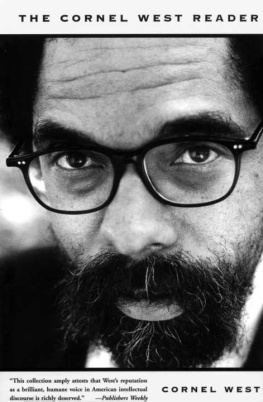

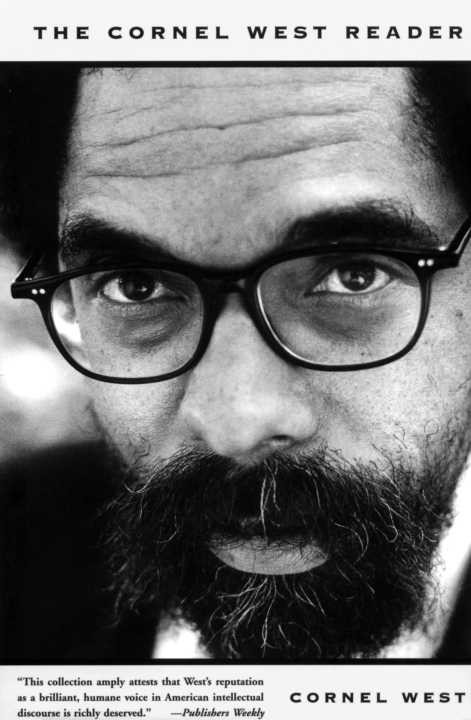

The

CORNEL WEST

Reader

BOOKS ALSO BY CORN EL WEST

Prophesy Deliverance! An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity (1982)

Theology in the Americas: Detroit II (1982)

(Co-Editor)

Post-Analytic Philosophy (1985)

(Edited with john Rajchman)

Prophetic Fragments (1988)

The American Evasion of Philosophy (1989)

Out There: Margin alization and Contemporary Cultures (1990)

(Co-Editor)

The Ethical Dimensions of Marxist Thought (1991)

Breaking Bread (1991)

(with bell hooks)

Prophetic Thought in Postmodern Times (1993)

Prophetic Reflections (1993)

Race Matters (1993)

Keeping Faith: Philosophy and Race in America (1993)

James Snead, White Screens, Black Images (1994)

(Edited with Colin McCabe)

Jews & Blacks : Let the Healing Begin (1995)

(with Michael Lerner)

The Future of the Race (1996)

(with Henry Louis Gates, -.)

Struggles in the Promised Land (1997)

(Edited with lack Salzman)

Restoring Hope (1997)

The War Against Parents (1998)

(with Sylvia Ann Hewlett)

The Future of American Progressivism (1998)

(with Roberto Mangabeira Unger)

The Courage to Hope: From Black Suffering to Human Redemption (1999)

(Edited with Quinton Hosford Dixie)

... WRITE ABOUT THIS YOUNG MAN SQUEEZING DROP BY DROP THE SLAVE OUT OF HIMSELF AND WAKING ONE FINE MORNING FEELING THAT REAL HUMAN BLOOD, NOT A SLAVE'S, IS FLOWING IN HIS VEINS.

-Anton Chekhov

To BE A MUSICIAN IS REALLY SOMETHING. IT GOES VERY, VERY DEEP. MY MUSIC IS THE SPIRITUAL EXPRESSION OF WHAT I AM-MY FAITH, MY KNOWLEDGE, MY BEING.... WHEN YOU BEGIN TO SEE THE POSSIBILITIES OF MUSIC, YOU DESIRE TO DO SOMETHING REALLY GOOD FOR PEOPLE, TO HELP HUMANITY FREE ITSELF FROM ITS HANG-UPS.

