Critical Reflections on Latin America

Critical Reflections on Latin AmericaThe Second Conquest of Latin America

Coffee, Henequen, and Oil during the Export Boom, 18501930

Edited by

Steven C. Topik

and

Allen Wells

University of Texas Press, Austin

Institute of Latin American Studies

Copyright 1998 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 1998

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, Texas 78713-7819

utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library ebook ISBN: 978-0-292-75095-1

Individual ebook ISBN: 978-0-292-78566-3

DOI: 10.7560/781573

The second conquest of Latin America : coffee, henequen, and oil during the export boom, 18501930 / edited by Steven C. Topik and Allen Wells.

p. cm.(ILAS critical reflections on Latin America series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-292-78153-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Coffee industryLatin AmericaHistory. 2. Henequen industryLatin AmericaHistory. 3. Petroleum industry and tradeLatin AmericaHistory. 4. ExportsLatin AmericaHistory. I. Topik, Steven. II. Wells, Allen, 1951-. III. Series: Critical reflections on Latin America series.

HD9199.L382S4 1998

382.6098dc21 97-32607

CIP

Contents

1. Introduction: Latin Americas Response to International Markets during the Export Boom

Steven C. Topik and Allen Wells

2. Coffee

Steven C. Topik

3. Henequen

Allen Wells

4. Oil

Jonathan C. Brown and Peter S. Linder

5. An Alternative Approach

Mira Wilkins

6. Retrospect and Prospect: The Dance of the Commodities

Steven C. Topik and Allen Wells

Epilogue

Steven C. Topik and Allen Wells

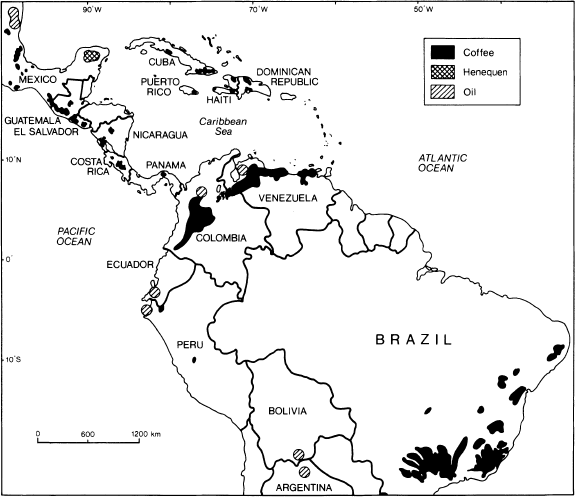

Map

Tables

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Graphs

Chapter 4

This book began as a conversation. Noting that politicians in Latin America, the United States, and much of the rest of the world have returned to their blind faith in the magic of the market, free trade, and small government, we were struck by the degree to which decision makers are suffering from historical amnesia. Because we had spent decades studying export economies in Mexico and Brazil, we knew that todays new world order was not so new. We had heard many of the arguments, the praise, and the predictions before, and we knew the dead end that export economies had proved to be historically in Latin America.

We responded as academics are wont to do: we organized a panel on the legacy of export economies at the American Historical Association in December 1992. We invited Jonathan Browna noted specialist on petroleumto discuss oil, and two distinguished commentatorsMira Wilkins, pioneering student of the history of multinational corporations and international business in general, and Carlos Marichal, an expert in international finance. The panel generated so much discussion and provoked so many new questions that we knew our work was not done. We then decided to publish a small volume to bring our questions and perspective to the scholarly and general public.

Fortunately, Theresa May, codirector of the University of Texas Press, and Virginia Hagerty of the Institute of Latin American Studies at the University of Texas-Austin, shared our vision. They gave us the space and time to develop our ideas further and we are grateful.

In the years between conversation and text, we incurred numerous intellectual debts, indeed, too many to acknowledge. Intellectual work is by definition teamwork, since we work in communities of knowledge in which our understandings, our questions, our very words are collective actions. We found working together an extremely valuable and enriching experience. Some people stand out, however.

Steven Topik would like to thank Julie Charlip, Elizabeth Dore, Lowell Gudmundson, Catherine LeGrand, Alan Knight, Colin Lewis, Hector Lindo-Fuentes, Carlos Marichal, Mario Samper, and Rosemary Thorp. He benefited from sharing his ideas on coffee at the Tercer Congreso de Historia Centroamericana, San Jos, Costa Rica, in July 1996; at the Latin American Export Economies Conference at Lake Atitln, Guatemala, in December 1996; at the Reinventing Latin American History in the Post-Cold War Conference in Riverside, California, in February 1997; and at the Market Integration Conference in Lund, Sweden, in March 1997. Travel funds from the School of Humanities of the University of California-Irvine made much of this possible.

Allen Wells expresses thanks to Norman Owen, Louis Johnson, and Kenneth Lewellen. Colleagues at the School of Social Sciences at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey, especially Albert Hirschman, were helpful in clarifying some of his thinking during his year in residence during 19951996. He presented preliminary papers at the Council of Latin American Studies Lecture Series, Peasants, Democracy and Development, Yale University, in February 1993, and the Conferencia Nacional sobre el Henequn y la Zona Henequenera in Mrida, Yucatn, in October 1992. Jeremy Adelman and Marshall Eakin carefully read the manuscript and offered thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Steven Topik dedicates this volume to Martha Jane Marcy Topik, who greeted him with a fresh cup of coffee in the early morning and patiently listened to him drone on about coffee the rest of the day. Allen Wells dedicates this work to Katherine Conant Wells, who, with seemingly endless patience, perspective, and wry humor, has understood the often tenuous relationshipsometimes dangling by a thread of henequen fiberbetween work and family.

Steven C. Topik, Irvine, California

Allen Wells, Brunswick, Maine

April 1997

Steven C. Topik

and

Allen Wells

Between 1850 and 1930, closer economic ties among Western Europe, the United States, and Latin America abruptly transformed Latin American societies. In some ways, this encounter was as dramatic as the conquistadors epic sixteenth-century first encounter with Native American civilizations.

Three hundred years after Corts and Pizarro, a different kind of battle raged over southern North America and South America. It was known by different namescivilization versus barbarism, progress versus tradition, folk versus modern culture, the transition from feudalism to capitalismbut its essence was always the same.

The agent of change during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was Latin Americas integration into the world economy through the export of raw materials. Both foreign investment and liberal ideology sustained this export-led model as Latin American governments not only sought to promote economic development during this era but also encouraged sweeping changes in state building and social engineering. It was clear to nineteenth-century intellectuals and politicians that economic prosperity would pave the road to the creation of a strong nation. The goal of the liberal export regime was to overthrow the previous statist colonial heritage and integrate the countries far-flung and heterogeneous inhabitants into a citizenry linked not by custom and religion but by the market. Throughout the New World, an emphasis on efficiency, productivity, and international competitiveness replaced protectionism and self-sufficiency as the hemispheres guiding principles.

![Topik Guide - TOPIK--The Self-Study Guide [For All Levels]](/uploads/posts/book/387869/thumbs/topik-guide-topik-the-self-study-guide-for-all.jpg)

Critical Reflections on Latin America

Critical Reflections on Latin America University of Texas Press, Austin

University of Texas Press, Austin