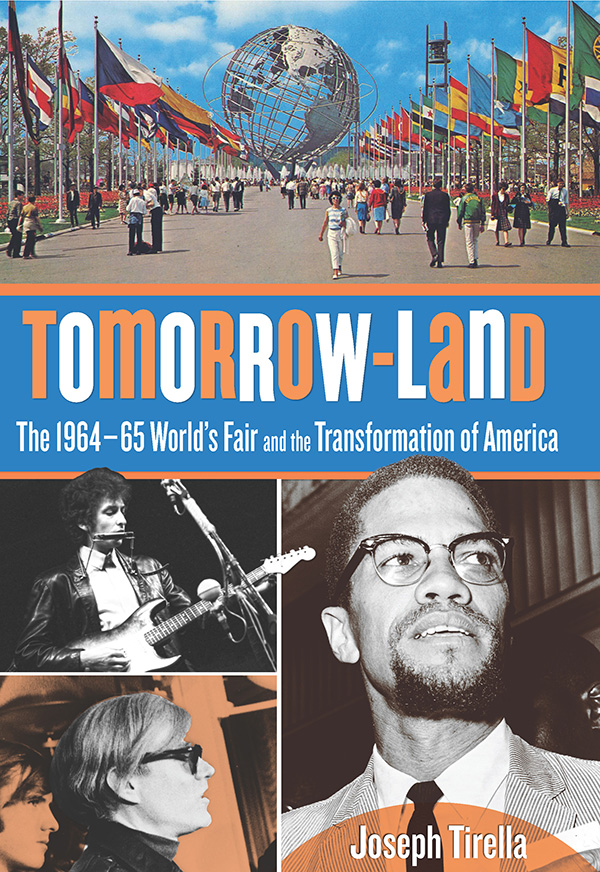

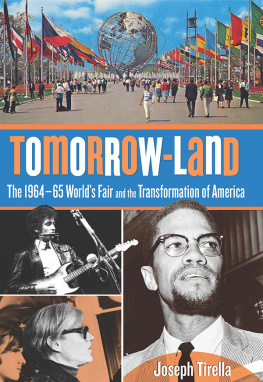

TOMORROW-LAND

THE 196465 WORLDS FAIR AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA

JOSEPH TIRELLA

For Kelly, Leo & Zo

Copyright 2014 by Joseph Tirella

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project editors: Meredith Dias and Lauren Brancato

Layout artist: Sue Murray

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-1-4930-0332-7

Contents

Part One

The Greatest Single Event in History

The basic purpose of the Fair is to help achieve Peace Through Understanding, that is, to assist in educating the peoples of the world as to the interdependence of nations and the need for universal and lasting peace.

New York Worlds Fair 196465 Progress Report from Robert Moses, January 16, 1961

It is insane that two men, sitting on opposite sides of the world, should be able to decide to bring an end to civilization.

President John F. Kennedy, October 1962

Standing outside the Worlds Fair Administration Building in Flushing Meadow Park in the late morning cold of December 14, 1962, Robert Moses knew that nearly three years of work were about to pay off. Since May 1960, when he assumed the presidency of the Worlds Fair Corporation in a sleight-of-hand coup dtat, he had taken charge of every aspect of the upcoming 196465 Worlds Fair; no detail was too insignificant for his attention. Now, after much political intrigue and maneuvering, the most powerful man in the free world, President John F. Kennedy, was coming to Queens to bestow his personal blessing on Moses Fair by participating in the ground-breaking ceremony for the $17 million United States Federal Pavilion.

New York Citys Master Builder had worked tirelessly to enact his grand schemes for what he called the Olympics of Progress. Moses knew that Worlds Fairs were historic opportunities for cities and nations to enhance their images on a global stage. Londons Great Exhibition of 1851 showcased the famed Crystal Palacean immense structure of metal and glass that illustrated Victorian Englands industrial mightand was opened by the Queen herself; Pariss Exposition Universelle of 1889 gave the world the Eiffel Tower; and in 1893 the United States hosted its second Worlds Fair in Chicago (Philadelphia had hosted a smaller fair in 1876), one that demonstrated Americas maturity as a nation. The Fairs planners transformed part of Chicago into the neoclassical White City (and introduced a ride that would become a staple of fairs the world over: the Ferris wheel). In 1904 St. Louis hosted a Worlds Fair that marked the debut of a new form of communication, the first wireless telegraph machine, and more prosaically, introduced a new way of eating ice creamthe ice-cream cone.

