This book is dedicated to the memory of Rose Gregoire, Apinam Pone and Gail Valaskakis, individuals who dedicated their lives to finding solutions.

Introduction

In September 1981, Peter Penashue and Edward Nuna, two Innu teenagers from Sheshatshiu, Labrador, came to live in my three-storey, century-old house in St. Johns. They were the only two students in their year to have reached grade eleven, and theyd come to St. Johns to finish high school. In the ten months that followed, the three of us became friends, sharing confidences and weathering lifes ups and downs. Peter and Edward trusted me to guide them through the daunting and unfamiliar territory of the city. In return, my life was enriched by their humour, their courage and the insights I gained into their ancient culture, shaped thousands of years ago by the northern Quebec and Labrador landscape. Innu history retains a memory of the Ice Age, and Peter and Edwards favourite story was about Tshakapesh, an Innu hunter who killed a mammoth to feed his people.

From Peter and Edward I learned too about the extent of alcoholism in Sheshatshiu. Edward was respectful of his parents, but their use of alcohol had prevented them from properly looking after their nine children, forcing him many times to go from house to house for food. Peters family also struggled with alcoholism, but he exhibited greater self-confidence; his resilience came from his time in nutshimit (the country), where his family lived while his father and grandfather hunted. Sheshatshiu had not existed until the early 1960s; until then, most Innu still lived in tents and provided their own food by travelling over their land in canoes and toboggans. The move changed Peters father, as it did so many others; in the new village, the able hunter became a drunk.

This was a riddle for me. How could a change in lifestyle produce such self-destructive behaviour from such fine people? I was invited to spend time with Peter and Edwards families, who treated me with great hospitality and kindness. From them I learned more about the dichotomy between life on the land and life in the village. Many households in Sheshatshiu were headed by alcoholics who were transformed on the land into hunting camp leaders, because they were such great providers of warmth and food. I became especially close to Peters mother, Tshaukuesh (Elizabeth Penashue).

I moved to Montreal, where other interests preoccupied me. In 1987, while watching the news one evening, I was shocked to see a report from Labrador that showed Tshaukuesh and others being led away by police for hunting caribou illegally. Their actions were part of an organized protest by the Innu against provincial wildlife regulations that restricted the Innu to Sheshatshiu for most of the yearas if we were in prison, Tshaukuesh later told me. Innu activism heated up even more when Canada announced its intention to build a NATO jet bomber training centre in Goose Bay. The people of Sheshatshiu had never signed a treaty or a land claims agreement with Canada, and they feared that the frequent flights by jet bombers practising low-level flying and air-to-air combat training would do irreversible damage to caribou and other animals.

It was inspiring to see the Innu community come together with such passion to protect the environment. But their activism took great emotional energy, and by the late 1980s, the people of Sheshatshiu were bitter and exhausted by the political struggle. The younger generation had lost confidence in the traditional way of life but were left with little of spiritual or material value to replace it. A decade after the protests organized by their parents, young children in Sheshatshiu and Davis Inlet began routinely inhaling gasoline to get high. In many First Nations communities across the country, similar social problems had been evident for some time, often arising after people were forced off their traditional lands.

The catalyst for this book was an op-ed piece by John Gray that appeared in the Globe and Mail on March 8, 2005. Gray described the problems that the Innu people in the Labrador community, Davis Inlet, were having adjusting to their relocation to Natuashish, a community that had been built from scratch. There had been reports of more suicides and more solvent-abusing children, of financial corruption. It was Grays last paragraph that goaded me into action. He wrote of his fear that these problems might have no solutions, that the lives of the Innu might never be better. The disaster of Davis Inlet and Natuashishand there are other Aboriginal communities across the country similarly afflicted he wrote, is that nobody knows what to do.

