Praise for

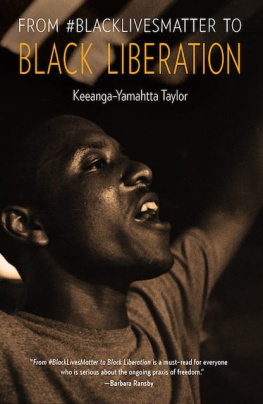

From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylors searching examination of the social, political, and economic dimensions of the prevailing racial order offers important context for understanding the necessity of the emerging movement for black liberation.

Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow

Class matters! In this clear-eyed, historically informed account of the latest wave of resistance to state violence, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor not only exposes the canard of colorblindness but reveals how structural racism and class oppression are joined at the hip. If todays rebels ever expect to end inequality and racialized state violence, she warns, then capitalism must also end. And that requires forging new solidarities, envisioning a new social and economic order, and pushing a struggle to protect Black lives to its logical conclusion: a revolution capable of transforming the entire nation.

Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination

With political eloquence, intellectual rigor, and an unapologetically left analysis, the brilliant scholar-activist Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has provided a powerful contribution to our collective understanding of the current stage of the Black freedom struggle in the United States, how we arrived at this point, and what battles we need to fight in order to truly achieve liberation. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation is a must read for everyone who is serious about the ongoing praxis of freedom.

Barbara Ransby, author of Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has a strong voice, a sharp mind, and a clear, readable style that all come together in this penetrating, vital analysis of race and class at this critical moment in Americas racial history.

Gary Younge, editor at large, Guardian

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor brings the long history of Black radical theorizing and scholarship into the neoliberal twenty-first century with From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation . Her strong voice is deeply needed at a time when young activists are once again reforging a Black liberation movement that is under constant attack. Deeply rooted in Black radical, feminist, and socialist traditions, Taylors book is an outstanding example of the type of analysis that is needed to build movements for freedom and self-determination in a far more complicated terrain than that confronted by the activists of the twentieth century. Her book is required reading for anyone interested in justice, equality, and freedom.

Michael C. Dawson, author of Blacks in and out of the Left

From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation is a profoundly insightful book from one of the brightest new lights in African American Studies. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor invites us to rethink the postwar history of the United States and to place the actions of everyday people, including the hundreds of thousands of African Americans who participated in the urban rebellions and wildcat strikes of 1960s and 1970s, at the forefront of American politics. By doing so, she offers up a usable past for interpreting the current anti-state-sanctioned-violence movement sweeping the United States in the early twenty-first century. This timely volume provides much needed analysis not only of race and criminalization in modern American history but of the specific roles played by a bipartisan electoral elite, the corporate sector, and the new black political class in producing our current onslaught of police killings and mass incarceration in the years since the Voting Rights Acts passage. Taylors fluent voice as historian and political theorist renders legible the accomplishments and, perhaps most importantly, the expansive possibilities of a new generation of black youth activism.

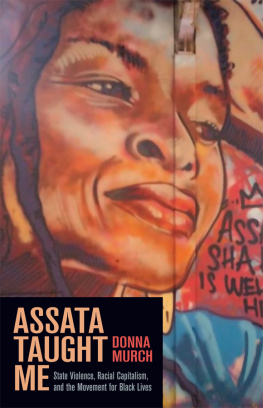

Donna Murch, author of Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has given us an important book, one that might help us to understand the roots of the contemporary policing crisis and build popular opposition capable of transforming the current, dismal state of affairs. Equal parts historical analysis and forceful polemic, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation provides a much-needed antidote to the postracial patter that has defined the Obama years, but it also serves as a proper corrective for the new civil rights movement posturing of some activists. Against such nostalgic thinking, Taylor reminds us of the new historical conditions we face and the unique challenges created by decades of African American political integration. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation sketches a politics that rightly connects antipolice brutality protests and a broader anti-capitalist project. Everyone who has grown sick of too many undeserved deaths at the hands of police and vigilantes should read and debate this book.

Cedric G. Johnson, author of Revolutionaries to Race Leaders: Black Power and the Making of African American Politics

Chapter Two

From Civil Rights to Colorblind

If the problem of the twentieth century was, in W. E. B. Du Boiss famous words, the problem of the color line, then the problem of the twenty-first century is the problem of colorblindness, the refusal to acknowledge the causes and consequences of enduring racial stratification.

Naomi Murakawa , The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America

I n his book Black Reconstruction in America , W. E. B. Du Bois described the promise of Reconstruction as a brief moment in the sun for Blacks, before its disastrous end moved African Americans back again toward slavery. The receding of the Black Power insurgency during the 1970s didnt return Blacks to a state of neo-slavery, but the hope and expectations raised by the movement of the 1960s proved elusive.

By the end of the 1970s, there was little talk about institutional racism or the systemic roots of Black oppression. There was even less talk about the kind of movement necessary to challenge it. Instead, when Ronald Reagan ran for the Republican presidential nomination in 1976, he made a play for the racist vote by complaining about a fictitious strapping young buck using food stamps to buy T-bone steak. He famously invented the stereotypical welfare queen, who, he said, used 80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans benefits for four nonexistent deceased veteran husbands, as well as welfare. Her tax-free cash income alone has been running $150,000 a year. These were familiar racist baits for the white conservative electorate: lazy Black welfare cheats getting something for nothing. But in the aftermath of the Black revolution of the 1960s, politicians no longer felt comfortable displaying their racist credentials upon their sleeves. The strapping buck and the welfare queen were assumed to be Blackbut, politically, Reagan and others could not risk saying so. Even with its coded language, Reagans conservatism was at this point considered on the extreme right of mainstream politicsit would take the rest of the decade to become dominant. The Black movement of the 1960s had disgraced outward displays of racial animus, even as race continued to animate American politics by other means. Ultimately, Reagan lost the nomination to Gerald Ford by a narrow margin, but the trajectory of mainstream politics was clear. It was not just the right: the Democratic Party was also moving quickly to abandon its very recent association with the civil rights movement. On a campaign-trail stop in Indiana, Jimmy Carter, who was campaigning for the 1976 Democratic nomination, remarked:

I have nothing against a community thats made up of people who are Polish, Czechoslovakian, French Canadians or blacks who are trying to maintain the ethnic purity of their neighborhoods.... But I dont think the government ought to deliberately break down an ethnically oriented community deliberately by injecting into it a member of another race.... Im not trying to say that I want to maintain with any kind of government interference the ethnic purity of neighborhoods. What I say is the government ought not to take as a major purpose the intrusion of alien groups into a neighborhood, simply to establish that intrusion.

Next page