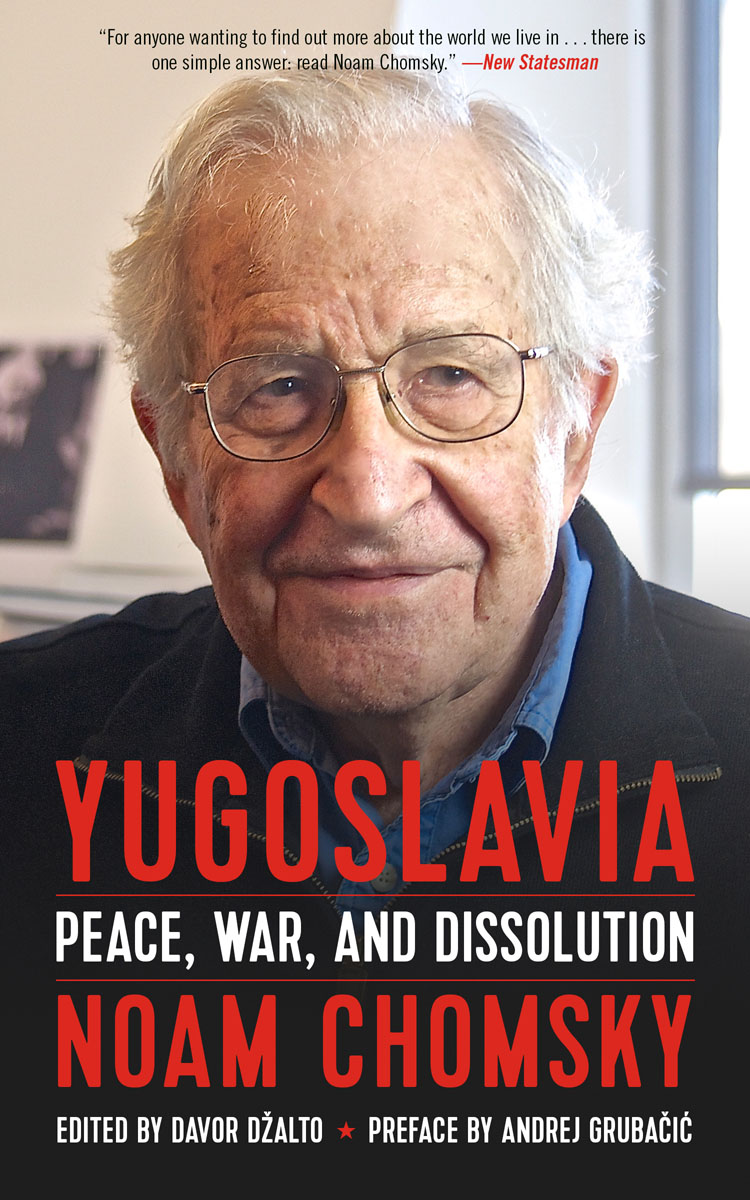

Yugoslavia: Peace, War, and Dissolution

Noam Chomsky. Edited by Davor Dalto

Valeria Chomsky 2018

Preface Andrej Grubai 2018

Introductory chapters Davor Dalto 2018

This edition 2018 PM Press

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 9781629634425

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017942916

Cover by John Yates / www.stealworks.com

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan.

www.thomsonshore.com

Contents

Andrej Grubai

Davor Dalto

Davor Dalto

Davor Dalto

Davor Dalto

Acknowledgments

This book would have never been completed without the enthusiasm, energy, and support that my dear colleague and friend Marina Sovilj invested in this project over a couple of years. I am deeply grateful for that.

I owe gratitude to my dear colleagues and friends Irene Caratelli, Borut Zidar, Vladimir Veljkovi, and Emil Dudevi. They gave me many important suggestions and comments that significantly improved the manuscript. My gratitude also extends to Milenko Srekovi, who provided me with important materials for documenting and understanding some of the recent developments in the region.

I am grateful to my assistant Ella May Sumner; I cannot imagine the completion of this project without all the time and effort she invested in addressing many practical aspects of the process.

A big thank you also goes to Anthony Arnove, who continued to support this project over many years.

Last but certainly not least, I want to thank Noam Chomsky, one of the greatest intellectuals and humanists of our time, for his tireless engagement in the worlds affairs and for his struggle against injustice, oppression, and imperial ambitions everywhere, not least in the Balkans.

Ed.