-John Coltrane

TO THE MEMORY AND LEGACY OF MY MODERN ARTISTIC SOUL MATES

John Coltrane

Federico Garcia Lorca

Franz Kafka

Paul Celan

T nnessee Williams

Giacomo Leopardi

Samuel Beckett

Sarah Vaughan

Muriel Rukeyser

Thomas Hardy

.Nikos Kazantzakis

Toni Morrison

AND ABOVE ALL

Anton Chekhov

xiii

xv

I AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL PRELUDE

II MODERNITY AND ITS DISCONTENTS

III AMERICAN PRAGMATISM

IV PROGRESSIVE MARXIST THEORY

V RADICAL DEMOCRATIC POLITICS

VI PROPHETIC CHRISTIAN THOUGHT

VII THE ARTS

VIII RACE AND DIFFERENCE

IX POSTSCRIPT

THE PRIMARY AIM OF this reader is to lay bare the basic structure of my intellectual work and life. This reader takes the form of a variety of voices and an array of interests that focus on two fundamental themes: the art of living and the expansion of democracy.My painful quest for wisdom is an endless journey that tries to delve into the darkness of my soul to create a more mature and compassionate person. My political project of deepening democracy in the world is a perennial process of highlighting the plight of the wretched of the earth and broadening the scope of human dignity.This volume not only represents the progression of my thought but also consists of my reflections on it. I chose these pieces rather than others from my corpus because they best represent the crucial moments of an evolving whole. This whole-fraught with tensions and contradictions-reflects my attempt to shatter my own parochial limits and provincial shortcomings. My efforts to understand myself are inseparable from understanding what it means to be human, modern, American, black, male and straight in global and local contexts. And since this text was put together at a unique moment in my life-when Eros erupted and life quickened-it marks a turning point in many ways.This volume will, I hope, keep these ideas alive in the mind of the reader so that they may be debated and refined. In my travels as a speaker, I continue to be struck by the persistence of certain themes and concerns of my audiences. These include, of course, race but, more generally, focus on questions of the good and how one might lead a meaningful life-a life in dialogue with history, connected to community-without falling into despair. This reader should serve as a reproach to easy despair and an inspiration to those who wish to travel with me on this quest.I would like to thank my agent, Gloria Loomis, for her extraordinary care and support of my work. I would like to acknowledge the visionary and superb editorial work of my friend and brother Tim Bartlett. This book exists, in part, because of him. And I would like to thank my friends and sisters Vanessa Mobley and Libby Garland for their excellent editorial assistance. It was sheer fun to work with them. Finally, I would like to congratulate my dear mother upon receiving a well-deserved recognition as an exemplary teacher and principal in the form of the new Irene B. West Elementary School in Sacramento, California.

