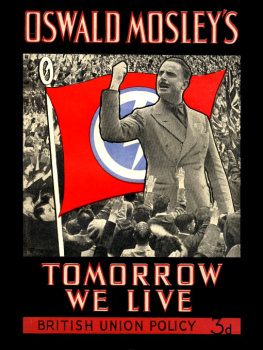

B. U. F.

B. U. F.

Oswald Mosley and British Fascism

B Y

J A M E S D R E N N A N

Antelope Hill Publishing

The content of this work is in the public domain.

Slight alterations have been made to the text for readability suited to the modern reader, and annotations have been added.

Originally published in 1934, London.

Republished 2020 by Antelope Hill Publishing.

Printed in the United States of America.

Cover art by sswifty.

The publisher can be contacted at

Antelopehillpublishing.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-953730-21-3

To

C. M.

WHO WANTED THIS BOOK WRITTEN

Contents

Quotations

We still hold the same purpose; we still proclaim the same vow. Before we leave the mortal scene we will do something to lift the burdens of those who suffer. Before we go we will do something great for England. Through and beyond the failures of men and parties, we of the war generation are marching on, and we shall march on until our end is achieved and our sacrifice atoned. To-day we march with a calm but mighty confidence, for marching beside us in irresistible power is the soul of England.

OSWALD MOSLEY

Mosley has been here. A man of courage and intelligence.

MUSSOLINI

Sir Oswald Mosleya very interesting man to read just now: one of the few people who are writing and thinking about real things, and not about figments and phrases. You will hear something more of Sir Oswald Mosley before you are through with him. I know you dislike him, because he looks like a man who has some physical courage and is going to do something; and that is a terrible thing. You instinctively hate him, because you do not know where he will land you; and he evidently means to uproot some of you. Instead of talking round and round political subjects and obscuring them with bunk verbiage without ever touching them, and without understanding them, all the time assuming states of things which ceased to exist from twenty to six hundred and fifty years ago, he keeps hard down on the actual facts of the situation. When you pose him with the American question: Whats the big idea? he replies at once: Fascism; for he sees that Fascism is a big idea, and that it is the only visible practical alternative to Communismif it really is an alternative and not a half-way house. The moment things begin seriously to break up and something has to be done, quite a number of men like Mosley will come to the front who are at present ridiculed as Impossibles. Let me remind you that Mussolini began as a man with about twenty-five votes. It did not take him very many years to become the Dictator of Italy. I do not say that Sir Oswald Mosley is going to become the Dictator of this country, though more improbable things have happened.

BERNARD SHAWIn Praise of Guy Fawkes

Introduction

A study of Oswald Mosley needs no apology. Those who dislike his personalitythey are not few, those who disparage his abilitiesthey are fewer, and those who fear his policiesthey are many, have either to admit that he is the most startling, the most objectionable, or the most stimulating among the men who have created or disturbed the politics of post-war Britain.

At thirty-seven, Oswald Mosley is already an experienced parliamentarian. None of his generation, and not many of his contemporaries, can claim the same continuity of experience throughout the history of the two post-war decades. His changes of political allegiance which have aroused the hostility of the older parties seem rather to represent the unsatisfied search for a valid creed by which so many other men of his years have in their own minds been troubled. During the Coalition Parliament, Mosley first emerged as the associate of Lord Robert Cecil, Colonel Aubrey Herbert and Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, in a forlorn effort to represent something of a new Tory ideal in that ill-assorted and heterogeneous assembly. Again, with others of his generation, he suffered disillusion in the ranks of the Labour Party, and emergedat the sacrifice of an orthodox political careerto attempt a leadership of his own. As an orator even his most caustic critics will admit that he is outstanding. As an administrator he proved his abilities in a field where his opportunities were restricted both by circumstances and by colleagues. His failures as a tactician in politics may yet prove to have laid the basis of his success in the strategy of statesmanship.

But it is not as a younger parliamentarian that Oswald Mosley attracts the interest of his fellows, and arouses the fury or enthusiasm of the crowd. A great glamour has gathered round his figureso strange, so provocative, in the dun ranks of English politicians. He is very Englishas it were, a composite ghost of English historyyet his enemies complain that he is so un-English. Perhaps they mean that he lacks that bourgeois stamp which has moulded to its flaccid type the generations of English politicians who have grown up since the Industrial Revolution. There is something of the Elizabethan in his gallant, rather arrogant, air. He is the Englishman of the Carolean tennis-court; of the dueling-ground rather than of the Pall Mall Club. Then again, with his wrestling, boxing and fencing, he has walked in the tradition of the Regency buck, in a time when people have got into the habit of expecting younger politicians to have horn-rimmed spectacles and soft, white hands, and to spend their holidays at Geneva.

He is a big man of blood and bone, of strong tones, no feeble creature of grey shadings. He is a personality, with all his individual qualities and faults, no self-complacent bladder of conventions. It is, of course, important in a leader, this question of distinctive personality, and it is no doubt a symptom of the determinism of history that each period, each new phase, throws up its peculiar individuals, who respond in an observable degree to contemporary currents of opinion, taste and underlying aspirations. The suave and placid Walpole; the morose, dynamic Pitt; his pedantic, determined son; the cynical, ineffectual Fox, were each in their day the expression of passing moods and attitudes to life in the governing class. So, in the nineteenth century, Disraeli, the supreme type of the company promoter, showed the way to Empire, and Gladstone stood for millions of whiskered, frockcoated Dissenting investors, who took their profits, disapproved, and explained to their white consciences the intrinsic v irtue of all profit. Again, in the postwar period, when the British middle class contemplates the incredible fact that the capitalist system is fallible and passing, and that all the standards of the Victorian age are crumbling into the abyss, they produce the cautious Stanley Baldwin, with his limpet philosophy, his refusal to believe the unbelievable, his pipe-poor symbol of a lost tranquility. He would be pathetic, were his pathos not so dangerous; and MacDonald, too, the quack doctor of the boarding-house advertisement readers, who assuages alarm by his confession that, after all, the family practitioner was right.

Mosley is of another world to theseof the world that is coming into being. An omen and a portent to some; to the majority, according to their opinion, a class-traitor and a revolutionary, or an unscrupulous adventurer, who might have done great things in one party or the other.

Mosley is, at the least, an interesting phenomenon in modern English politics; and in his greatest potentiality he stands for new and revolutionary conceptions in politics, in economics, and in life itself. He may emerge with his young men from the small faction-fights in the mean halls of mean streets to the leadership of modern England. Or he may fail and be forgotten more than Dilke, and pitied less than Randolph Churchill. If England slips into another long Walpolean lassitude, as it did after the Marlborough wars, and if some form of continuing National Governmenta revivified Whigdomproves to be the measured expression of the English mind through a period of quiescence or decay, then Mosley will have achieved the greatest personal tragedy in English history since Bolingbroke.

Next page