About Island Press

Since 1984, the nonprofit organization Island Press has been stimulating, shaping, and communicating ideas that are essential for solving environmental problems worldwide. With more than 1,000 titles in print and some 30 new releases each year, we are the nations leading publisher on environmental issues. We identify innovative thinkers and emerging trends in the environmental field. We work with world-renowned experts and authors to develop cross-disciplinary solutions to environmental challenges.

Island Press designs and executes educational campaigns in conjunction with our authors to communicate their critical messages in print, in person, and online using the latest technologies, innovative programs, and the media. Our goal is to reach targeted audiencesscientists, policymakers, environmental advocates, urban planners, the media, and concerned citizenswith information that can be used to create the framework for long-term ecological health and human well-being.

Island Press gratefully acknowledges major support of our work by The Agua Fund, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Bobolink Foundation, The Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation, Forrest C. and Frances H. Lattner Foundation, The JPB Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, The Oram Foundation, Inc., The Overbrook Foundation, The S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, The Summit Charitable Foundation, Inc., and many other generous supporters.

The opinions expressed in this bookare those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of our supporters.

Island Press mission is to provide the best ideas and information to those seeking to understand and protect the environment and create solutions to its complex problems. Join our newsletter to get the latest news on authors, events, and free book giveaways. Click here to join now!

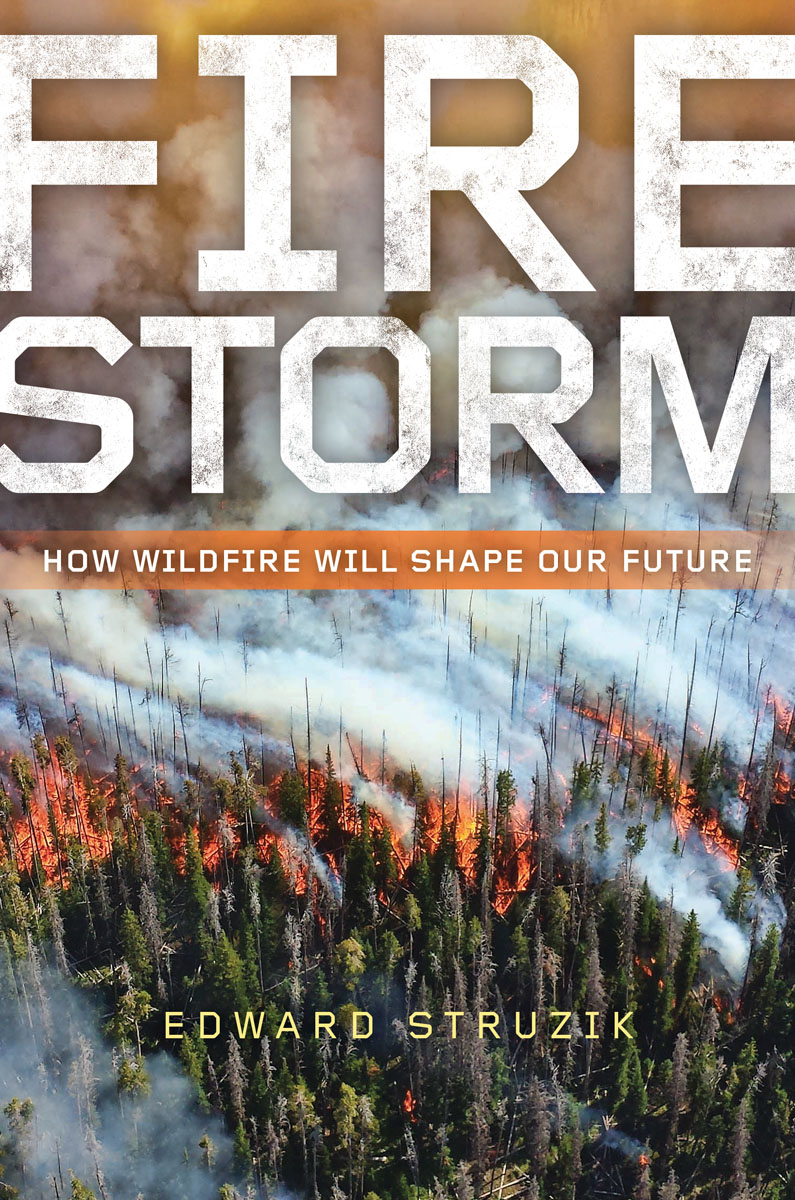

Copyright 2017 Edward Struzik

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M Street, NW, Suite 650, Washington, DC 20036

Island Press is a trademark of The Center for Resource Economics.

