The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

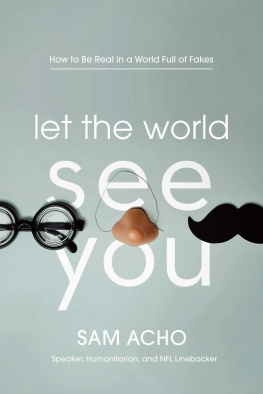

Dear white friends, countrypersons: welcome. Pull up a chair.

Consider this book an invitation to the table. Its a special tablebut dont worry, this isnt one of those uptight, wheres-your-VIP-reservation places, rather a come-as-you-are joint for my white brothers and sisters and anyone else inclined to join us. The room where this table sits is a safe space, by which I mean a space to learn things youve always wondered about, a place where questions you may have been afraid to ask get answered. For all of you who lack an honest black friend in your life, consider me that friend.

My arms are open wide, friends. My heart, too.

Before I get into more of what to expect from the book, I want to share a few things about myself. Ive been navigating the lines between whiteness and blackness all of my lifestarting with growing up in Dallas, Texas, as the son of Nigerian immigrants. My homelife was steeped in Nigerian culture, rather than black American culture; I only got that on Sundays and on Wednesdays at church. My surroundings, meanwhile, were disproportionately white, from my upper-class suburban neighborhood to the private school I was fortunate to attend. I became Manny to all the kids who decided my real name was too foreign.

I wasnt unaware of racism, growing up. My home state, as you may know, is the birthplace of Juneteenth, a holiday that celebrates the day enslaved people in Texas discovered theyd been set freethe last group of black people to find out. Its a day that, among other things, calls attention to the states long Confederate history. There might not have been any Lost Cause soldiers terrorizing my neighborhood, but from the time I was nine or ten years old, I knew Id experienced racism. It wasnt that overt, call-you-the-N-word-to-your-face racism. It was more subtle. Like, for example, the uncountable times some kid in elementary school or middle school or high school plopped down at my lunch table and, after hearing me recount some playground feat, said, You dont even talk like youre black, or You dont sound black, or You dont even dress like youre black. Or the ever-popular Youre like an Oreo: black on the outside, white on the inside.

I was offended, but I also thoughtMaybe theyre right? Maybe Im not black enough? Thank you if youretelling me I sound smart but then, are you saying black people cant be smart? Let me tell you, kid Emmanuel was working on an identity complex.

You shouldve seen me when I got to the University of Texas and found myself surrounded by more black people than I ever had been. Yo, I realized, these are my people. Im home at last. You know when Tarzan finally met some humans and was like, Oh, Im a human? It was like that. Those early college years were the first time I understood what it means to be a black man in America. Part of this meant realizing how my childhood had given me misguided impressions about my own people. I had been fed the same stereotypical stuff about black people as the white kids around me, and I hadnt been immune: they had me under the impression that the only real way to be black was to be Nelly circa 2002, minus the Band-Aid under the eye. Finally surrounded by so many different expressions of blackness, I knew I was fine the way I was. But I started to wonder: If I, a first-generation-American black man, could be taught to believe distorted things in such a short time, how much easier is it for a white person to believe them?

Today, Im grateful for all my experiences, because they were all a kind of lesson. Ask anybody: to be fluent in a language, you have to study abroad. I studied Spanish all four years of high school, but I was never fluent because I never set foot in Spain. Well, my childhood was one big study abroad in white culturefollowed by studying abroad in black culture during college and then during my years in the NFL, which I spent on teams with 8090 percent black players, each of whom had his own experience of being a person of color in America. Now, Im fluent in both cultures: black and white.

The book youre reading is what I want to do with that perspective.

WERE IN THE MIDST of the greatest pandemic in recent times, which has the potential to be the greatest pandemic of all time. (Friends, wear your masks and wash your hands.) However, the longest-lasting pandemic in this country is a virus not of the body but of the mind, and its called racism. Im not sure if we can cure racism completely, but I also believe that as we rush to find a vaccine for COVID-19, we should be pursuing with equal determination a cure for the virus of racism and oppression. The ultimate logic of racism, Martin Luther King Jr. once said, is genocide. I dont mean to be the Bad News Bears, but we are living in an America that necessitated the Black Lives Matter movement. A country in which the simple declaration that people who look like me are worth saving has become controversial.

Enough. I want to be a catalyst for change, to help cure the systemic injustices that have led to the tragic deaths of too many of my brothers and sisters; prisons popping up like fast-food chains; inequalities in health care and education; the forced facts of who gets to live where; the ingrained ignorance of Americans who cant see beyond skin color. I believe an important part of the cure, maybe the most crucial part of it, is to talk to each other.

Let me take a second to break down what I mean. I dont mean chatting about whatever; I mean a two-way dialogue based on trust and respect, full of information exchanged and perspectives shared. The goal here is to build relationshipsand, ultimately, to help us recognize each others humanity. Id bet some Dallas Cowboys season tickets that its tough, if not impossible, to hold bigoted thoughts about someone whose humanity you recognize. Id double down: it would take some next-level self-deluding to discriminate against someone you respect enough to listen to.

IN THESE PAGES, the only bad question is the unasked question. Youll see that each chapter starts with a question, each of which is from a real email Ive received in response to my video series. (Same title as this book, if you got here without watching.) I appreciate every one of them, because wherever the askers are coming from, they came to learn.

If things go the way I want, you will leave this book with an increased understanding of race. You will have more empathy and grant people more grace. And if you have more empathy and are more gracious, then youll be less judgmental. And if youre less judgmental, then your judgment is less likely to play itself out in racism.

Now, there are degrees of racism. If youre reading this, I imagine youre not a white-hood-wearing, Confederate-statue-defending, Dukes of Hazzardidolizing, tiki-torch-toting, N-word-barking first-degree racist. However, you might fall between the second or third degree, meaning someone who is not overtly racist but is on a spectrum between a person who is a little racially insensitive or ignorant and someone who holds deeply ingrained negative ideas about people of other races and ethnicities. Even if none of the above descriptions fit you, you might know someone they do fit.