However, it was New Yorks 193940 Worlds Fair, which a younger Moses had worked on, with its dramatic, geometric-shaped sculpturesthe Trylon and the Perispherethat offered Depression-era America a glimpse of the World of Tomorrow, a futuristic fantasy world of skyscrapers, superhighways, and televisions that, like economic prosperity, was just around the corner.

Now, in the beginning of the 1960s, Moses and his team had spent years negotiating with Washington, DC, politicos for federal funding (often arousing more ill will than good) while playing diplomatic chess matches with foreign bureaucrats. He also initiated colossal plans for the reconstruction of major New York City thoroughfares such as the Van Wyck Expressway and the Grand Central Parkway, both of which would lead millions of Fairgoers to his exhibition. As usual, Moses, the holder of a dozen unelected positions, including New York City Parks Commissioner, chairman of the City Planning Commission, and chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, disrupted the streets of New York as he saw fit, with little regard for the impact his plans had on the lives of its citizens. You have to break eggs to make an omelet was his standard reply to his increasingly vocal critics. As was his style, when either obstacles or opponents got in his way, he outmaneuvered or, if necessary, ran roughshod over them.

Moses had spent much of the previous forty years molding and transforming New York to fit his own personal vision of a modern metropolis. He built a vast network of highways, bridges, parkways, public pools, playgrounds, beaches, and state power projects while clearing huge tracts of land with federal fundssometimes destroying neighborhoods in the process. Casting a shadow over his beloved New York at least as large as the Manhattan skyline, Moses served as an unelected government employee under seven governors and six mayors, and for nearly half a century was an inevitable fact of life in Gotham, as much as death, taxes, and rush hour traffic.

After Kennedys motorcade pulled up to the building, the president stepped out of his limousine and greeted Moses, with whom he had maintained a cordial connection since his days as a Massachusetts senator. The youthful Kennedy, who had removed his heavy overcoat despite the frosty chill, was a striking contrast to the graying bureaucrats who had gathered to meet him, like the Fairs US commissioner, Norman K. Winston, a real estate developer and close ally of Moses, or the dour mayor of New York, Robert F. Wagner Jr. described by Norman Mailer as plump, groomed, blank in the pages of Esquire .

Regardless of his hosts combative and autocratic style, Kennedy knew that Moses got things done. Certainly Kennedy, ever the political pragmatist, admired Moses ability to surviveand dominateNew Yorks cutthroat political system. Side by side on the stage set up for the ground-breaking, surrounded by the four-and-a-half-acre construction site of the US Federal Pavilion, they now sat: On the left was Kennedy, the only man on the stage not wearing a fedora or an overcoat, or apparently under the age of fifty; his youthful image and forward-looking New Frontier policies seemed to embody the hopeful idealism that was still at the heart of American life. Beside him, the elderly Moses personified bare-knuckled power as New Yorks Machiavellian Master Builder.

When it was Kennedys turn to speak, he rose to a podium bearing the presidential seal and delivered a short speech that was a peaceful call to arms. As his words turned to frosty breaths in the cold December air, the president reminded the crowd that the upcoming Worlds Fair represented a chance for us in 1964 to show seventy-five million people... from all over the world, what kind of a people we are and what kind of a country we are... and what is coming in the future. That is what a Worlds Fair should be about and the theme of this Worlds FairPeace Through Understandingis most appropriate in these years of the Sixties. I want the people of the world to visit this Fair and all the various exhibits of our American industrial companies and the foreign companies, who are most welcome, and to come to the American exhibitthe exhibit of the United Statesand see what we have accomplished through a system of freedom.

Kennedys trip to the Fairgrounds was a welcome respite. The Fairs Peace Through Understanding theme was more than just an idealistic slogan to the young president. Two months earlier, the Cold War had almost exploded into an atomic showdown after the Soviet Union installed nuclear missiles in Cuba, only ninety miles off American shores. It was a terrible gamble for Nikita Khrushchev, the unpredictable Soviet premier, who had the missiles sent to Cuba after asking his advisors, Why not throw a hedgehog into the United States pants?

![McDowell - God-Breathed]: the Undeniable Power and Reliability of Scripture](/uploads/posts/book/219249/thumbs/mcdowell-god-breathed-the-undeniable-power-and.jpg)