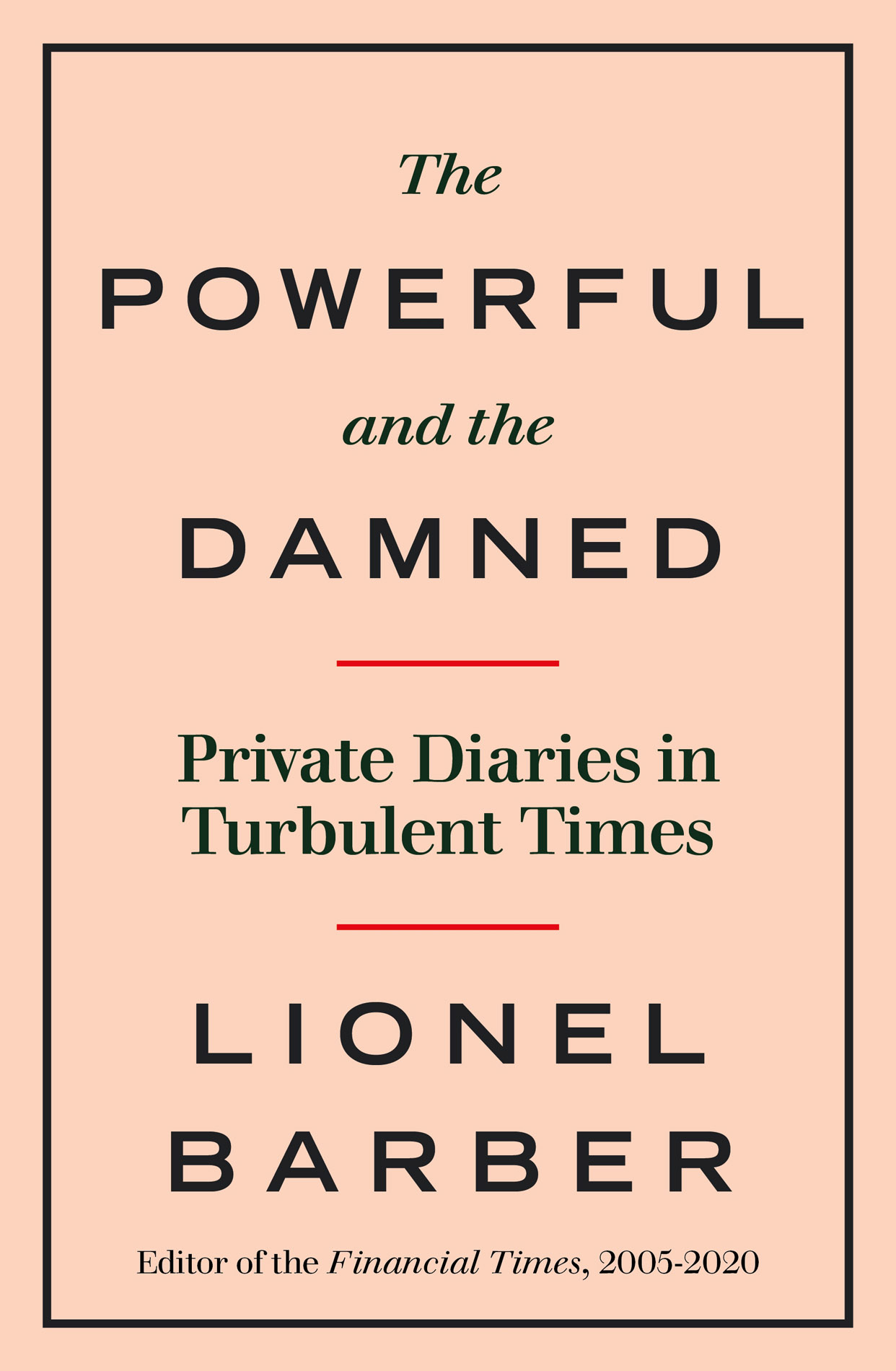

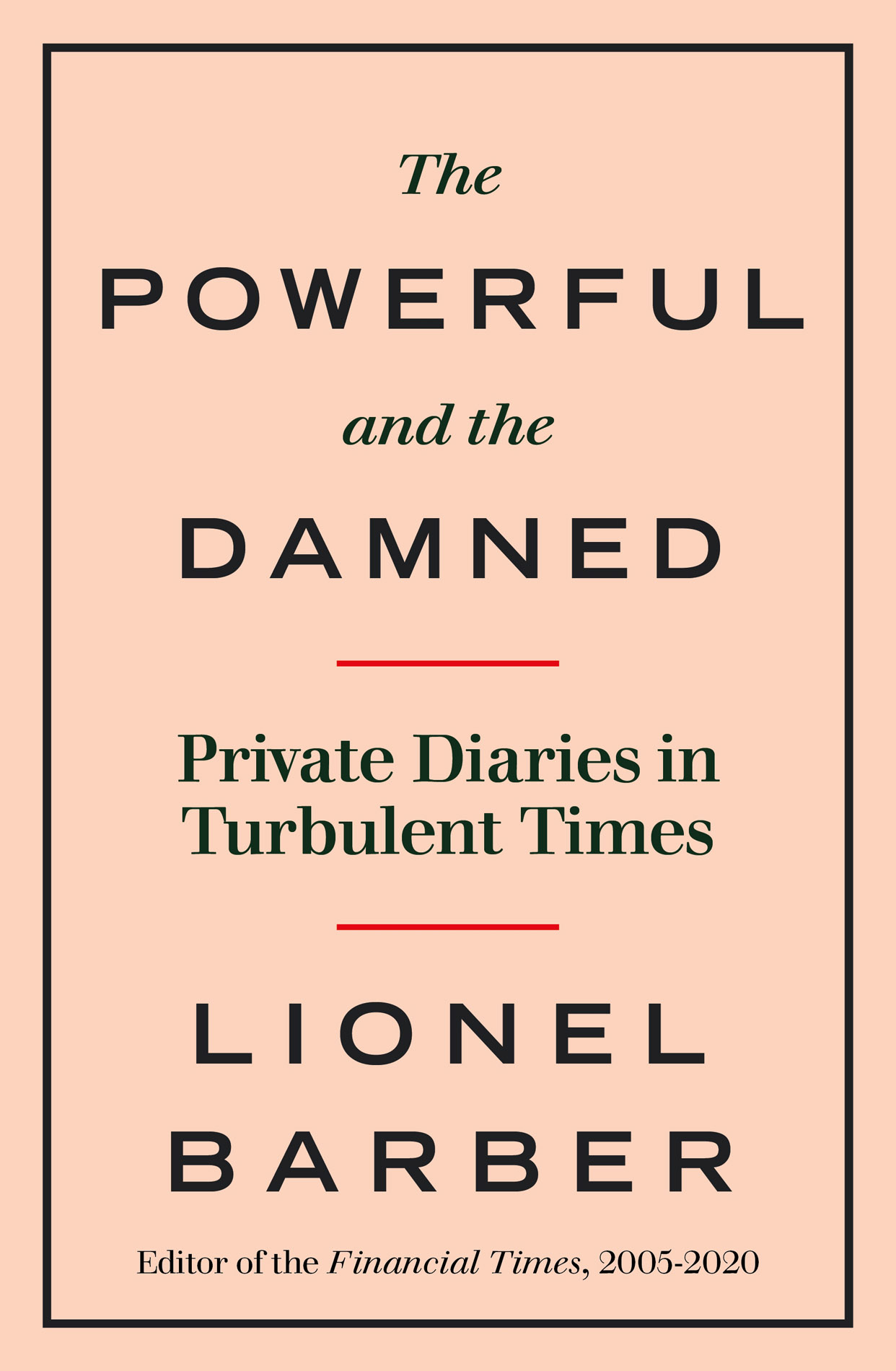

Lionel Barber

THE POWERFUL AND THE DAMNED

Private Diaries in Turbulent Times

Contents

About the Author

Lionel Barber was the Editor of the Financial Times from 2005 until January 2020, widely credited with transforming the FT from a newspaper publisher into a multi-channel global news organisation. During his editorship the FT passed the milestone of 1m paying readers, winning many international awards and accolades for its journalism. The FT was named newspaper/news provider of the year in Britains press awards in 2008, 2017 and 2019. Other prestigious awards include winning submissions to the Loeb and Overseas Press Club in the US and the Society of Publishers in Asia (SOPA) for editorial excellence. As editor, he interviewed many of the worlds leaders in business and politics, including: Barack Obama and Donald Trump, Angela Merkel, Premiers Wen Jiabao and Li Keqiang of China, President of Iran Hassan Rouhani and Presidents Zuma and Ramaphosa of South Africa.