Remaining Yugoslav

Andrej Grubai

Sixty years ago, the concrete pier that butts against the Adriatic in the village of Trpanj was strewn with drying fishing nets. Local fishers came into the cannery to empty their bursting nets, and in the summer tourists from the USSR mingled among them. Twenty years ago, it was empty, abandoned because of the Yugoslav civil war. Stone buildings that had housed gathering places and families were transformed into hospitals, the fishing boats long abandoned. I look upon the same pier today, busy with young families and tourists, mostly from the former Soviet republics. A short walk from the harbor, I come upon a magazine stall. The papers report on the most recent attempt to change the name of Marshal Tito Square, five hours north in Zagreb, the capital of Croatia. Despite the passing of decades, the battle for the soul of Croatia, now a member of the European Union, and all of former Yugoslavia rages on. Was Comrade Tito a good Croatian or a pro-Serb dictator? Who inherits modern-day Croatia, antifascists or the heirs of the Ustae, infamous Nazi-collaborators?

Few in the U.S. have tackled the complexity of the former Yugoslavia the way that Noam Chomsky has. When asked to write this preface, I started reworking my way through Noams writing. His analysis is ruthless, clinical. His debates with the Guardians George Monbiot and the new intellectuals of the Bosnian Institute of England are the stuff of legend. Noams influence on public discourse in the countries of former Yugoslavia remains unparalleled. As I read through his writings, I was struck by what I consider an Alexievich moment, an absence of what Russian oral historian Svetlana Alexievich called the interior life of socialism, or socialism of the soul. (Only a Russian could come up with such a delightful phrase!) Alexievich was referring to everyday life under socialism, a challenge to an oft-repeated falsehood of capitalist historians: that all the worlds socialisms were alike. Of course those of us who grew up in the formerly socialist worldineptly referred to as Eastern Europe, or where the boogeyman lives, as a friend from Ohio once told me, only half jokinghave certain things in common. But the Soviet man and the Yugoslav woman, for example, were quite different. And they had little in common with a Bulgarian or Romanian socialist citizen.

This preface aspires to be one glimpse of the interior life of former Yugoslavia from the perspective of a Yugoslav, of a Yugoslav exile. And even after multiple exilesfirst from Yugoslavia at the end of socialism and later from what was left of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia after the 1999 NATO bombingsI remain a Yugoslav. My family has lived at the same Belgrade address, first in Socialist Yugoslavia, then the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Serbia and Montenegro, and today, Serbia. My story and that of my family are at the same time idiosyncratic and representative of Yugoslav history.

I never met Comrade Tito. But I remember the day he died in May 1980. His funeral procession in Belgrade brought seven hundred thousand to the streets, millions of people wept and mourned throughout Yugoslavia. Many of them were Tito loyalists, pledging their allegiance to our endangered socialist homeland. Many others, like myself, were proud to call themselves Yugoslavs, proud to be from a communist country. A country that hosted the Living Theatre, a country that was home to the music of Laibach and the Black Wave cinema of Duan Makavejev.

Even as a child, I knew our Yugoslavia was an anomaly. We played Partisans and Germans, not Cowboys and Indians. In the U.S., children cross their hearts and hope to die when they make a promise or swear theyre telling the truth. As school children in Yugoslavia, we would say Tita mi!I swear on Comrade Tito! For us, there was nothing more sacred. The adults were equally serious. When I was seven, my teacher asked whom I loved more, my mother or Comrade Tito. When I chose my motherafter all, I reasoned, I had never met Tito, while Id gotten to know my mother quite wellI was called a reactionary and sent home in tears. My mother was fuming; she marched straight to the school, and I was allowed to return the next day.

But my mother could afford to do things like that: her father Rato was one of the most celebrated communists in Yugoslavia. His first family, he once told my mother, was the Communist Party: he was the last secretary of the legendary Communist Youth; a minister in the first postWorld War II Yugoslav state; a member of the Central Committee of the League of Yugoslav Communists; an ambassador to the Non-Aligned Movement; the president of the Socialist Federal Republic of Bosnia; later becoming a member of the rotating Yugoslav presidency after Titos death. Even before World War II, my grandfather was well known: a professional football player (real football, not that odd thing people do in the U.S.). He used trips to away games to distribute party material. It is even said that he and his cousin Miljenko Cvitkovi, a fighter in the Spanish Revolution, attempted to assassinate the anti-communist Minister of the Interior of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Luckily for the minister (and for my grandfather), they did not find him.

Next page