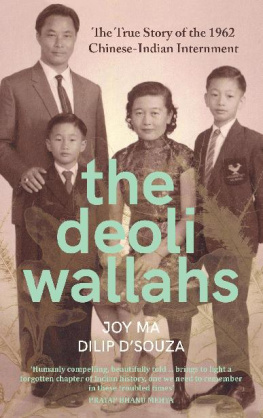

I dedicate this book to my parents Jack and Effa and my brothers Lynden and William. They instilled in me through their quiet strength that our familys experience and the stories of others who suffered internment should be told.

Joy Ma

This book is for people in the Chinese-Indian community above all, who opened their hearts and minds to me, and opened my eyes. In Assam, Calcutta, Toronto, California. No names because the 1962 fear lives on among so many, but you know who you are. Thank you.

This book is also dedicated to the memory of my in-laws, Sadhana and Narendra Kamat, whose unwavering integrity and sense of justice opened my eyes too.

Dilip DSouza

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The Strange Story of an Incarceration

I n the bus on the way back, the group asked seventy-something Ying Sheng Wong to sing. Looking at him, looking around at the others in the bus, I assumed idly that he would break into a Chinese song. After all, these folks looked Chinese.

Then Ying Sheng sang, and he sang Ajeeb Dastan Hai Yeh (This is a strange story), the lyrical song from the 1960 Bollywood hit film Dil Apna Aur Preet Parai (My Heart is Mine but My Love Belongs to Someone Else). It nearly brought tears to my eyes for two reasons. One, here was this Chinese-Indian man who left India several decades ago, sitting in a bus speeding along of all places the highway from Ottawa to Toronto, singing this old Hindi song. Charming, but the knot in my gut told me how inexpressibly sad this scene it was. Two, to my chagrin, I realized that my assumption about their looks was the same one that once sent Wong and a few thousand others to a detention camp in Rajasthan. Truly, their only fault then was that they looked Chinese.

Early on the morning of 24 August 2017, Ying Sheng and fifty other Chinese-Indians had gathered in the parking lot of the Splendid China Mall in Toronto. They had planned something rather remarkable for the day: an expedition by bus to the Indian High Commission in Ottawa, where they intended to hold a peaceful demonstration and hand over a letter addressed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, asking for an apology. This tiny community had finally drummed up the wherewithal to speak out and ask for some measure of redress for what had once happened to them fifty-five years ago.

For what had happened to them was unjust indeed.

In 1962, India and China fought a war over their border. In India, people of Chinese ancestry Chinese-Indians were immediately viewed with suspicion. It might have remained at that, but the suspicions turned instead into official policy, and starting in November 1962, the Indian government incarcerated nearly 3,000 Chinese-Indians in a prison camp in Deoli, Rajasthan. These were people, in many cases, whose families had lived in India for generations, who spoke only Indian languages, who had no connection to China. Their sudden incarceration left them bewildered and disillusioned with India.

Why this happened and why so few Indians know about this episode are questions this book will explore.

The parallel, of course, is the American incarceration of 100,000 Japanese-Americans in prison camps, two decades earlier. The reason ran in parallel as well war World War II in 1942; the IndiaChina border war in November 1962. The respective conflicts spurred the worlds two largest democracies to suspect the loyalties of thousands of their own citizens, solely because they looked the way they did a suspicion that soon led to their incarceration.

Like the Japanese in the US, the Chinese have had a long history in India. Starting in the late eighteenth century, they came over as traders, tea-plantation workers, cobblers, dentists and other professionals, settling mostly in small towns across Indias Northeast. As the generations slipped past, several families became Indian enough that they spoke only local languages. They were so much a part of the local fabric that in some of these towns, you can still find reminders of their presence. Like Hong Kong Restaurant in Tinsukia, Assam, started by a man who did his time in the Camp it is in Chinapatty, Makum Road. (The best translation of Chinapatty might be Chinese hood or even Chinatown.) Makum, the small town seven kilometres east of Tinsukia along that road, has a neighbourhood also called Chinapatty, bounded by what is still called Chinapatty Road and the Makum railway station. Back in 1962, given the people who lived there, these names must have made demographic and geographic sense, unlike today, when there are so few ethnic Chinese in these towns.

If I could turn the clock back, I would try to get a sense of the mood in these neighbourhoods in late 1962, when war broke out with China. For with the war, Indias President S. Radhakrishnan signed the Defence of India Act, allowing authorities to arrest people suspected of being of hostile origin. Across Northeast India, and despite the years of familiarity, this is just what plenty of angry Indians had begun thinking anyway that their neighbours from Chinapatty who looked Chinese were of hostile origin. The police machinery then swung into action, knocking on Chinese-Indian doors in Darjeeling and Kalimpong, Tinsukia and Makum, and elsewhere, giving bewildered families short warning to pack a few essentials and report to the police station. Sometimes, they simply took away the head of the family. Often, it was the men. It must have seemed disconcertingly random. Eventually, all these prisoners were bundled onto a train that actually started from the Makum railway station that marked out Chinapatty, and it trundled west across the country for a week. Along the way, wherever the train halted for food or fuel, fellow Indians threw stones and screamed at the hapless captives, Go back, Chinese! When the journey finally came to an end, they were in a dusty town on the edge of the desert in Rajasthan Deoli. They were hustled into an old British camp there among other things, it had been used for German and Japanese prisoners of war during World War II and were given numbers, identity cards and assigned to barracks.

Many Chinese-Indians spent up to five years in Deoli Camp. Some died there. Some were deported to China on ships a strange and cruel fate to visit on people whose families had been Indian for generations, who spoke only Indian languages and for whom China was a country as foreign as, say, Rwanda might have been. Others who made their way home after the internment were reduced to poverty, lacking even the taxi fare home from the train station, their property stolen or vandalized. Effa Ma, for example, was pregnant when she went to the Camp. She gave birth there. Years later, the family was released and sent to Calcutta. In a recent short film, she recalls her return to Calcutta: It was July the 1st. It was raining ... Where [could] I go with these three kids and not a pie in my pocket? ... I had nobody to come to receive me!

From these dire straits, the community had to rebuild. Some people managed as best they could, running restaurants and beauty parlours that did moderately well. But it was hard work winning back even a degree of acceptance from the neighbours. Over the years, many chose to leave the country that had so profoundly betrayed them, emigrating to Canada, the US and elsewhere. In particular, Toronto has a substantial community of these migrs and their families. They meet regularly, go on picnics and have even formed the Association of India Deoli Camp Internees (AIDCI).

Social gatherings are fine, but the AIDCI knows theres an elephant in the room.