To BE HUMAN, MODERN AND AMERICAN As WE APPROACH THE deathbed of this ghastly century, an uncanny sense of terror and hope should haunt us. As at the sad funeral of a loved one, we remember the cruel circumstances and heroic energies of those who are now the culinary delight of terrestrial worms. My own work and life have always unfolded under the dark shadows of death, dread and despair in search of love, dialogue and democracy. I am first and foremost a blues man in the world of ideas-a jazz man in the life of the mind-committed to keeping alive the flickering candles of intellectual humility, personal compassion and social hope while living in our barbaric century. I am primarily a dramatist of philosophic notions and historical narratives that partake of blood-drenched battles on a tear-soaked terrain in which our lives and deaths are at stake.My work is a feeble attempt to understand and respond to the guttural cry that erupts from the depths of the soul of each of us. The existential quest for meaning and the political struggle for freedom sit at the center of my thought. My writings focus on the specific and contemporaneous ways in which we grapple with concrete and universal issues of life and death, oppression and resistance, joy and sorrow.I am a Chekhovian Christian with deep democratic commitments. By this I mean that I am obsessed with confronting the pervasive evil of unjustified suffering and unnecessary social misery in our world. And I am determined to explore the intellectual sources and existential resources that feed our courage to be, courage to love and courage to fight for democracy. Three related and fundamental questions motivate my writings: What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be modern? What does it mean to be American?My perennial wrestling with these overwhelming queries, which suffuses the essays in this volume, is rooted in my terrifying experience and constant awareness of the radical contingency and fragility of life. I find the incomparable works of Anton Chekhov-the best singular body by a modern artist-to be the wisest and deepest interpretations of what human beings confront in their daily struggles. His salutary yet sad portraits of the nearly eight thousand characters in his stories and plays-comparable only to Shakespeare's variety of personages-provide the necessary ground, the background noise, of any acceptable view of what it means to be human. His magisterial depiction of the cold Cosmos, indifferent Nature, crushing Fate and the cruel histories that circumscribe desperate, bored, confused and anxiety-ridden yet love-hungry people, who try to endure against all odds, rings true for me. Furthermore, I find inspiration in his refusal to escape from the pain and misery of life by indulging in dogmas, doctrines or dreams as well as abstract systems, philosophic theodicies or political utopias.In short, Chekhov provides exemplary tragicomic dramas, subject to multiple interpretations, for serious thinking and wise living. His art yields the most intelligent reflection and depiction of the limits of critical intelligence in confronting our worldly existence. Yet his acute sense of the incongruity in our lives is grounded in a magnificent compassion for each of us. Chekhov understands what drives the cynic without himself succumbing to cynicism. He appreciates the childlike fantasies of the sentimentalist without yielding to the childishness of sentimentalism. Like the best blues and jazz artists, he enacts melancholic yet melioristic indictments of misery without concealing the wounds inflicted or promising permanent victory. He stays in touch with the everyday realities of ordinary people and highlights our peculiar wrestlings with appearance and reality, opinion and knowledge, illusion and truth-of beauty, love and the collective struggle for a decent society. Like his literary ancestors Sophocles and Shakespeare and his twentieth-century progeny Kafka and Beckett, Chekhov leads us through our contemporary inferno with love and sorrow, but no cheap pity or promise of ultimate happiness.I remain a Christian-despite Chekhov's agnosticism-primarily because the concrete example of the love and compassion of Jesus rendered in the biblical Gospel narratives constitutes the most absurd and alluring mode of being in the tragicomic world. In this way, I stand in the skeptical Christian tradition of Montaigne, Pascal and Kierkegaard-figures in touch with (and often tortured by) an inescapable demon of doubt inscribed within their humble faith. This tradition enables me feebly to love my way through the absurdity of life and the darkness of history. Their bold intellectual thought and courageous existential witness have little to do with much or most of institutional Christianity or any organized religion. In fact, Erasmus is one of the few towering Christian figures who could exemplify this thought and witness and remain in the established church of his day.My Chekhovian Christian conception of what it means to be human puts a premium on death and courage. To be human is to suffer, shudder and struggle courageously in the face of inevitable death. To think deeply and live wisely as a human being is to meditate on and prepare for death. The quest for human wisdom requires us to learn how to die-penultimately in the daily death of bad habits and cruel viewpoints and ultimately in the demise of our earthly and temporal bodies. To be human, at the most profound level, is to encounter honestly the inescapable circumstances that constrain us, yet muster the courage to struggle compassionately for our own unique individualities and for more democratic and free societies. This courage contains the seeds of lived history-of memory, maturity and melioration-in the face of no guaranteed harvest. Hence, my view of what it means to be human is preeminently existential-a focus on particular, singular, flesh-and-blood persons grappling with dire issues of death, dread, despair, disease and disappointment. Yet