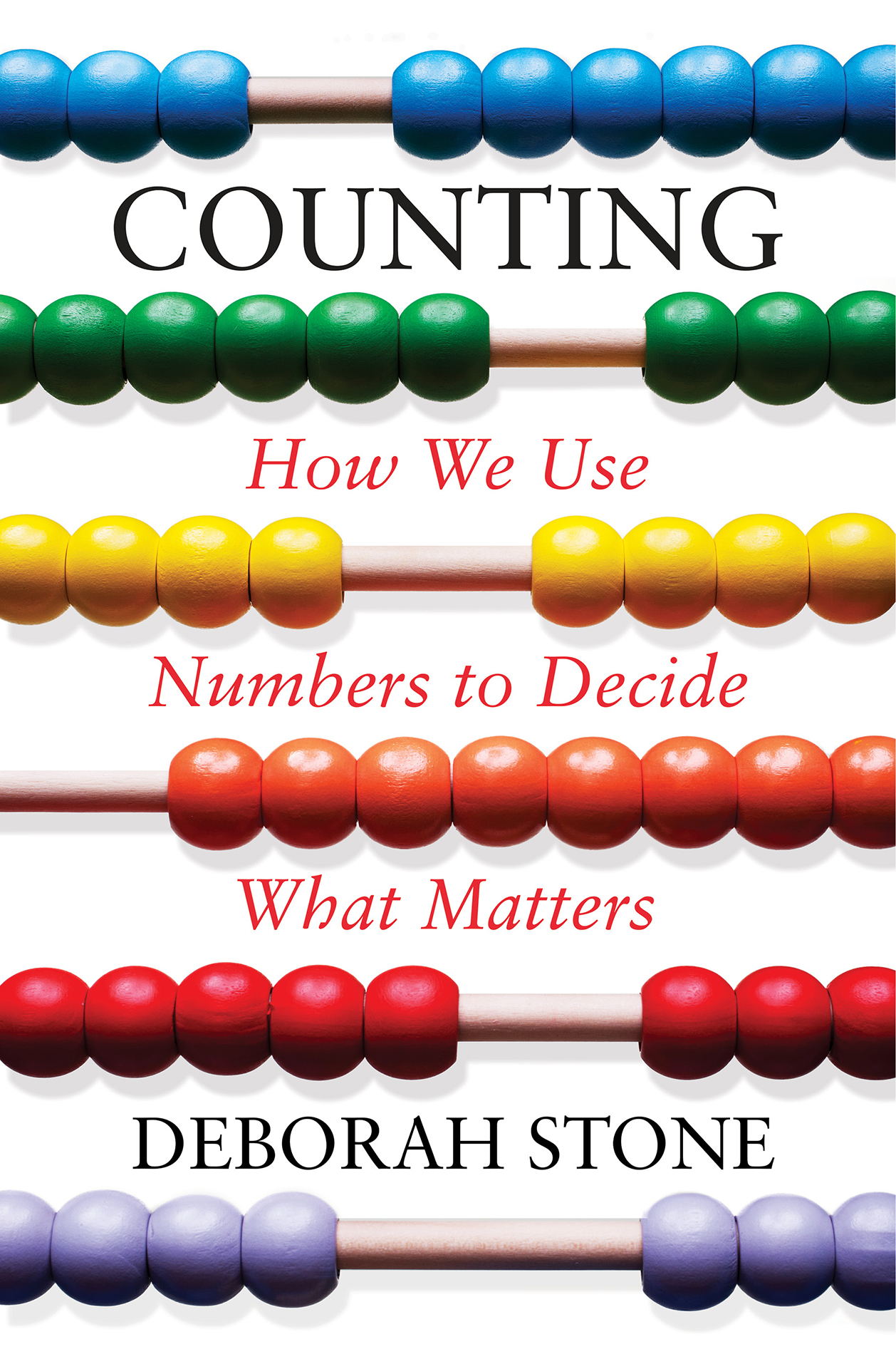

Deborah Stone - Counting

Here you can read online Deborah Stone - Counting full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Liveright, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Counting

- Author:

- Publisher:Liveright

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Counting: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Counting" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Counting — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Counting" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Counting

How We Use Numbers to

Decide What Matters

DEBORAH STONE

Liveright Publishing Corporation

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

COUNTING

D uring my sophomore year of college, I had an identity crisis.

I loved math and science courses because they reassured me there is some order in the world. Besides, math and science problems had right answers and I was good at finding them. But when daytime coursework passed into late-night dorm sessions, literature, philosophy, and politics posed more urgent and discussable questions: What is the meaning of life, and how can people live together to make the best of it? These questions had no right answers and my grades told me I wasnt very good at dealing with ambiguity. But at age 18, those were the questions I desperately needed to pursue.

I was trapped between the two cultures, Sir Charles Snows phrase for the chasm he observed between scientists and literary types. The two camps simply couldnt talk to each other. They spoke different languages, they thought differently, and they certainly had different ways of pursuing truth. My father had given me Snows book in high school. At the time, it didnt speak to me. Now I saw that Dad had sensed my struggle long before I did.