Keywords: Alaska, Alberta, Arctic, arsenic, asbestos, Banff, biodiversity, boreal forest, British Columbia, California, Canada, carbon bomb, climate change, Colorado, Denver, drought, fire ecology, fire management, fire suppression, FireSmart, First Nations, Fort McMurray, Horse River Fire, hydrology, Montana, mountain pine beetle, oil sands, Ontario, permafrost, resilience, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Slave Lake, spruce budworm, water quality, watershed, Wood Buffalo

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017940667

All Island Press books are printed on environmentally responsible materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my wife, Julia; my children, Jacob and Sigrid;

and to firefighters and first responders everywhere.

And to the First Nations people of Canada and the

North American native people of the United States, with

apologies for our failure to view wildfire the way you once did.

Contents

Introduction

I found myself within a forest dark, for the straightforward pathway had been lost. Ah me! How hard a thing it is to say, what was this forest savage, rough, and stern, which in the very thought renews the fear. So bitter is it, death is little more

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy

O n May 3, 2016, a rapidly spreading wildfire around Albertas oil sands capital in Fort McMurray sent 88,000 people fleeing their homes, offices, hospitals, schools, and seniors residences. The people left so quickly that they were gone before the government declared a provincial state of emergency. Thick smoke turned day into night. Embers rained down on cars and trucks as people headed south to the city of Edmonton or north to the safety of oil sands camps and First Nations communities.

By the time rains and cooler temperatures helped firefighters contain MWF-009, as the ninth regional blaze of the season is officially called, 2,800 homes and buildings were destroyed. Nearly 1.4 million acres (566,168 hectares) burned. Insurance losses were expected to amount to $3.77 billion. The total cost of the fire, including financial, physical, and social factors, is likely to be $8.86 billion. Firefighters referred to the enormous conflagration as the Horse River fire or The Beast. The second was an apt name, as the fire ended up being the costliest natural disaster in Canadian history and one of the most destructive North American wildfires in modern times. Police and firefighters fully expected to find hundreds if not thousands of bodies in burnt-out cars, trucks, and homes. It was a miracle that, except for two young people who were fatally injured in a car crash on the drive south, no one died.

That so few people perished is exceptional, especially given how much went wrong with the management of the fire and the painfully slow decision making that went into the evacuation process. There was no shortage of heroics. But egos got in the way. A unified command that would have been able to reconcile inherently different approaches by wildland and structural firefighters took too long to come together. A provincial state of emergency, which would have given the government of Alberta clear, concise, and far-reaching authority to deal with the fire, wasnt called until two days after most everyone was gone. Unhappy with how the fires were being managed, oil sands companies hired their own independent experts to evaluate the magnitude of the risks to their operations.

Megafire, a relatively new word used to describe wildfire, is by one definition a fire that burns at least 100,000 acres (40,468 hectares). These fires routinely occur in Alaska, the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and throughout the forests of western Canada, northern Ontario, most of Quebec, and the northern United States. On occasion, they burn in the soggier East Coast and Pacific Northwest regions. The Carlton Complex fire burned more than 250,000 acres on the eastern slopes of the Cascade Range in Washington in 2015. There is a reason for such fires: coniferous trees that grow in the montane, subalpine, Columbian, and boreal forests are ecologically programmed to burn.

The Horse River fire was not an anomaly as some people have suggested. Fires in Alberta have burned bigger (Chinchaga 1950), hotter (Chisholm 2001), and faster (Vega 1968). The difference between what is happening now and what was happening in the 1980s and earlier is that megafires are occurring more often, displacing more and more people, and reshaping forest and tundra ecosystems in ways that scientists dont fully understand.

What made the Horse River fire unique is that it created its own

When the Horse River fire was finally under control on the fifth day of July, I was in a burned-out area in the boreal forest just north of Fort McMurray, catching nighthawks with Elly Knight, a graduate student from the University of Alberta in Canada. The Common Nighthawk is a small bird that is not a hawk, nor is it strictly nocturnal. Because its population has plummeted in North America, it is also no longer common. Nonetheless, it thrives in postfire landscapes, as Knight had discovered in the weeks before I arrived on the scene.

Next page