I am not an existentialist like the early Sartre, who had a systematic grasp of human existence. Instead, I am a Chekhovian Christian who banks his all on radical-not rational-choice and on the courage to love enacted by a particular Palestinian Jew named Jesus, who was crucified by the powers that be, betrayed by cowardly comrades and misconstrued by corrupt churches that persist, and yet is remembered by those of us terrified and mesmerized by the impossible possibility of his love.My Chekhovian Christian viewpoint is idiosyncratic and iconoclastic. My sense of the absurdity and incongruity of the world is closer to the Gnosticism of Valentinus, Luria or Monoimos than that of historic religious orthodoxies-yet, unlike them, it retains a deep sense of history. My intellectual lineage goes more through Schopenhauer, Tolstoy, Rilke, Melville, Lorca, Kafka, Celan, Beckett, Soyinka, O'Neill, Kazantzakis, Morrison and, above all, Chekhov (all great dramatic poets of death, courage and compassion) than most theologians and philosophers. And, I should add, it reaches its highest expression in music-as in Brahms's Requiem and Coltrane's A Love Supreme. Music at its best achieves this summit because it is the grand archaeology into and transfiguration of our guttural cry, the great human effort to grasp in time (with the most temporal of the arts) our deepest passions and yearnings as prisoners of time. Profound music leads us-beyond language-to the dark roots of our scream and the celestial heights of our silence.To be modern is to have the courage to use one's critical intelligence to question and challenge the prevailing authorities, powers and hierarchies of the world. Despite my Chekhovian Christian conception of what it means to be human-a view that invokes premodern biblical narratives-I am a quintessentially modern thinker in that I weave disparate narratives in ways that result in novel forms of self-exploration and self-experimentation. To be modern is to live dangerously and courageously in the face of relentless self-criticism and inescapable fallibilism; it is to give up the all-too-human quest for certainty and indubitability owing to the historicity of our claims. Yet to give in to sophomoric relativism ("Anything goes" or "All views are equally valid") is a failure of nerve, and to succumb to wholesale skepticism ("There is no truth") is a weakness of the will and imagination. Instead, the distinctive mark of modernity is to pursue the treacherous trek of dialogue, to wager on the fecund yet potentially poisonous fruits of fallible inquiry, which require communicative action, risk-ridden conversation, even intimate relation.My conception of what it means to be modern is shot through with a sense of the dialogical-the free encounter of mind, soul and body that relates to others in order to be unsettled, unnerved and unhoused. This experience of dialogue-the I-Thou relation with the uncontrolled other-may result in a dizziness, vertigo or shudder that unhinges us from our moorings or yanks us from our anchors. This thoroughly modern lightness of being-produced, in part, from the innovations of modern science and technology or improvisations of modern music and the artsis both frightening and energizing. This loss of our footing and gain of our freedom compel us to acknowledge that the very meaning of being modern may be the lack of any meaning, that our quest for such meaning may be the very meaning itself-without ever arriving at any fixed meaning. In short, the hermeneutical circle in which we find ourselves, as historical beings in search of meaning for ourselves, is virtuous, not vicious, because we never transcend or complete the circle. Like Sisyphus, we go endlessly up and down with noble aims and aspirations, but no ultimate harmony or achieved wholeness.My Chekhovian Christian conception of what it means to be modern focuses on the night side of modernity, the underside of our contemporary predicament. Therefore I highlight the forms of self-making and self-creating of those whose suffering is often rendered invisible by the Enlightenment discourse on the light of natural reason and the Romantic preoccupation with imaginative transformation. Of course, to be deeply modern is to be critical of the blindness of certain forms of critical intelligence and to imagine forms of transformation far beyond Romantic versions of imaginative transformation. Therefore my critiques of modernity extend, refine and expand modern consciousness and practice. Yet my Chekhovian Christian perspective of what it means to be modern cuts even deeper. It gives up on the very possibility of arriving at a definitive, definite-or dogmatic-end point of modernity. Instead, it stresses the very means by which and procedures through which we pursue our aims. In short, it highlights the dialogical process and democratic practices through which we pursue the very ends we cherish.To be American is to be part of a dialogical and democratic operation that grapples with the challenge of being human in an open-ended and experimental manner. Although America is a romantic project in which a paradise, a land of dreams, is fanned and fueled with a religion of vast possibility, it is, more fundamentally, a fragile experiment-precious yet precarious-of dialogical and democratic human endeavor that yields forms of modern self-making and self-creating unprecedented in human history. From Thomas Jefferson to Elijah Muhammad, Geronimo to Dorothy Day, Jane Addams to Nathanael West, it holds out the possibility of self-transformation and self-reliance to New World dwellers willing to start anew and recast themselves for the purpose of deliverance and betterment. This purpose requires only a restlessness, energy and boldness that galvanizes people to organize and mobilize themselves in a way that makes new opportunities and possibilities credible and worth the effort.To be American is to give ethical significance to the future by viewing the present as terrain capable