Copyright 2018 by Jason Sokol

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: March 2018

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sokol, Jason, author.

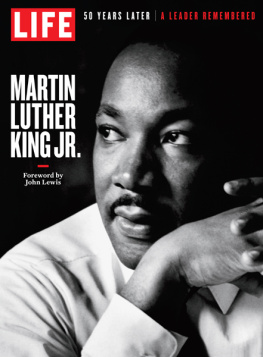

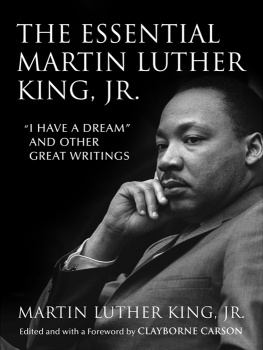

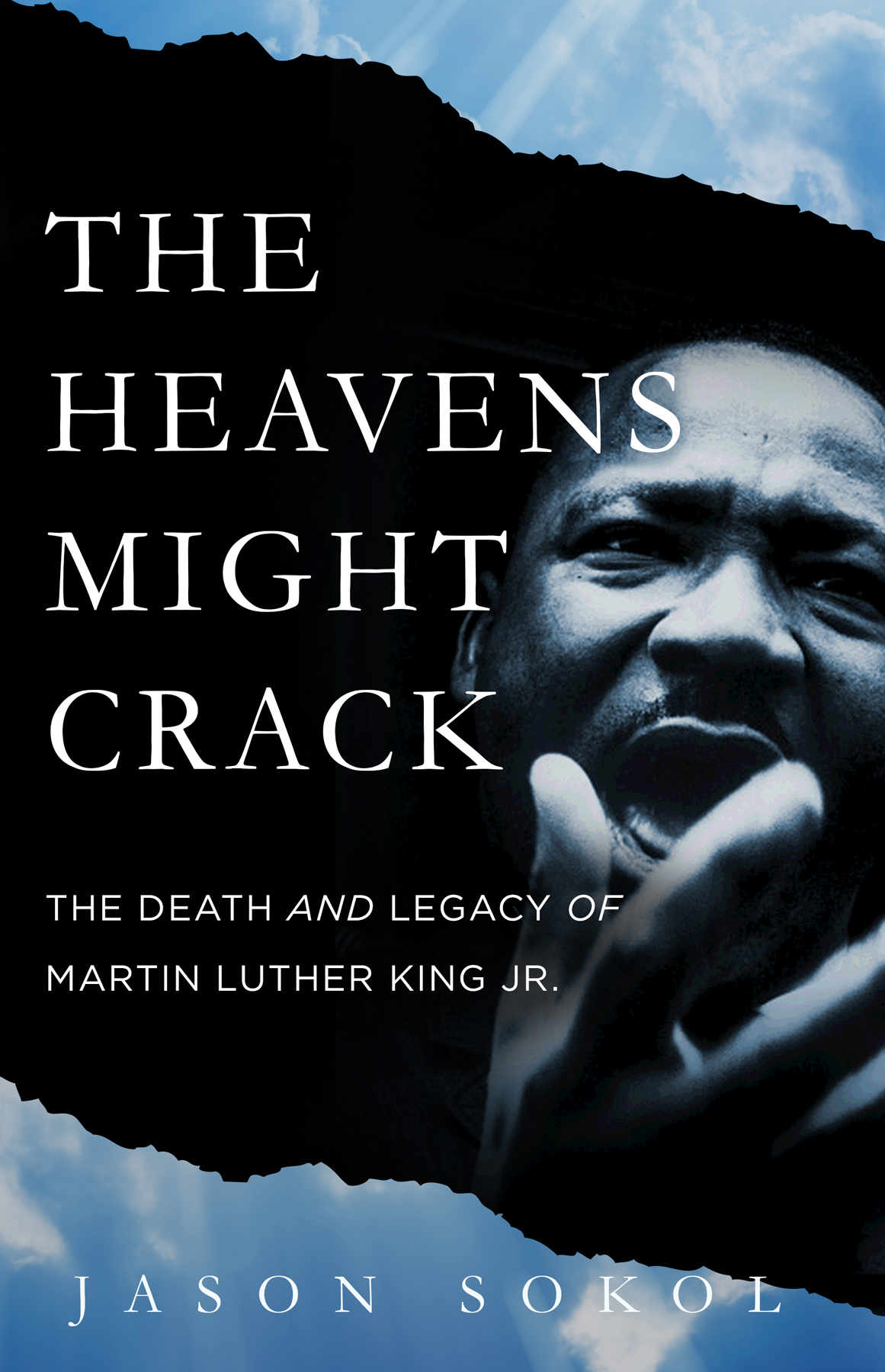

Title: The heavens might crack : the death and legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. / Jason Sokol.

Description: New York : Basic Books, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017042658| ISBN 9780465055913 (hardback) | ISBN 9781541697393 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: King, Martin Luther, Jr., 19291968AssassinationPublic opinion. | King, Martin Luther, Jr., 19291968Influence. | United StatesRace relationsHistory. | African AmericansSocial conditions. | Public opinionUnited States. | BISAC: HISTORY / Social History. | HISTORY / United States / 20th Century. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Discrimination & Race Relations. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Freedom & Security / Civil Rights.

