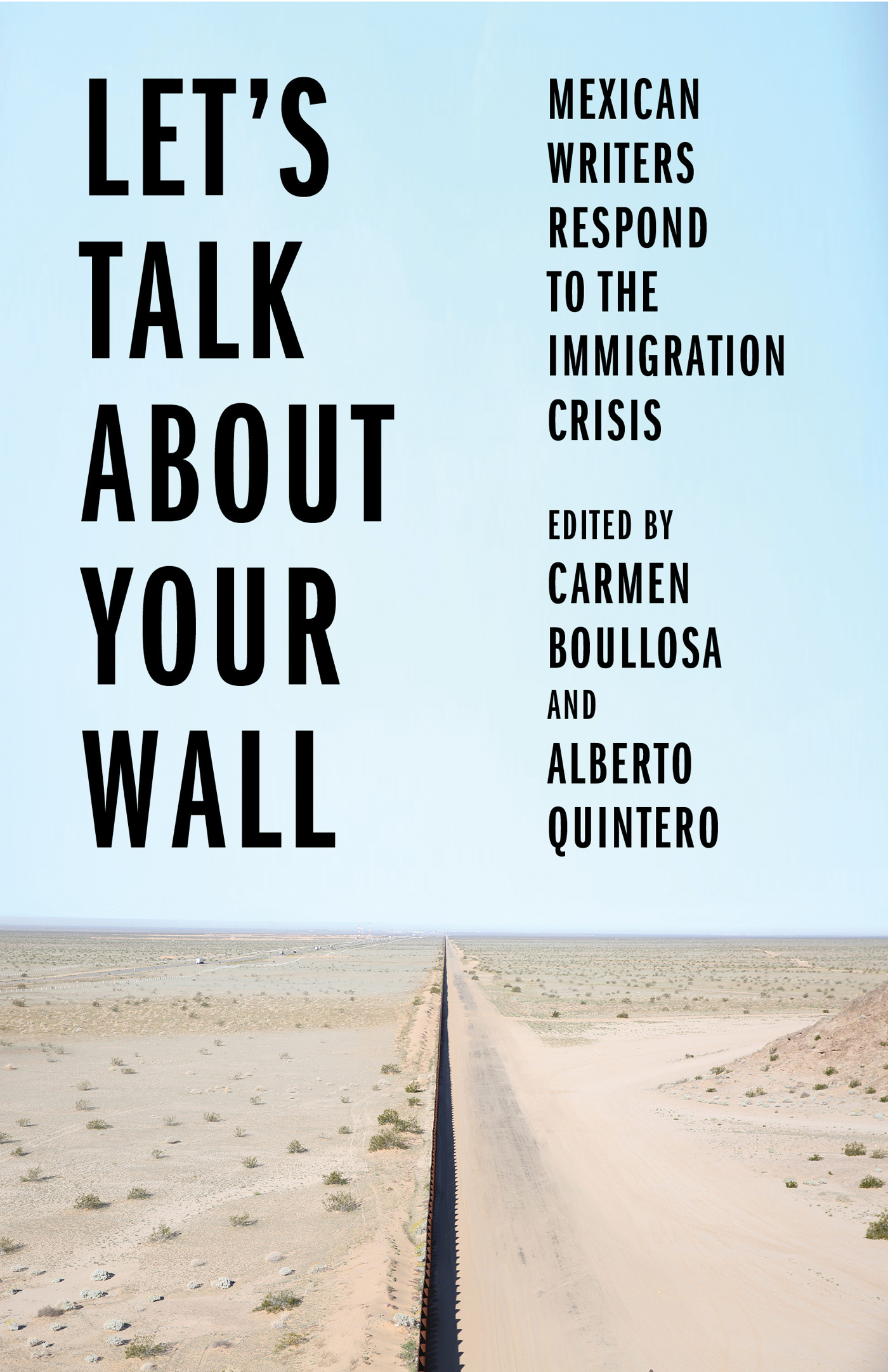

Carmen Boullosa (editor) - Lets Talk About Your Wall

Here you can read online Carmen Boullosa (editor) - Lets Talk About Your Wall full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: The New Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Lets Talk About Your Wall

- Author:

- Publisher:The New Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lets Talk About Your Wall: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lets Talk About Your Wall" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lets Talk About Your Wall — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Lets Talk About Your Wall" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