of transcending any past and thereby arriving at a new identity and community. From the revolutionary hopes of European settlers on Amerindian land and bodies to millennial hopes of Mormons and Baptists against Old World Protestant establishments, Americans give weight and gravity to the possibility that future prospects can trump present troubles. From Emerson's Yes to tomorrow against the defeat of today through Whitman's song of the open road given the weight of the fixed form and ancient verse to James's and Dewey's obsession with fruits, consequences and effects against Descartes's stress on origins, beginnings and starting points, American culture accentuates what is to come, what is not yet as opposed to what is and what has been. Of course, such a futuristic orientation often degenerates into an infantile, sentimental or melodramatic propensity toward happy endings, so that dreams of betterment downplay the dark realities of suffering in our midst. In this way, American discourses on innocence, deliverance or freedom overlook the atrocities of violence, subjugation or slavery in our past or present. To be American is to downplay history in the name of hope, to ignore memory in the cause of possibility. Our great truthtellers-mainly artists-remind us that history will haunt us and memory should keep us honest. Melville, Hawthorne, Twain, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, O'Neill, Tennessee Williams, Theodore Dreiser, Toni Morrison, Thomas Pynchon, Lorraine Hansberry and others spin out candid narratives and painful truths about our alltoo-human complicity with evil and evasion of dark realities, which no country or social experiment can ignore without danger. My Chekhovian Christian perspective tries to remain true to the heart-wrenching tales and truths of such American artists. They remind us of the all-too-human forms of mendacity and hypocrisy pervasive in American life.To be American is to raise perennially the frightening democratic question: What does the public interest have to do with the most vulnerable and disadvantaged in our society? This query of democratic import goes back to Cleisthenes of 508 B.C. in Athens. Shouldn't democracy be a form of plebodicy-not theodicy-that focuses our attention on the unjustified suffering and unnecessary social misery of ordinary human beings here and abroad? And yet isn't American democracy one in which arbitrary power is not fully curtailed and, hence, the political, corporate and financial elites-unregulated by substantive public accountability-wield forms of power that cause pain and grief for fellow citizens that need not be? Are not democratic practices historically transgressive and even subversive actions of heroic citizens that transform inherited forms such that their decency and dignity are recognized by elites? Is not the grand paradox of American democracy at its inception that the people are distrusted and contained, their power dispersed and diluted so that elites may prosper at the expense of workers' power, women's power and especially black, brown, yellow and red power? Can America ever really be truly America without a full-fledged multiracial and multi- gendered democracy-a democracy that flourishes in the political, economic, cultural and even existential spheres? Can the dignity of everyday people thrive in an oligarchic and plutocratic economy? Can American democracy be true to its ideals without a nonracist and nonsexist culture and society? Does not pervasive homophobia require a nonheterosexist social arrangement? These are the challenging questions of Whitman, Dewey, Addams, Baldwin, Lorde and Martin Luther King, Jr.Can America, the last grand empire of the twentieth century, meet such a challenge? Is a multiracial and multisexual political democracy the best we-or humankind-can do? Is economic democracy in a global economy a pipe dream? Is the globalization of democracy a fantasy in the face of unaccountable multinational corporate power? Is the vision of existential democracy-of Maurice Maeterlinck, Walt Whitman and Anton Chekhov-a mirage? Is it possible that democracy can be a way of being in the world, not just a mode of governance circumscribed by corporate power and monied interests? These are the great questions of the twenty-first century, the grand challenges of the next wave of democratic possibility. Have we reached the limits of the American religion of possibility? Do class, race and gender hierarchy have the last word on how far democracy can go in our time? My Chekhovian Christian viewpoint says No! No! No! But maybe. Indeed, surely, if we fail to speak our fallible truths about the social misery in our midst here and abroad, if we fail to expose the vicious lies about our past and present and if we fail to bear our imperfect yet courageous witness of love and democracy at the birth of our new century! Let it be said of us centuries from now that we were bold and visionary in our efforts to live with courage and compassion in the face of death, to pursue dialogue over and against the overwhelming odds of misunderstanding and violence and to fight for old and new forms of democracy at the beginning of a century that may well produce novel forms of barbarism and bestiality if we fail to respond to the tests of our time.The Chekhovian Christian perspective put forward in this reader is my testament of hope for the twenty-first century. The words, sentences and paragraphs are but linguistic marks that track my journey of blood, sweat and tears, which tries to achieve and enact the best of what it means to be human, modern and American. These marks often fall far short of the high mark-and pale in the face of good music-yet they point toward a certain kind of musical life that painfully pursues a compassionate individuality and courageously struggles for a more free and democratic world. This reader is my attempt to transfigure our guttural cry into a call to care-for causes bigger and grander than our own precious cry.

Next page