To Victoria

Dramatis Personae

POLITICS

Shinzo Abe, prime minister of Japan (201220)

James A. Baker, White House chief of staff, US treasury secretary, secretary of state (198192)

Tony Blair, UK prime minister (19972007)

Gordon Brown, UK prime minister (200710)

David Cameron, UK prime minister (201016)

Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda (2000 )

Theresa May, UK prime minister (201619)

Angela Merkel, chancellor of Germany (2005 )

Narendra Modi, prime minister of India (2014 )

Benjamin Netanyahu, prime minister of Israel (19969, 2009 )

Vladimir Putin, president of Russia (20002008, 2012 )

Hassan Rouhani, president of Iran (2013 )

Donald Trump, president of the United States (2017 )

BUSINESS AND FINANCE

Sir David Bell, chairman of the FT (19962009)

Lloyd Blankfein, chairman and CEO Goldman Sachs (200618)

Bob Diamond, CEO Barclays Bank (201112)

Mathias Dpfner, CEO Axel Springer (2002 )

John Fallon, CEO Pearson (2013 )

Dick Fuld, CEO Lehman Bros (19942008)

Sir Philip Green, chairman Arcadia Group (2002 )

Tsuneo Kita, chairman and group CEO Nikkei (2015 )

Sir Terry Leahy, CEO Tesco (19972011)

Marjorie Scardino, CEO Pearson (19972012)

Steve Schwarzman, co-founder, chairman and CEO Blackstone (1985 )

Robert B. Zoellick, president of the World Bank (200712)

ROYALTY

HRH Prince Charles, Prince of Wales

HRH Prince Andrew, Duke of York

Mohammed bin Salman, crown prince of Saudi Arabia

JOURNALISM

Paul Dacre, editor of the Daily Mail (19922018)

Roula Khalaf, deputy editor of the Financial Times (201620), editor (2020 )

Alan Rusbridger, editor of the Guardian (19952015)

Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator of the FT (1996 )

DIPLOMACY

Sylvie Bermann, French ambassador to UK (201417)

Fu Ying, Chinese ambassador to UK (20079)

Liu Xiaoming, Chinese ambassador to UK (2009 )

Louis B. Susman, US ambassador to UK (200913)

Preface

My favourite history book is Present at the Creation, Dean Achesons 1969 account of how American leadership forged a new world order after World War II. These private diaries do not pretend to match Achesons majestic memoir, but they do draw inspiration from his sweep and style in our own time of momentous change.

As editor of the Financial Times between 2005 and 2020 the pre-Covid years I had a front-row seat observing the economic and political aftershocks triggered by the global financial crisis. I was an interlocutor to dozens of people in power around the world, each offering unique insights into high-level decision-making and political calculation. And I was an agent of change at the FT, leading the transformation of a print-based product to a fully digital, award-winning news organisation.

The Powerful and the Damned is an eyewitness account of the crisis years when the worlds financial system almost melted down; when liberal democracies were storm-tossed by waves of immigration, populism and terrorism. During this period, traditional media experienced wrenching change as power concentrated around a handful of tech giants led by Apple, Facebook and Google; China, with its own tech giants Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei, emerged as the second superpower alongside the US.

These forces cultural, economic, social and political combined to present a mortal threat to the post-war international order, Achesons order. They eroded public support for traditional parties and institutions in liberal democracies in Europe and the US. And they challenged the FTs own core values of pro-market liberal internationalism and democratic capitalism.

This book aims to convey a sense of these epochal changes through individual portraits of power, via conversation and observation. As editor of the FT, I was privileged to gain access to world leaders in capitals ranging from Beijing, Moscow and Riyadh to Tehran, Tokyo and Washington. I interviewed presidents (Obama, Putin, Trump) as well as leading businessmen and financiers on Wall Street and in the City of London. And I was granted audiences with royalty such as Prince Charles, Prince Andrew and Mohammed bin Salman, the strongman of Saudi Arabia.

These men of power and they are almost all men rather than women are accustomed to wrapping themselves in protective bubbles, surrounded by armies of administrative aides, PR advisers and security guards whose job is to keep prying journalists and the public at a distance. Thanks to my position and the prestige of the FT, I was able to puncture the bubble and engage, up close and personal, with the Powerful and the (occasionally) Damned.

As may be deduced, I chose at the outset to be a working journalist and reporter, close to the news rather than being cooped up in the editors office. My every hour in London was devoted to producing gold standard journalism. But I also consciously made time to travel, working with members of the FTs network of more than 100 foreign correspondents, to broaden my perspective.

During my editorship, the FT won acclaim for its journalism and its ever expanding readership, but we also made mistakes. We fell short I fell short in failing to appreciate popular disenchantment with authority and elites in the wake of the financial crisis. Identity politics and resentment over entrenched economic inequality paved the ground for Brexit. We were not responsible for losing the 2016 referendum, but by and large we missed the story. Being an establishment newspaper is no excuse. It was a failure of imagination, and we learnt our lesson.

Nevertheless, I would maintain, many of the FTs big calls were right, on markets, the euro and a series of high-risk, high-reward investigations which culminated in the exposure of Wirecard, Germanys equivalent of the Enron scandal. Wirecards collapse, six months after I stepped down as editor, vindicated three years and more of original reporting which exposed abuse of power and deep-rooted fraud in a Dax 30 company. Perhaps even more significantly, it established the importance of facts in a supposedly post-truth age.

Next page