Who built Thebes of the seven gates?

In the books you will find the names of kings.

Did the kings haul up the lumps of rock?

And Babylon, many times demolished

Who raised it up so many times? In what houses

Of gold-glittering Lima did the builders live?

Where, the evening that the Wall of China was finished

Did the masons go? Great Rome

Is full of triumphal arches. Who erected them? Over whom

Did the Caesars triumph? Had Byzantium, much praised in song

Only palaces for its inhabitants? Even in fabled Atlantis

The night the ocean engulfed it

The drowning still bawled for their slaves.

The young Alexander conquered India.

Was he alone?

Caesar beat the Gauls.

Did he not have even a cook with him?

Philip of Spain wept when his armada

Went down. Was he the only one to weep?

Frederick the Second won the Seven Years War. Who

Else won it?

Every page a victory.

Who cooked the feast for the victors?

Every ten years a great man.

Who paid the bill?

So many reports.

So many questions.

Questions from a Worker who Reads by Bertolt Brecht

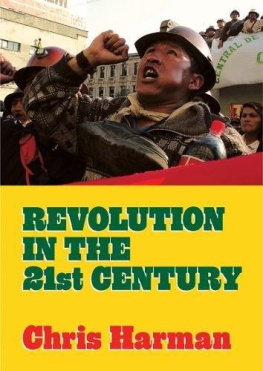

The questions raised in Brechts poem are crying out for answers. Providing them should be the task of history. It should not be regarded as the preserve of a small group of specialists, or a luxury for those who can afford it. History is not bunk, as claimed by Henry Ford, pioneer of mass motor car production, bitter enemy of trade unionism and early admirer of Adolf Hitler.

History is about the sequence of events that led to the lives we lead today. It is the story of how we came to be ourselves. Understanding it is the key to finding out if and how we can further change the world in which we live. He who controls the past controls the future is one of the slogans of the totalitarians who control the state in George Orwells novel 1984 . It is a slogan always taken seriously by those living in the palaces and eating the banquets described in Brechts Questions.

Some 22 centuries ago a Chinese emperor decreed the death penalty for those who used the past to criticise the present. The Aztecs attempted to destroy records of previous states when they conquered the Valley of Mexico in the fifteenth century, and the Spanish attempted to destroy all Aztec records when they in turn conquered the region in the 1620s.

Things have not been all that different in the last century. Challenging the official historians of Stalin or Hitler meant prison, exile or death. Only 30 years ago Spanish historians were not allowed to delve into the bombing of the Basque city of Guernica, or Hungarian historians to investigate the events of 1956. More recently, friends of mine in Greece faced trial for challenging the states version of how it annexed much of Macedonia before the First World War.

Overt state repression may seem relatively unusual in Western industrial countries. But subtler methods of control are ever present. As I write, a New Labour government is insisting schools must stress British history and British achievements, and that pupils must learn the name and dates of great Britons. In higher education, the historians most in accord with establishment opinions are still the ones who receive honours, while those who challenge such opinions are kept out of key university positions. Compromise, compromise remains the way for you to rise.

Since the time of the first pharaohs (5,000 years ago) rulers have presented history as being a list of achievements by themselves and their forebears. Such Great Men are supposed to have built cities and monuments, to have brought prosperity, to have been responsible for great works or military victories and, conversely, Evil Men are supposed to be responsible for everything bad in the world. The first works of history were lists of monarchs and dynasties known as King Lists. Learning similar lists remained a major part of history as taught in the schools of Britain 40 years ago. New Labour and the Tory opposition seem intent on reimposing it.

For this version of history, knowledge consists simply in being able to memorise such lists, in the fashion of the Memory Man or the Mastermind contestant. It is a Trivial Pursuits version of history that provides no help in understanding either the past or the present.

There is another way of looking at history, in conscious opposition to the Great Man approach. It takes particular events and tells their story, sometimes from the point of view of the ordinary participants. This can fascinate people. There are large audiences for television programmes even whole channels which make use of such material. School students presented with it show an interest rare with the old kings, dates and events method.

But such history from below can miss out something of great importance, the interconnection of events.

Simply empathising with the people involved in one event cannot, by itself, bring you to understand the wider forces that shaped their lives, and still shape ours. You cannot, for instance, understand the rise of Christianity without understanding the rise and fall of the Roman Empire. You cannot understand the flowering of art during the Renaissance without understanding the great crises of European feudalism and the advance of civilisation on continents outside Europe. You cannot understand the workers movements of the nineteenth century without understanding the industrial revolution. And you cannot begin to grasp how humanity arrived at its present condition without understanding the interrelation of these and many other events.

The aim of this book is to try to provide such an overview.

I do not pretend to provide a complete account of human history. Missing are many personages and many events which are essential to a detailed history of any period. But you do not need to know about every detail of humanitys past to understand the general pattern that has led to the present.

It was Karl Marx who provided an insight into this general pattern. He pointed out that human beings have only been able to survive on this planet through cooperative effort to make a livelihood, and that every new way of making such a livelihood has necessitated changes in their wider relationships with each other. Changes in what he called the forces of production are associated with changes in the relations of production, and these eventually transform the wider relationships in society as a whole.