T his book is the outcome of serendipity and timeliness to address the loss of memory about past pandemics, written while we were in the middle of one. In writing it, I offer two core arguments. First, the cholera, plague and influenza pandemics between 1817 and 1920 need to be placed firmly in the global historiography of this period, currently dominated by themes such as nationalism, imperialism, capitalism or globalization. Second, I argue that the Age of Pandemics has been forgotten in the country most affected by itIndiaand that there is value in remembering it as a major event just as the Black Death plague pandemic of the fourteenth century is registered in European consciousness to this day. This is important because building such collective memory is useful to counter current and future pandemics.

My approach is partly inspired from the field of demographic history. My interest in this subject began by reading the pioneering work of Tim Dyson, whom I have never met, but with whom I have had the good fortune of interacting over email in recent years. I also learnt a lot from the work of researchers who have devoted large parts of their careers to understand the history of epidemics and health in IndiaIra Klein, David Arnold, Mark Harrison, Ian Catanach, Mridula Ramanna and many others. I would particularly like to thank Maura Chhun for promptly sharing her doctoral research on Influenza in India and other relevant resources.

Remote research during a lockdown was possible only because of excellent digital archives maintained by the Wellcome Collection, National Library of Scotland (Medical History of British India), the Edinburgh Research Archive, the Visual Plague Project at the University of Cambridge, Archive.org, ProQuest Times of India Digital Database, South Asia Archives and Ideas of India Archive. The pictures from the Wellcome Collection are courtesy of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial license (CC BY-NC 4.0). The book also benefited from excellent research assistance provided by Aasha Eapen and Mrinal Tomar. While writing, I have used the old and new names of places interchangeably. The statistical analysis is provided in a separate document, available online, and mentioned in the Notes section.

I would like to thank Yogesh Kalkonde for sharing an important oral history he collected in Gadchiroli district in central India on the 1918 pandemic. To him and Ambarish Satwik, I owe a debt of gratitude for taking out time from their busy hospital schedules in the middle of a pandemic to provide feedback on the draft chapters. I also benefited from detailed comments by Tirthankar Roy and Maura Chhun.

Many others have contributed in different ways: Ravi Abhyankar, Sanghamitra Chatterjee, Lucy Taksa, Patrick French, Jeemol Unni, Amol Agrawal, Aparajith Ramnath, Aashish Gupta, Basav Biradar, C.J. Kuncheria, Yunus Lasania, Y.B. Satyanarayana, Aanchal Malhotra, Abhi Sanghani, Sudev Sheth, Amrita Roy, Sandeep Badole, Ankur Sarin, Jeevant Rampal and Sukanya Basu. Presentations in the CASI-UPenn and EHDR webinar series and discussions with Ed Glaeser and his Dev-Urban group prompted great feedback.

Swati Chopra encouraged and edited, motivated and manoeuvred this book with infectious enthusiasm, as did the wonderful team at Harper Collins. I thank Gavin Morris and Bonita Shimray for designing the cover, and Chandna Arora for her work on the copy edits. Friends and family chipped in from time to time with little known nuggets. During the lockdown, my father, Vasudev Tumbe, eased into retirement and reading, and my mother, Sudha Huzurbazar Tumbe, into prolific writing. Both of their newly acquired skills were valuable in improving this book. My wife, Divya, survived the lockdown with plants, wit, humour and her own wonderful writing, all of which added to this project, as did my son, Siddhartha, who prompted the first spark.

Good architecture provides a stimulus to thinking, or so I feel after writing this book in Louis Kahns awe-inspiring red-brick campus of the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. The tallest point among those red bricks is the Vikram Sarabhai Library, whose staff provided outstanding support for my research, locating rare material through their global inter-library ties. This remarkable effort was due to the leadership of Dr H. Anil Kumar, librarian, colleague and friend. His untimely death on 17 July 2020, the day he turned fifty-three, was a personal loss for many of us and brought home the painful reality of the pandemic. We miss you, Anil. This book, sitting on library shelves and elsewhere, is dedicated to you and your passion for books and libraries, both of which make this world a more beautiful place.

Were there pandemics in the past as well? asked Siddhartha, my eight-year-old son.

I paused nervously, registering the fact that the word pandemic had entered his vocabulary at such a young age.

Well, there was something known as influenza , I began. But before I could complete, he pulled out Tintin and the Picaros from his prized collection and opened page sixteen of the Egmont edition. Sure enough, a villainous army officer on that page laments the cancellation of Tintins trip due to influenza in Europe.

Taken aback by the effortlessness with which he had spotted a word that I had assumed he would never know, I said nothing further, until he pressed on, and asked me, Go on, tell me more.

Our dead are never dead to us until we have forgotten them

Mary Evans/George Eliot

O nce upon a time, we barely lived before we died. We would celebrate on average only twenty-five birthdays in our lifetimes and we rarely grew old enough to see our grandchildren. Mass mortality through war, famine, natural disasters and epidemics was a way of life. We began to live longer only when we fought fewer wars, understood how to prevent famines, grew resilient to natural disasters, and learnt how to control the spread of disease.

Different parts of the world began their journeys out of mass mortality at different times. In India, this journey began in 1920. It is an incredible achievement that stands in stark contrast to the remarkable century that preceded it.

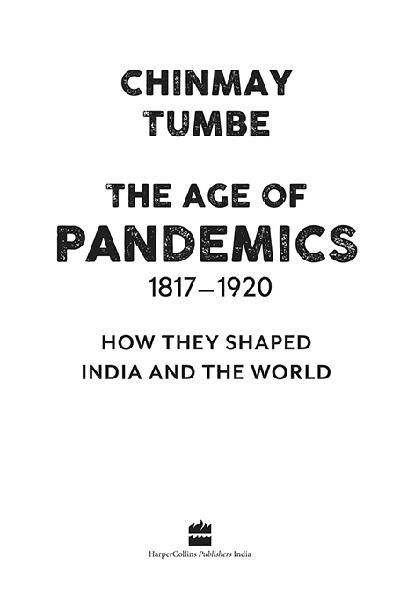

Between 1817 and 1920, over 70 million people in the world died from pandemics, a figure far greater than the number of people killed by wars. Never heard about this? Perhaps it is because we had collectively forgotten about pandemics till the words COVID-19, lockdown and social distancing came into our consciousness.

Epidemics and Pandemics

One of the fundamental laws of mortality in the past century has been that over time, and especially as we get richer, we tend to die in smaller proportions from communicable diseases. The list of such communicable diseases is long and even seasoned medical practitioners routinely consult their books for diagnosis.

Malaria has been the deadliest communicable disease in history, transmitted to humankind through female Anopheles mosquitoes, for several millennia. Those mosquito bites that you feel on your hands, those desperate claps to kill the buzzing irritation you hear, those stagnant water pools you see and smell with great dismay, provide a fulsome sensory experience even before getting the disease. I have vivid memories of open-air musical performances in my boarding school held in the evenings, less for the music and more for the organized mosquito-killing sprees we conducted through whispers and silent claps, with the sole objective of saving our hands and legs. We spared no singer, male or female, young or old, Hindustani or Carnatic; our attention was unabashedly directed towards the mosquitoes because the music, evidently, did not kill them.