Contents

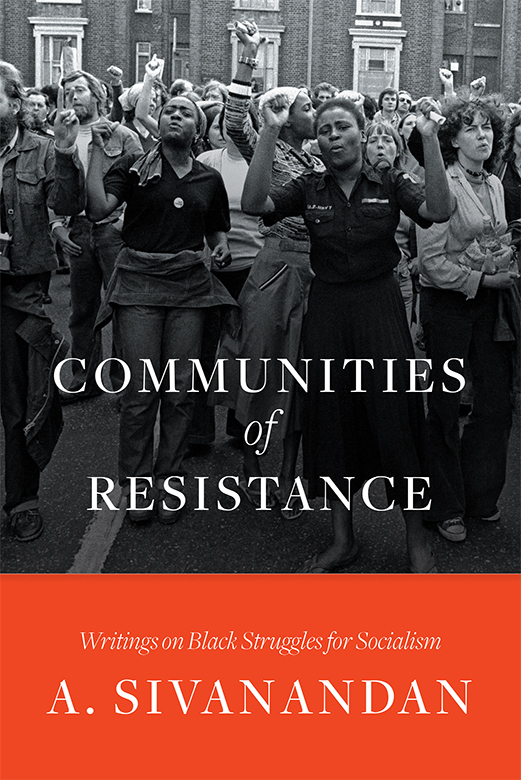

Communities of Resistance

Communities of Resistance

Writings on Black Struggles for Socialism

A. SIVANANDAN

Foreword by Gary Younge

With an Introduction by Arun Kundnani

This edition first published by Verso 2019

First published by Verso 1990

A. Sivanandan 1990, 2019

Foreword Gary Younge 2019

Introduction Arun Kundnani 2019

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-256-7

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-457-8 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-458-5 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Has Cataloged the

First Edition of this Book as Follows:

Sivanandan, Ambalavaner

Communities of resistance : writings on Black struggles for socialism / A. Sivanandan.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-86091-296-5. ISBN 0-86091-514-X (pbk.)

1. Blacks Great Britain Politics and government. 2. Blacks Great Britain Social conditions. 3. Socialism Developing countries. 4. Socialism Great Britain. 5. Racism Great Britain.

I. Title.

DA125.A1S57 1990

305.896041 dc20

Typeset in Baskerville

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

For Jabe beyond owing

Contents

Foreword

by Gary Younge

In 1958, Ambalavaner Sivanandan dressed up as a policeman in his native Sri Lanka and brandished a gun without any bullets, in order to save members of his Tamil family from a Sinhalese mob. Later that year Siva, as he was known, left what was then Ceylon and came to Britain, arriving only to witness the anti-black race riots in Notting Hill. I knew then I was black, he later wrote. I could no longer stand on the sidelines: race was a problem that affected me directly. I had to find a way of making some sort of contribution to the improvement of society.

In his position as the director of the Institute of Race Relations for forty years, from 1973 to 2013, and the editor of its journal, Race & Class, Siva remained true to that mission; a tireless and eloquent voice explaining the connections between race, class, imperialism and colonialism.

Siva highlighted in what was a radical position at the time that it was not the presence of black people that created racism, but the refusal of the British state to evolve into a multiracial society. His writing on state and institutional racism was key to ideas that later entered the mainstream with the publication of the Macpherson Report in 1999. As director of what became a radical think tank, he focused his advocacy on the most excluded and those affected by the most vicious manifestations of racism. There are two racisms: the racism that discriminates and the racism that kills, he wrote. To bemused would-be funders who asked to whom IRR was speaking, he replied, We do not speak to, but from.

Siva had many such phrases, encapsulating complex ideas, that challenged simplistic assumptions. Others included: We are here because you were there (relating to post-colonial migration); If those who have do not give, those who havent must take; and The personal is not political, the political is personal.

The latter illustrated his growing frustration with the solipsism of emerging identity politics, particularly among what he saw as a more well-heeled, younger generation of black intellectuals, who he felt were reluctant to engage with issues of class even though it was the struggles of the black working class that had paved the way for them. The people who made this mobility possible were those who took to the streets, he once told me. But they did not benefit.

It was Siva who renamed Race, the IRRs journal, Race & Class, positioning it to become a leading voice for radical race politics, with writers such as Cedric Robinson, Edward Said, John Berger, Angela Davis and Noam Chomsky. It carried his own ground-breaking essays, including pieces in this collection: the scathing polemic against an attempt to reorient the Left away from class in All That Melts into Air Is Solid: The Hokum of New Times; his essay on anti-racist shortcuts peddled by local authorities, RAT and the Degradation of Black Struggle; New Circuits of Imperialism, which laid out how new technology would displace labour and liberate capital; and Sri Lanka: A Case Study on race, class and the state in post-colonial societies.

It was this unrelenting attention to the connections and contradictions between race and class, the need to understand how they engage and intersect, the compulsion not to leave them in isolation but to view them in their national, international and local context which drew me and many others towards him. For he was a trusted advocate who exercised his erudition and talents in the interests of those he held most dear, the black, the brown, the poor and in particular the black and the brown who were poor and militant.

He died in 2018 but lives on in the ideas he has bequeathed us that will, hopefully, frame the struggles that will bend the world to our will one day. In those efforts its crucial that we say his name and disseminate his ideas so that others may hear and seek out his wisdom. In the words of Alice Walker, A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children and, if necessary, bone by bone.

Introduction

by Arun Kundnani

A. Sivanandan was the foremost intellectual of the black working-class movement in Britain during its insurgent heyday from the late 1960s to the late 1980s. The essays collected here, written between 1982 and 1990, and originally published as a collection in 1990, constitute his analysis of the means by which that movement was disaggregated, undermined and muted. To read them today is to be simultaneously confronted with connections and discontinuities between then and now, victories that might have been and losses forgotten, the familiar and the strange. By the mid-1980s, the dominance of what we would now call neoliberalism had become an unavoidable and overwhelming global political reality one that has remained with us to the present day. At the same time, the older traditions of black and working-class struggle in Britain still had enough life in them to provide the seeds of an analysis of the newly emerging political terrain. These essays, then, analyse structures of domination and exploitation we still live with from the perspective of an earlier, insurgent phase of activism and that is their great value for us today.

The son of a rural postal clerk from the hinterland of a minor colonial territory, Sivanandan fled Sri Lanka after the anti-Tamil pogroms of 1958 and arrived in London a refugee. The experiences of postcolonial ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka and racism in Britain became the twin poles around which he weaved his politics, his double baptism of fire (). One inscribed in his soul the dangers of ethnic separatism, the other brought home the need for a race politics relatively independent of the existing British labour movement. Socialism was the goal, but it was a socialism blackened by the experiences of racism and imperialism.