LETS TALK ABOUT YOUR WALL

LETS TALK ABOUT YOUR WALL

MEXICAN WRITERS RESPOND TO THE IMMIGRATION CRISIS

Edited by

CARMEN BOULLOSA AND ALBERTO QUINTERO

Contents

by Carmen Boullosa

Ysnaya Elena Aguilar

Gil Translated by Ellen Jones

Ren Delgado

Translated by Samantha Schnee

Yuri Herrera

Translated by Lisa Dillman

Claudio Lomnitz

Translated by Jessie Mendez Sayer

Valeria Luiselli and Ana Puente Flores

Jhonni Carr and Romn Lujn

Alejandro Madrazo Lajous

Jean Meyer

Translated by Ellen Jones

Paula Mnaco Felipe

Translated by Ellen Jones

Emiliano Monge

Translated by Victor Meadowcroft

Porfirio Muoz Ledo

Translated by Jessie Mendez Sayer

National Human Rights Commission, Mexico

Translated by Ellen Jones

Guadalupe Nettel

Translated by Sophie Hughes

Juan Carlos Pereda Failache

Translated by Samantha Schnee

Cisteil X. Prez Hernndez

Translated by Lisa Dillman

Leonardo Tarifeo

Translated by Victor Meadowcroft

Eduardo Vzquez Martn

Translated by Ellen Jones

Juan Villoro

Translated by Samantha Schnee

Jorge Volpi

Translated by Samantha Schnee

Yael Weiss

Translated by Jessie Mendez Sayer

Naief Yehya

Translated by Ellen Jones

LETS TALK ABOUT YOUR WALL

Introduction

I was born in 1954, the year in which Operation Wetback forcibly deported a million Mexicans and Mexican Americans from the United States. Though my family lived in Mexico Cityroughly 1,500 miles from our (current) northern frontierand though my family extended far back into Mexican history, the border and el otro lado (the other side) have been omnipresent and complicated factors in my life.

Even before attending kindergarten, la chivera (a smuggler of American commodities) was a familiar presence in my grandmothers home. We treasured the objects the chivera sold us. One of these was my uncle Gustavos portable record player. At the time, there was a ban on the import of American electronics and other products, a legal measure to protect our national industries, but the chivera had supplied us with the newest model, together with some seven-inch acetatesrock-and-roll songs, the real thing, not the diluted Spanish versions that aired on Mexican radio. At preschool, I rejoiced in other chivera merchandise: lunch boxes, pencil cases, Barbies, socks, and some candies that only existed del otro lado.

From time to time my father traveled to the United States, for work. A chemist, he undertook advanced studies in Minneapolis, where he lived with my mother when they were newlyweds. He had mixed feelings about the Americans: deep admiration, and also deep disgust. On the one hand, he took us (his two oldest daughters, not yet in primary school) to baseball games, and back in Mexico he enrolled us both, and my other sisters, in a bilingual school run by American nuns (Ursulines). On the other hand, he despised those Mexican lawyers who fronted for American companies in Mexico, pretending to be the owners, and literally cried each time a big Mexican company was bought by the Americans. Buta third hand?he also helped build Bimbo, a 100 percent Mexican owned industrial bread company that, using American technology, outpaced its chief American competitor, Sunbeam.

The Mexico-U.S. frontier was thus a central fact of my life, as fixed and eternal as were Heaven, Hell, and the Devil in my Catholic girlhood years. It remains so, not least because Im married to an American, and we routinely travel back and forth between Coyoacn and Brooklyn. But in the long sweep of Mexican history the frontier has been anything but fixed.

In the fourteenth century there was no northern frontiercertainly not at the Rio Bravo (or Rio Grande, like Americans call it), as there is now. The first major frontier came with the Aztecs (or the Mexicas, as they named themselves), who were based in Tenochtitln, site of todays Mexico City and founded in 1324. Over the next century, the Mexicas forged a coalition with various city-states, eventually numbering fifty or sixty, collectively populated by roughly seven million people, and constituting itself as an empirean expansionist empire. The Mexicas headed south and north, extending their sway, and exacting tribute through a combination of force, negotiation, and a ceremonial dramaturgy of terror (though they didnt impose their religion or language on their domains). Their northern borderland was roughly 300 miles from the capital and peopled by rebellious subjects who refused to pay tribute or be drawn into the imperial web.

In 1521 the Mexicas were themselves conquered by Hernn Corts and a coalition of their enemies; their imperial domains were absorbed into the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Driven by their lust for land and gold, the Spaniards took up the northward thrust. By 1541 they had reached a point 500 miles from Tenochtitln (and 1,000 miles south of the Rio Bravo). Their 15,000-man army was met and defeated in battle by a coalition of indigenous peoples. The Spanish struck back by burning their towns, destroying their fields and orchards, hanging their leaders, and feeding their aged to the dogs; those left alive were given away as slaves.

For two centuries more, the Spaniards ground northward, repeatedly overcoming resistance, consolidating every victory by building an imperial infrastructure of presidios (fortified garrisons), and constructing a network of churches and convents to house the priests and friars dispatched to convert the now pacified peoples and towns. The farther north they went, the more ferocious were the rebels, fighting for their lives and lands. Displaced denizens of the states of Durango, Coahuila, and Chihuahua looted and burned Spanish outposts. But the frontier kept moving farther north, reaching and surpassing the Rio Bravo, until New Spain included lands that today are occupied by California, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and portions of Colorado, Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Spains claim to this land was, however, contested by Navajos, Apaches, and Comanches. During 1754, a force of 2,000 Comanches attacked the mission of San Sab, in Texas. In 1775, New Mexicos governor wrote that six New Mexicans were buried for each Comanche killed. Comanches were all over Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Santa Fe lived under the Comanche gun.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Spanish empire came up against a force even more formidable than indigenous warriors, that of the rival empires of the English, French, and Dutch. A series of wars and treaties assigned and reassigned various territories. These were reflected in maps that were as much wishful thinking as they were accurate representations of what was happening on the ground. By 1774, at least on paper, New Spain stretched from Patagonia to Alaska.

In truth, the empires hold on its territory was tenuous at best. Not only were there constant assaults from indigenous peoples, but their immense territory was subject to repeated incursions from the British, the French, and the Russians, for instance in the far north fur trade and the great plains. And the establishment of twenty-one missions along the California coast was unable to prevent challenges to Spanish authority from within the empires borders.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Lets Talk About Your Wall»

Look at similar books to Lets Talk About Your Wall. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Lets Talk About Your Wall and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.