Contents

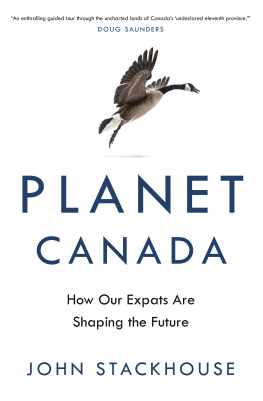

ALSO BY DOUG SAUNDERS

Arrival City

The Myth of the Muslim Tide

To Griff and Maud, twenty-first century Canadians

VINTAGE CANADA EDITION, 2019

Copyright 2017 Doug Saunders

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Published by Vintage Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, in 2019. Originally published in hardcover by Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, in 2017. Distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage Canada with colophon is a registered trademark.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Maximum Canada / Doug Saunders.

ISBN9780735273108

Ebook ISBN9780735273115

1. CanadaPopulationForecasting. 2. CanadaSocial conditions21st century. 3. CanadaEconomic conditions21st century. I. Title.

HB3529.S38 2018304.60971C2017-901762-4

Cover design: Jennifer Lum

Cover image Arthimedes/Shutterstock.com

Text design: Andrew Roberts

v5.3.2

a

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

The War against the Outside

Around midnight on an early winter evening one hundred and eighty years ago, my grandmothers great-grandmother stood in fury as a crowd of armed rebels forced their way inside her Brantford house, demanding the rifles and pistols that she and her Welsh-born barrister husband, William, had spent the day hiding. The couple had armed themselves that autumn, and William had worked to organize a local militia, in the certain belief that they would soon be joining an all-out civil war over the size, composition and purpose of Canada.

Twelve of them came down to us in the middle of the night demanding armsthey had each suspended to their sides swords and rifles. They searched the house but William, being a strong Tory, had the precaution to hide his guns and pistols and etc., Catherine Lloyd-Jones, then thirty-six and a mother of three, wrote her mother in England. They left disappointed but told us to beware of the rabble. As the men departed in frustration, William yelled after them that he would be joining the fight, but not on their side. The couple knew these rebels: Canadian men from the nearby village of Scotland, men who had resided in Canada far longer than they had. But Catherine denounced them and their fellow rebels as Americans, for she and other Tories saw their expansive and democratic ideas, their support of public education and open borders and elected governments, as treasonous and foreign.

I then felt alarmed and rather dreaded the consequences of refusing them arms, Catherine wrote. Fancy me close to Williams elbow, pale as death in my night dress covered with a cloakI think I could almost have fired at them myself. They spent the next several weeks sleeping fully dressed with weapons at their side, prepared to flee the house, pistols in hand, and join the coming fight.

What a country this is, my dear Mother, Catherine lamented to her overseas family. This is to come to nothing but warand civil war the worst of allbeing in danger of being shot by our neighbours. People are in danger of their lives unless armed with their pistols even to go a mile from their own home. Little did we anticipate a bloody war which will eventually take place.

Catherines fears were only partially realized. Civil violence, rifle battles and a serious national crisis did ensue, but the war that took place in the days after Catherines letter, today known as the 1837 rebellions, would not prove as bloody or as lengthy as my ancestors feared. The pro-democracy uprisings in Upper and Lower Canada, including the events Catherine and William experienced in Brantford (an abortive effort by settlers around Brantford and Hamilton, led by prominent Reform politician Charles Duncombe, to lend their support to the Toronto rebellion), would be crushed by colonial troops in a few weeks. The Reformers who launched and fought in the rebellion were tried and transported to Australia, forced to flee to the United States or executed. The Lloyd-Joneses, one of the few regime-supporting Tory families in their region, would keep their handsome house outside Brantford. Their son Thomas would turn his fathers volunteer militia, the Burford Troop of Volunteer Cavalry, into a standing regimental division designed to protect Upper Canadas closed colonial regime for the rest of the century.

What Catherine had in mind was the far larger but less violent civil war that had been underway as long as shed lived in Upper Canada, one that had been launched by Canadas British occupiers almost the moment the War of 1812 had ended a quarter-century earlier. It was a war to limit British North Americas ambitions, its size and its purpose. While the enemies were often described as Americans, all of them were in fact long-standing residents and subjects of the Canadian colonies. The border with the United States had been slammed shut to migration after 1815, so that the U.S.-born families of Canada (who until the 1830s were the majority of Upper Canadas population) had lived there much longer than most British-born settlers and had a greater claim to being real Canadians.

The colonial rulers did not hesitate to call this clash of loyalties and visions a war and to specify what they were fighting. Sir Francis Bond Head, the Tory lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, had urged British Anglicans (among them Catherine and William) to emigrate to the colony after 1815 by telling them theyd be soldiers in a moral warbetween those who were for British institutions, against those who were for soiling the empire by the introduction of democracy.

The conflict involved much more than democracy versus British institutions, though. It was an all-out struggle to ensure that the emerging Canada would be a closed, ethnically homogeneous colony whose political and economic function would be limited to the provision of raw materials to the imperial capital, and whose population would be restricted mainly to small-hold farming. This was a vastly different place from the pre-1812 Canada. Though tiny and sparse, that earlier Canada had been defined by an ambiguous and open border, diverse immigration and a free-flowing trade in goods, people and ideas with the newborn United Statesall of which were now forbidden. This was a war against expansion and openness.

Catherine and William saw their ideas triumph (though William would die eight years later when he fell from a wagon). Canadas border would remain closed and tariff-walled for decades. Its immigration policies would allow only a certain sort of British person; its economy would remain colonial, rural and resource-based. This victory would exact a heavy and lasting cost on Canada. For the rest of the nineteenth century, and much of the twentieth, the new country would fail to attract people, despite constant efforts to do so. Underpopulation would become a constant and lasting problem.