Classification: LCC E185.97.K5 S63 2018 | DDC 323.092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017042658

ISBNs: 978-0-465-05591-3 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-9739-3 (ebook)

E3-20180222-JV-PC

Jason Sokol details with aching clarity how Kings assassination and the urban uprisings of April 1968 sent shock waves across the landscapes of Americas racial crisis and the worlds revolts. Whites, taught to fear the headline-hunting high priest of nonviolent violence, celebrated Kings death and armed themselves for race war. Militant Blacks, having warmed to Kings crusade against poverty and the Vietnam War, bitterly rejected his nonviolence. Politicians who spurned King in life immediately began to smooth an unthreatening icon for a post-racial America, a portrait at sharp odds with Kings jagged opposition to inequality and militarism. With astonishing sweep, Sokol also recovers thousands of others who redeemed the suffering by re-dedicating themselves to peace and social justice: counter-rioters who prevented even more deadly violence in Americas cities; university students who sat-in to protect the rights of maids and janitors; congressmen who pushed through landmark gun-control legislation; antiwar protesters in Berlin, Paris, and London; and Africans who proclaimed King a Son of Black Africa as they denounced American racism and South African apartheid. The heavens might have cracked, but Sokols not-too-distant mirror shimmers with intensity and the recognition of Kings continued relevance to our own travails.

Thomas Jackson, author of From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Struggle for Economic Justice

For Nina and Arlo, with love

B EFORE THE EVENING performance of April 4, 1968, conductor Robert Shaw put down his baton and stood to address the Atlanta Symphony audience. He announced that Martin Luther King Jr. had been killed. The concertgoers gasped and moaned. A Roman Catholic priest prayed for King and exclaimed, The king is dead! Long live the king!

On the opposite side of the country, author James Baldwin sat by a Palm Springs swimming pool with the actor Billy Dee Williams. The phone rang, and a friend told Baldwin of the tragedy in Memphis. It took awhile before the sound of his voiceI dont mean the sound of his voice, something in his voicegot through to me. At first, Baldwin felt numb. Then an unbelieving wonder overtook him. He wept briefly, and finally succumbed to a shocked and helpless rage. For years, that evening would remain a blur in Baldwins memory. Its retired into some deep cavern in my mind.

In Blacksburg, Virginia, hundreds of college students had packed an auditorium to watch Senator Strom Thurmond, the longtime segregationist from South Carolina, debate the liberal satirist Harry Golden. A Virginia Tech dean interrupted the debate to inform the audience that King had been assassinated. Though the student body was almost all white, no Negro audience could have been more shocked by the news, Golden recounted. I heard groans of despair. The dean asked

The fatal shot rang out in Memphis, and it quickly rippled across the nation and the world. News of Kings murder stopped people in their tracks and rendered them speechless, moved many to tears and others to celebration, drove some to violence and still others to political activism.

African Americans were overcome with grief and gripped by rage. Despair seized Dorothy Newby, an eighteen-year-old who attended Hamilton High School in Memphis. I wanted the world to end completely I felt there was no reason to continue living, and above all I wanted to kill myself. If such a foul deed could occur in this world, she wanted to opt out of it. Her classmate, seventeen-year-old Frankie Gross, broke down in tears. Gross knew that people all over the world mourned his death, and I felt better knowing it. At the same time, he realized that a violent anger was surging through the black neighborhoods of Memphis. You could see and feel the hate in the Negro community after the assassination. People took guns to work the next day just waiting for any white person to do anything wrong. The actions of law enforcement officials only intensified their fury. The National Guard rolled through the city in tanks and attempted to seal off African American neighborhoods. Black Memphians felt doubly victimized. Their leader was slaughtered by a white assailant and then they were treated as criminals.

Clarence Coe, an African American who worked at Memphiss Firestone factory, believed the race war had finally arrived. On Thursday evening, April 4, Coes foreman advised him that the plant was closing

Martin Luther King was in Memphis to stand with striking sanitation workers, 1,300 black men whose struggle for dignity dovetailed with Kings own Poor Peoples Campaign. King spent the final months of his life waging that fight against economic inequality. He envisioned masses of the nations poor, black and white and Latino, converging on the Washington Mall in a show of nonviolent civil disobedience. After Kings death, many African Americans in Memphis felt an unspeakable sense of loss. They were ashamed by the thought that their own community had failed to shelter him. They were also enragedangry with Mayor Henry Loeb for bitterly opposing the sanitation strike, and infuriated at Memphiss white citizens for denigrating King and denouncing the strikers. They were incensed that FBI officials could seemingly spy on King at all hours, yet fail to protect him from an assassins bullet and then allow the shooter to flee the city. Like African Americans across the country, they were outraged at the many whites who had given encouragementtacit as well as explicitto all of the King-haters and created a favorable climate for the assassin.