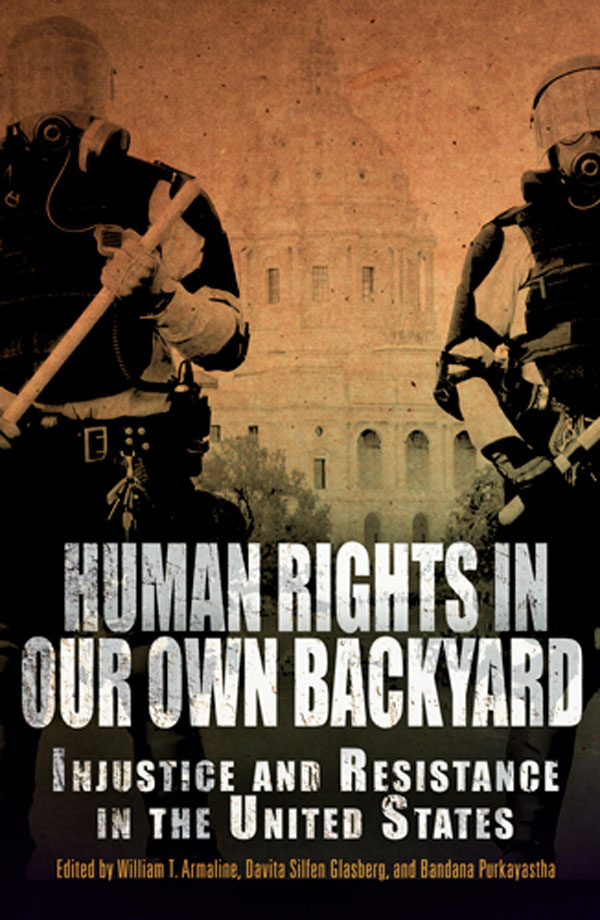

HUMAN RIGHTS IN OUR

OWN BACKYARD

PENNSYLVANIA STUDIES IN HUMAN RIGHTS

Bert B. Lockwood, Jr., Series Editor

A complete list of books in the series

is available from the publisher.

HUMAN RIGHTS

IN OUR OWN

BACKYARD

Injustice and Resistance in the United States

Edited by

William T. Armaline,

Davita Silfen Glasberg,

and Bandana Purkayastha

Copyright 2011 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Human Rights in our own backyard: injustice and resistance in the United States / edited by William T. Armaline, Davita Silfen Glasberg, and Bandana Purkayastha.1st ed.

p. cm. (Pennsylvania studies in human rights)

ISBN 978-0-8122-4360-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Human rightsUnited States. 2. Human rightsGovernment policyUnited States. I. Armaline, William T. II. Glasberg, Davita Silfen. III. Purkayastha, Bandana, 1956. IV. Series

JC599.U6 H85 2011 |

323.0973 | 2011024455 |

CONTENTS

Julie Elkins and Shareen Hertel

Andrew S. Fullerton and Dwanna L. Robertson

Davita Silfen Glasberg, Angie Beeman, and Colleen Casey

Deric Shannon

Amanda Ploch

Barret Katuna

Abraham P. DeLeon

Barbara Gurr

Miho Iwata and Bandana Purkayastha

Christine Zozula

Bill Frelick

Sang Hea Kil, Jennifer Allen, and Zoe Hammer

Katie Acosta

Shweta Majumdar Adur

Bandana Purkayastha, Aheli Purkayastha, and Chandra Waring

William T. Armaline

Tola Olu Pearce

Ranita Ray

Stacy A. Missari

Chivy Sok and Kenneth J. Neubeck

Zoe Hammer

William T. Armaline, Davita Silfen Glasberg, and Bandana Purkayastha

FOREWORD

Judith Blau

Dictionaries define enterprise as adventure, undertaking, resourceful, energy, pluck, boldness, and audacity. It is in this spirit that the editors and authors of Human Rights In Our Own Backyard propose to advance our deep understanding of human rights. Even betterthey also advance the sort of understanding that will encourage their readers to take actionto lobby, organize, and redirect the path of our communities and the nation. One of the strengths of this reader is that the editors and authors have subsumed the stalwarts of sociologysocial problems, racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, xenophobia, and class dominanceunder the more generic term, human rights. This is a stunning achievement. It clarifies how parsimonious human rights principlesnotably equality, self-determination, and human dignitycan help us to organize our thinking, collaborate with others, and take action. Human rights principles are so simple a five-year-old can intuitively understand them, while they befuddle most adults. This wonderful book helps to clarify human rights for us.

None would say that human rights are simple, but the international human rights community has emphasized their universality. They apply as much to the peoples living in the United States as they apply to the peoples of Papua New Guinea. The problem is that Americans have become obsessed with human rights violations elsewhere and fail to recognize the human rights violations in our own country (that is, in our own backyard). I would like to address a few preliminary questions, most of which are touched on by chapter authors but which merit emphasizing.

First, since human rights laws, treaties, and constitutional issues lie within the domain of the legal profession, why are we social scientists qualified to engage this enterprise? Second, why have human rights made such a dramatic appearance in the American academy in the past few years? A related question is why has human rights become a global movement and why has the movement accelerated during the past decade? Third, if human rights are universal, why do we say that they are multilayered, embedded, and contingent? Fourth, why is it important to be self-critical as Americans? And finally, I would like to briefly discuss what I believe is one of the greatest obstacles to the realization of human rights in America, and that is the tenacious hold that corporations have on communities.

Lets take them in that order. First, what distinctive qualifications do social scientists bring to the table to analyze and advance human rights? As this reader makes clear, human rights are embedded in neighborhoods, communities, culture, communication, and society. None are better trained in studying and understanding these dimensions than social scientists. Yes, of course, many human rights must be codified, making the distinctive skills of lawyers important, but we are increasingly aware that human rights are relational and depend on processes that are embedded in institutions, communities, and depend not only on peoples relations with one another, but their relations to the land, natural resources, and the environment, and yes, the arts and sports. There is room for everyone under the human rights tent. But, let me be clear: it will not be easy since people of privilege and wealthy corporations want to have no part in sharing their human rights with others. Discrimination advantages those who discriminate, and extending food rights to the poor is not in the interest of corporations and banks. Except of course, as the saying goes, what comes around goes around. Therefore, we try to be ethical.

Second, why are human rights catching hold in the American academy? To address that question we need to initially ask why human rights have become a global movement, especially during the past decade. After all, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was approved by the United Nations General Assembly over sixty years ago, in 1948. These questions are complicated, but I will be brief. The consensus is that new communications technologies fueled economic globalization that in turn created immense economic inequalities, ecological disasters, and population displacement (e.g., Kurasawa 2007). Yet the same communications technology that drove economic globalization also opened up opportunities for global civil society, which is to say, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as the World Social Forum, La Campesina, Shackpeople International, Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions, Center for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and, quite literally, many thousands of others. These NGOs, often affiliated with the United Nations, are dedicated to advancing human rights, locally, nationally, and internationally.

But why have human rights made such a dramatic appearance in the American academy in the last few years? As mentioned above, rapid and intensive economic globalization has had an adverse impact on communities and sometimes on the peoples of entire countries, such as Nigeria, where foreign oil companies ruined the environment and caused intense intergroup rivalries, Bolivia, which contended with the privatization of water by Bechtel Corporation, and many poor countries in which the United States dumped subsidized agricultural products, driving peasant-farmers off their lands.