPHEN ROBERTS

Dorothy Thompson was the pre-eminent historian of Chartism.

Dorothy Katherine Gane Towers was born in Greenwich, south London, on 30 October 1923. It was her paternal grandfather, a shoemaker who worked part-time in music halls, who had settled in the capital. Her parents, Reginald and Katharine, were both professional musicians who met at the Royal Academy of Music, though most of their income came from running shops which sold musical instruments (and later televisions) and teaching. They were both supporters (but not members) of the Labour Party, and Dorothy and her brothers Tom, Glen and Alan grew up in a household where politics and family history were regularly discussed and where the Daily Herald and Reynoldss News were taken: she recalled Tom sending the contents of his money box to the miners in 1926. Her brother Tom was not in robust health and so the family moved to Kent, first to the agricultural village of Keston and then to Bromley. In Keston the family lived in a four-room cottage lit by oil lamps and candles, soaked themselves in a zinc bath in front of the fire and visited an outside lavatory that was not at first connected to the mains water supply. I could read by the time I was three, Thompson later recalled, and cannot remember ever facing a page of print I couldnt understand. In her first Summer holidays were spent either accompanying her mother to visit relations in France, or with her maternal grandmother in Gloucestershire (a phrase Thompson adopted from her grandmother was Gloucestershire generosity, meaning to pass on an unwanted gift).