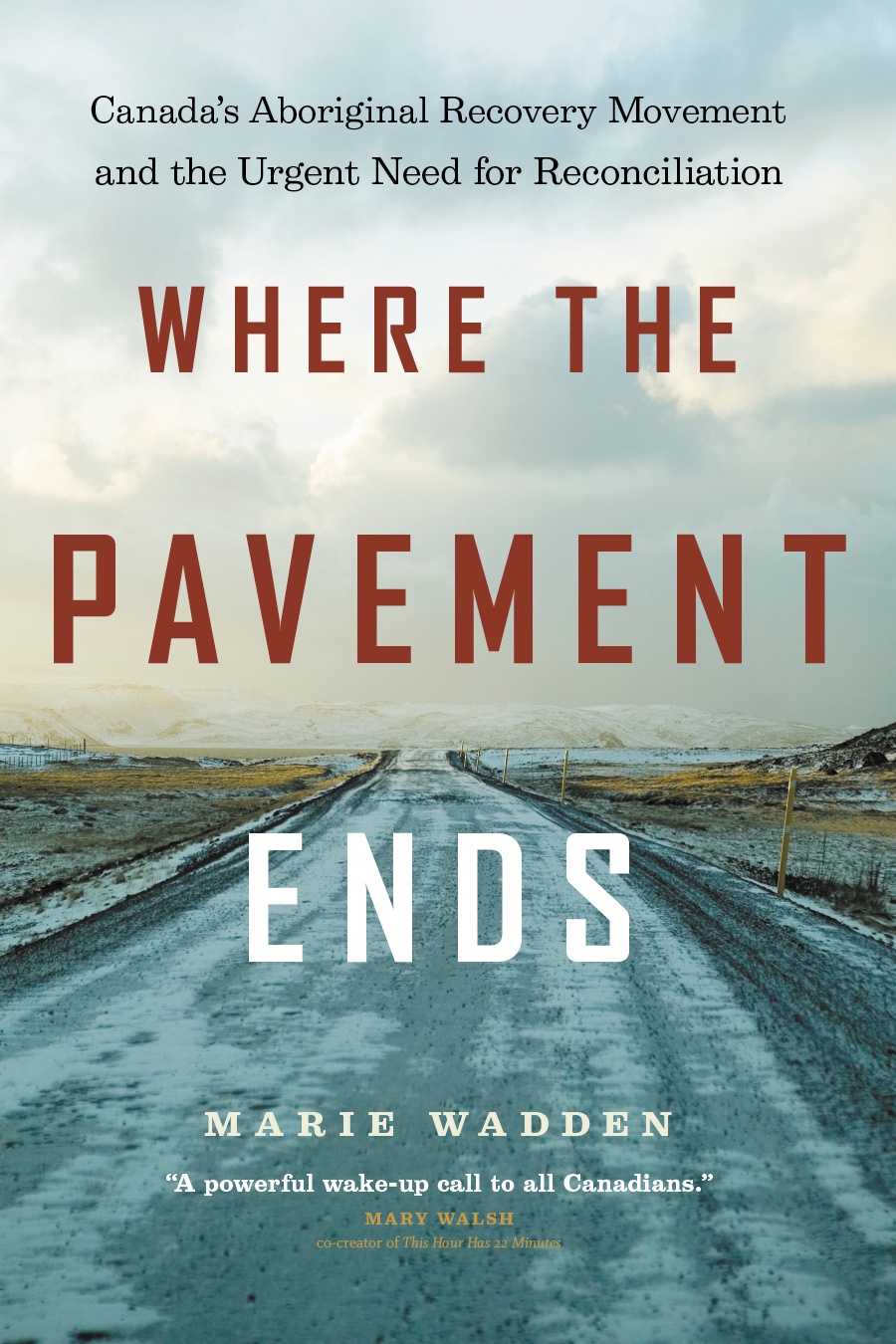

In 2006, with the generous support of the Atkinson Charitable Foundation, I set out to look for people who do know what to do. My research, published as a series of stories in the Toronto Star , took me across the country, to Inuit communities in the Arctic and to First Nation and Metis communities from Labrador to British Columbia. Few of the communities I visited were marked on road maps or signposted on provincial highways. Often, I knew Id come to the reserve because I had reached the end of the pavement.

At the outset of my journey, I was unaware of the incredible work Aboriginal people are doing in the area of addiction. A vibrant Aboriginal healing movement has sprung up, with recovery programs being created in many communities. Yet, despite their many successes, these programs are seriously underfunded and understaffed, placing their continued existence in jeopardy.

The situation could not be more urgent. After visiting Aboriginal communities, talking to numerous Aboriginal activists and reading dozens of books and countless reports, I have come to believe that the very survival of the first peoples of this country is at risk. Inuit women have raised the alarm about the high rates of violence in their communities. Experts on fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) warn of an impending social disaster if rates of alcohol abuse are not curtailed in Aboriginal communities. Sober people on reserves are begging for mental health and addiction training, and for income parity for the professionals who work in their communities. First Nations and Inuit leaders are calling for relief from a severe housing shortage and a national health budget that reflects the needs of the Aboriginal population. For Aboriginal people to take responsibility for their own lives, they need the political, moral support and financial support of the Canadian population. Figures released by Statistics Canada in January 2008 indicate just how critical the situation is. Over the past decade, the Aboriginal population in Canada has grown by 45 per cent; the average age of an Aboriginal person is twenty-seven, compared to an average of forty for non-Aboriginal Canadians. This is our countrys most dynamic demographic, but our policies are not keeping pace with the challenges.

Much of the debate about solving Aboriginal problems revolves around public spending. Some non-Aboriginals are critical when they hear that $8 billion a year in federal money is spent on Canadas 1.5 million Aboriginal people. Wheres all our money going? they ask. Aboriginal people have another way of looking at the issue of our money. They believe that it is being made off their land. Very little of that money comes back to them in effective ways, and what is provided is often first siphoned by the bureaucratic agencies that dispense it.

The pages of this book contain some answers. None of them are simple, since the problems are complex. Taken together, though, they outline some necessary steps on the path to finding solutions. Through Canadas Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was launched in 2008, we have an opportunity to create a groundswell of support. The next five years will be crucial for raising public awareness about the damage done to Aboriginal society by the most egregious of Canadian government policies, the 1920 legislation that required First Nations parents to surrender their children to residential schools. We must make social healing in Aboriginal communities an immediate national priority. We must also demand public policy that guarantees First Nations, Inuit and Metis people the right to live as full and equal citizens. In these ways, we can offer true support to those committed to restoring health and happiness for the next generation.