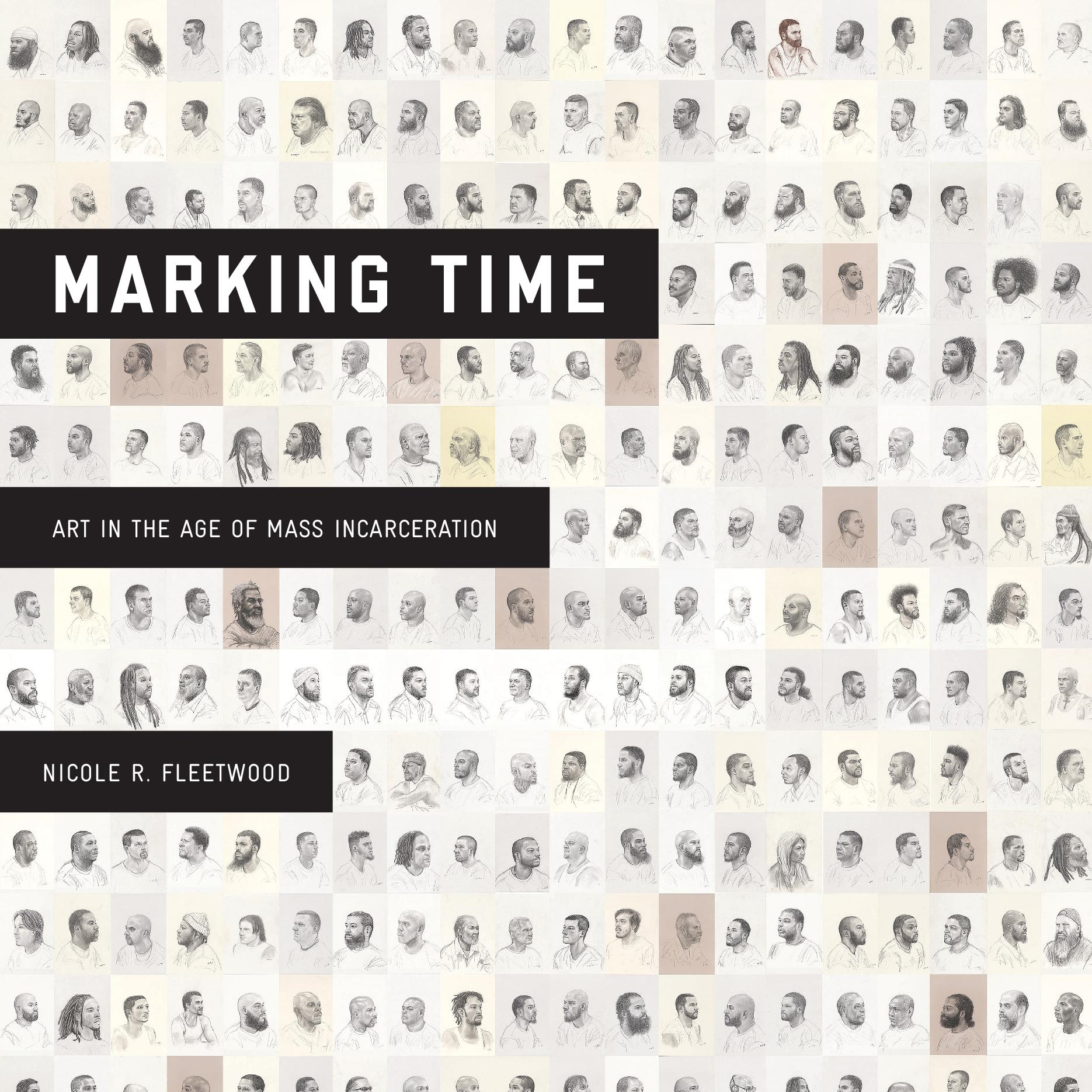

Nicole R. Fleetwood - Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration

Here you can read online Nicole R. Fleetwood - Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

MARKING TIME

ART IN THE AGE OF MASS INCARCERATION

NICOLE R. FLEETWOOD

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTSLONDON, ENGLAND2020

Copyright 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Publication of this book has been supported through the generous provisions of the Maurice and Lula Bradley Smith Memorial Fund.

Jacket art: Detail from Pyrrhic Defeat by Mark Loughney

Jacket design: Sam Potts

978-0-674-25090-1 (EPUB)

978-0-674-25091-8 (MOBI)

978-0-674-25092-5 (PDF)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from loc.gov

ISBN: 978-0-674-91922-8 (cloth)

For Allen, DeAndre, and Eric.

For all my relations.

Incarceration has reshaped my family and my hometown in southwest Ohio. Countless relatives have been arrested and detained; some have been convicted and sentenced, while others have been held indefinitely and then let go. One cousin was held in a county jail for several months without any charges ever being filed. Some of us have been profiled by police and falsely accused of crimes. Others have been convicted of serious crimes and sentenced to long periods in prison. The same month that I graduated from college, two of my closest cousins were convicted and sentenced for involvement in the death of another young man from our community. There has never been a time in my life when prison didnt hover as a real and present threat over us. As a young child, I recall Sunday visits with my mom to see my uncle, who was locked away in a prison thirty minutes from our hometown. Looking through files after my grandmother passed, I was struck by how many times she had leveraged the modest home she owned in order to bail out a relative.

