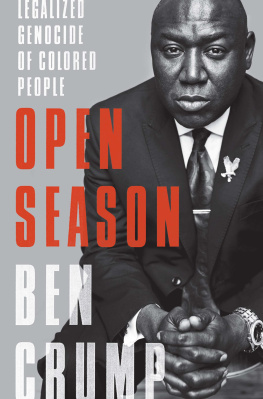

Ben Crump - Open Season

Here you can read online Ben Crump - Open Season full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Amistad, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Open Season: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Open Season" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Open Season — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Open Season" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Chancellor, Darious, Jamarcus, Brooklyn, and Genae

I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change.

I am changing the things I cannot accept.

Angela Davis

M y journey to fight for justice started back when I was just a child. In the fall of 1978, in my hometown of Lumberton, North Carolina, for the first time Black kids from the Southside were being educated alongside white kids. As a result, nine- and ten-year-old Black children began playing and forming friendships together with their white peers, because thats what kids do when left to their own inclinations.

Lunchtime, however, generated something more familiar and less welcomeseparation. I stood with all the other Black kids in a long line in the cafeteria, clutching my lunch card. This was the line for free lunches, a benefit that was based on our parents relatively low incomes. All of the kidsBlack and whitehad been divided into three categories: free lunch, reduced-price lunch, or what was called la carte. The la carte lunch cost a full two dollars, and it offered many delicious options: hamburgers, fries, pizza, soda, milkshakes, pretzels, potato chips, and more.

That day, as we stood at the back of the long free-lunch line, a white girl named Jenny came over, accompanied by a Black girl named Kina Ann, who was one of my neighbors in a government housing complex. I and the other Black students were complaining about how slowly the line was moving and how hungry we were, when Jenny pulled out a hundred-dollar bill. She said that she and Kina Ann were going to get cheeseburgers and fries.

We looked at the money in astonishment. A hundred-dollar bill! She was in the fourth grade! My friend Kevin asked her where shed gotten it and why she had it. Jenny said it was her weekly allowance from her parents. We Black kids looked at each other in astonishment. We didnt believe her, and we told her so. To prove to us that it was her money and she could do anything that she wanted with it, Jenny led us to the la carte line and bought lunch for all of us.

I thought about what happened the whole way home on the school bus. Gazing out of the window, I noticed signs emblazoned with Jennys family name on the funeral home, the nursing home, and several pharmacies along the highway. I was stunned that a ten-year-old girl had an allowance that was the equivalent of my mothers weekly income working two jobsone in a hotel laundry room during the day and another at the Converse shoe factory at night.

I wanted to understand why people on the white side of the tracks had it so good and Black people on our side of the tracks had it so bad. I wanted to understand this money and ownership disparity that seemed to be very much tied up with economic justice and raceand this began my journey toward becoming a lawyer and a crusader for racial, social, and economic justice. During this period, when the Black fourth-graders of South Lumberton were bused across the train tracks to L. Gilbert Carroll Middle School, nestled in the white section of town, my mother explained that we finally had achieved school integration. Now, she said, we could attend the best schools our city had to offer and gain access to new books and knowledge.

I was grateful for the better educational resources, and I soon learned that this was the work of a lawyer named Thurgood Marshall in a series of legal cases that came to be known as Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka. Thurgood Marshall, a devoted and gifted attorney, and his associates had fought and triumphed in an uphill battle to end the legal basis for segregating schools and other public facilities. My path was carved and my goal came into view: I would become an attorney like Thurgood Marshall, and I would fight to make life better for the people from my side of the tracks. I would fight for equal opportunity for the most marginalized and disenfranchised to attain what many still call the American Dream. I was going to fight for all people to have an equal chance at justice and an equal chance at freedom.

However, after many years of practicing law on the front lines of the justice system, I learned that it is dangerous to be a colored person in America. By colored person, I mean Black and brown people and people who are colored by their sexual preference, religious beliefs, or gender. In short, I define a person of color as anyone who is a nonwhite male. I will show what I have learned as a civil rights attorneythat the justice system has been designed to protect white, wealthy men, and the rest of us are on our own.

Although Open Season is primarily about the continuing struggle for justice for all, it is also my case for what happens when a segment of the population is consistently denied access to fair treatment under the law and in almost every other aspect of their lives. It discusses the racism and oppression still visibly prevalent in the United States, particularly when it comes to law enforcement, the legal system, and the very foundation of our nation. This book, featuring many of the cases I have worked on, reveals the systematic legalization of discrimination in the United States and particularly how it can lead to genocidethe intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a people. This book particularly addresses genocide as it relates to colored people.

Most of the population may find my claim boldthat the legal system and nearly every other institution formed in the United States is out to eliminate Black and brown people, but most colored folks certainly believe it is true.

Korey Wise, one of the kids labeled the Central Park Five (now becoming known as the Exonerated Five), said that when he was initially brought into the police station for questioning about the rape of a white woman, he felt that a force way larger than himself was orchestrating the interrogationsomething with a lot of momentum, something powerful, something big. He said it wasnt until during a private screening of Ava DuVernays documentary When They See Us that he realized what this monster was that was after him. It was the prosecutors, the police, the media, and the city of New York.

And its not just youth trapped in police stations who feel this force, who feel hunted. Wealthy Blacks with good reason feel under constant threat that society is out to get them too. They are well aware of the Greenwood Massacre, in which a prosperous Black section of Tulsa, Oklahoma, known as Black Wall Street, was burned to the ground by white people in 1921. Nearly three hundred Blacks were killed.

Although I primarily use contemporary cases to make the point concerning genocide, it has been an issue since Africans were kidnapped and auctioned off in the United States during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This is wholesale removal, but a much more comprehensive and efficacious form of genocide occurs when a people is systematically stripped of essential physical and emotional supports necessary for their well-being in a subtle, insidious, and almost invisible manner. I will explain how this systematic subtle genocide occurs legally and how it is killing people of color slowly and ever so softly by cutting into the soul of their humanity. It is being done one cut at a time, to one person at a time, so as not to cause any alarm. It is easy to kill one person a day with a bullet or a lengthy prison sentence and justify it legally; it is much more difficult to justify killing many people at once in dramatic fashion. But the effect is the same. The act of genocide occurs when the laws of this country and their enforcement and adjudication are used to cut into the heart and soul of colored people.

In other words, there are many ways to kill a race of people. You can take away their hope for a better life. You can deny them access to quality food and health care. You can flood their community with drugs. You can take away safe, decent housing. You can lock them up for crimes they did not commit. In short, you can kill their spirit so they become the walking dead.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Open Season»

Look at similar books to Open Season. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Open Season and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.