Browsing one day in a campus bookstore, I found a ray of hope in an essay called The Creative Mind by Jacob Bronowski. Bronowski challenged the two-cultures divide by showing that creativity is the same process for scientists, poets, and painters. They all grope for new understanding by finding hidden likenesses that others havent noticed. Scientists, he wrote, dont make discoveries by taking enough readings and then squaring and cubing everything in sight. Copernicus couldnt have gotten the idea that the earth revolves around the sun with only a camera and a measuring stick. His first step was a leap of imaginationto lift himself from the earth, and put himself wildly, speculatively into the sun. From that vantage point, he saw that the orbits of the planets would look simpler if they were looked at from the sun and not the earth. For Bronowski, Copernicuss creative moment, the poets metaphor, and the painters imagery are all of a kind.

I felt liberated by Bronowskis insight. I didnt know how I was going to reconcile the two cultures for myself, but I knew it would require some leaps of imagination. I bolted from my science path and through a circuitous route became a political scientist, despite an ominous note from a professor on one of my papers: BThis is a credible effort, but youll never be a political scientist. Political science is an oxymoron if ever there was one. The very name spans the two cultures. I should have known I would remain caught between the two cultures for the rest of my days.

I landed my first teaching job in another oxymoron, a new program called Policy Science. My colleagues were positively smitten with numbers. There was no policy problem and no personal problem (Should I marry my girlfriend or boyfriend?) for which statistics couldnt find the best answer. Almost everyone else on the faculty was teaching our students how to find the mathematically best answer to policy problems. As the only political scientist, my job was to teach them how to get their neat solutions through the messy political process. I didnt know much about statistics but I sure knew they dont carry much weight with politicians. I knew that stories are more persuasive than numbers. And I knew that politicians, advocates, and activists could use numbers for both good and evil.

On the side of good, there was asbestos. In the 1960s, labor unions and doctors used numbers to document that breathing asbestos fibers causes mesothelioma, a fatal lung cancer. Finding the link between asbestos and cancer was one of many public health triumphs indebted to numbers. On the side of evil, there was the Vietnam War. Robert McNamara, Lyndon Johnsons defense secretary, measured success in Vietnam by counting dead Vietnamese people, the infamous body counts of the nightly news. Over the course of my career, Ive seen numbers be touted as either Jekyll or Hyde. At one moment, numbers are the only facts we can trust. At another, there are lies, damned lies, and statistics.

Nowadays, the battle between the two cultures often takes place under the banner of Numbers Versus Stories. My town, Brookline, Massachusetts, hosts the first marijuana dispensary in the Greater Boston area. As the town was getting ready to license a second one, nine hundred residents signed a petition asking the town to put restrictions on both dispensaries. At a public hearing, neighbors complained of litter, public urination, and consuming in public. They spoke about crowded sidewalks, traffic congestion, and parking problems, all harmful to nearby businesses. One woman said she felt afraid to walk home at night.

Stories arent facts, the president of the first company responded. We take the concerns of our neighbors very, very seriously and will continue to do so, but facts and data really need to drive this discussion. By facts and data, she meant numbers. She was staking a familiar claim: People are hopelessly subjective and biased. They see the world from their own narrow point of view. Their anecdotes are nothing but fleeting glimpses of their distorted perspective. Numbers, by contrast, are objective.

Im all in favor of the pot shops. The stories arent facts gambit bothers me, though, because it dismisses citizens who cant express their experience in numbers. Calling for more data makes a great stalling tactic, too. It tells town officials, Stick with the status quo until we get some numbers.

On the other hand, whats not to love about objectivity? Objective means fair and impartialthe opposite of biased and playing favorites. For scientists, objectivity means that when different people study the same problem or count the same things, theyll get the same answer. Theyll get the same answer because, if theyre good scientists, they strip themselves of personal biases. In the words of someone who bills himself as a science advocate, There is a world. It is real. It is home to objects and processes that exist independent of us and our beliefs. I love that world. Its the world where I can spend hours at a pond contemplating the beavers and frogs, the wind gusts and water ripples, the trees, the clouds, and an oncoming storm. None of those objects and processes gives two hoots about what I think of them. That world is a physical world. It is home to things like rocks and tornadoes that dont morph according to how we feel about them.

This book is not about that world. This book is about the social world. The social world is filled with human ideas and experiences that most definitely shapeshift in response to our thoughts and feelings. This book is about how we take the measure of those nebulous notions connected to the meaning of life that goaded me in college and still do. How do we count how much freedom and equality we have? How do we decide who is poor or disabled and deserves societys help? How do we measure democracies to know how democratic they are and how we can make them more so? How do we measure pain so doctors can help us cope with it? How do we measure students knowledge and teachers teaching ability to find out how the two are connected? How do we count racial and ethnic identity, and why

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Counting»

Look at similar books to Counting. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Counting and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.