We lived in a mill town that had experienced the woes of factories closing. The unionized manufacturing positions that had sustained our working-class and lower-middle-class black community for a couple of generations were no longer available. Studies of mass incarceration and the carceral state offer insightful explanations and historical accounts of what many of us witnessed and experienced in our communities: the mass removal of family members, neighbors, and friends, along with the permanent stigma on the imprisoned and their families.

As I came of age in the 1980s and early 1990s, people around me, mainly young black men but also older women and men, were being shipped off to prison at such a frequency that their sudden disappearance and long-term absence became the norm. Boys my age who went to elementary and junior high school with my cousins and me were there and then gone, some never to return. They were invisible to us and hard to reach because of all the mechanisms that the carceral state uses to separate the imprisoned from their families and communities. We had no words to describe the utter devastation, the despair.

As prisons rendered more and more people invisible, a spectacular visual assault on residents in communities like mine helped to justify mass incarceration. Representation was an essential tool to support tough crime policies and punitive sentencing. Assaultive and dehumanizing images, such as wanted posters, arrest photographs, crime-scene images, and mug shots circulated frequently in local and national media and reinforced the practices of aggressive policing and dominant notions of black criminality. Stories of the rampant devastation of the crack era that portrayed young street dealers as monsters circulated. Opening our local newspaper was often cause for pain and embarrassment, as photographs of people we knew in handcuffs were all too common; often these were images of black children and teenagers, infamously referred to as superpredators in the 1990s by journalists and politicians, most notably Hilary Clinton. One of the most well-known and egregious examples was the use of visual media to portray the so-called Central Park Five, now known as the Exonerated Fivefive black and Latino teenage boys who were falsely accused and convicted of raping a white womanas a wolf pack. Such representations sparked fear and animus in the mainstream American public, especially among people distant from the communities living under the terror of aggressive policing and imprisonment, but also among some people who lived in those neighborhoods.

At the same time, there were other images being produced about mass incarcerationimages that rarely made the news and had little or no public circulation. They offered different narratives of prisons and their impact. These were not journalistic, scholarly, or legal documents. They were a diverse assortment of artworks and illustrations coming from prison: studio photos, handmade greeting cards, drawings, and other pieces of art made by incarcerated people. Incarcerated relatives sent home graphite drawings and birthday cards designed by artists in prison. In some prisons, we could take photographs together when we visited our relatives and friends. The visiting rooms where we sat with our imprisoned relatives and friends often displayed paintings, miniatures, and sculptures made by incarcerated people. These objects were not new forms of prison art, but as the size of the prison population boomed, the visual culture of mass incarceration grew along with it.

I started working on this book as a way to deal with the grief about so many of my relatives, neighbors, and childhood friends who were spending years, decades, or life sentences in prison. It was also an effort to connect with others who are separated from their loved ones by prisons, parole, policed streets, and other forms of institutional and quotidian violence. I began by displaying photos of incarcerated relatives around my apartment, partly as an attempt to work through my own discomfort with the pictures of them in prison and to bring their presence into my daily life. Then in 2012, Cara Bramson, a former student who at the time was working at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, invited me to give a presentation as part of the centers public engagement program. It was the first time that I had talked publicly about my incarcerated relatives and the visual records of their incarceration: family photos, cards, drawings, and paintings on bedsheets.

I had been mulling over doing a project on visuality and prisons but was afraid that it would be too emotionally challenging for my family and me. But after that first presentation, something unexpected happenedsomething that would continue to happen over the years of lecturing and doing research on prison art. People came up to me afterward to describe how they were directly impacted by prisons, how they had been incarcerated themselves or had loved ones in prison, and about the shame and emotional difficulty of talking about these experiences in public. Some shared photos and art that came from prison. This is how the project grewby word of mouth and connecting with others.

I started speaking more frequently at universities, nonprofit centers, and art institutions, in gatherings that were often emotionally loaded for the audiences and for me. Afterward, others would share, often bringing in examples of art made in prison. College students at elite institutions would reveal to me that they had incarcerated relatives back home. The work that I was doing affected my relationships and conversations with family members, too. My incarcerated relatives put me in touch with artists, and family members outside of prison sent me some of their photographs and artwork. Through these experiences, I began to build community around our collective pain and survival, the many millions of families impacted by incarceration, the many millions held captive by prisons and other carceral structures. These encounters raised my awareness of how deep the pain went, how sorrowful it all felt, how vast the injustice and brutality of imprisonment was. Under the grief and rage was a sense of solidarity with others who shared the experience of watching their communities devastated by the various tentacles of what we call mass incarceration, the impact of which goes way beyond prisons.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

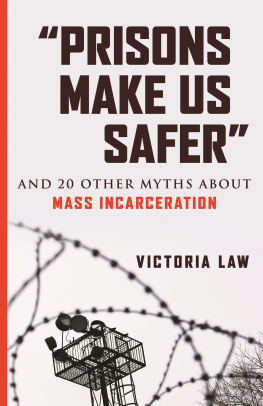

Similar books «Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration»

Look at similar books to Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.