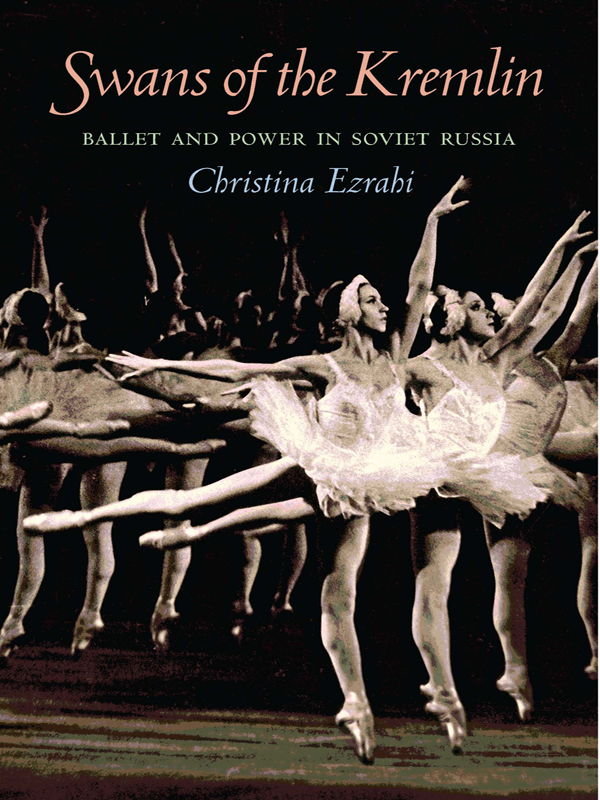

Christina Ezrahi - Swans of the Kremlin

Here you can read online Christina Ezrahi - Swans of the Kremlin full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: University of Pittsburgh Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Swans of the Kremlin

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Pittsburgh Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Swans of the Kremlin: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Swans of the Kremlin" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Swans of the Kremlin — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Swans of the Kremlin" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PITT SERIES IN RUSSIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES

Jonathan Harris, Editor

Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260

Copyright 2012, University of Pittsburgh Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published in Great Britain in 2012 by Dance Books Ltd., Southwold House, Isington Road, Binsted, Hampshire. GU34 4 PH

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ezrahi, Christina.

Swans of the Kremlin : ballet and power in Soviet Russia / Christina Ezrahi.

p. cm. (Pitt russian east european)

ISBN 978-0-8229-6214-4 (pbk.)

1. BalletSoviet UnionHistory. 2. DanceSoviet UnionHistory. 3. DancePolitical aspectsSoviet Union. I. Title.

GV1663.E97 2012

792.80947dc23 2012030694

CIP catalog record is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-85-273158-8

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-7807-7 (electronic)

To Ariel, Lina, and Yariv

The sublime dancers of the Mariinsky-Kirov and the Bolshoi, who elevated the art of ballet throughout the tumultuous twentieth century, inspired this research. I would like to thank the staff at the Central State Archive of Literature and the Arts in St. Petersburg and of the Russian State Archive of Literature and the Arts in Moscow. Ballet is a visual art, and this book would not have been the same without the help of Natalia Metelitsa, Tatiana Vlasova, and Sergei Laletin from the St. Petersburg State Museum of Theater and Music, Elena Lollo, Alisa Meves, Elena Mochalova, and Olga Ovechkina from the Mariinsky Theater, and of Gwyneth Campling and Victoria Relph from the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, who helped me obtain photographs for this book. I am grateful to the dancers of the Kirov and Bolshoi Ballet companies who have shared their thoughts with me over the years, above all Makharbek Vaziev, Olga Chenchikova, and Evgeny Goremykin.

I thank my editor, Peter Kracht, for his guidance and his enthusiasm about this project, which began at University College London's School of Slavonic and East European Studies. I am indebted to Alena Ledeneva and Geoffrey Hosking for their inspiring guidance and to Nancy Condee for her support. I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council and University College London for funding my work.

I am deeply grateful to my mother for sharing my love for Russian ballet and to my father for putting up with our enthusiasm. I am obliged to my parents-in-law, especially Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi and Ruth HaCohen, for nurturing me intellectually and gastronomically, but notably to Yaron Ezrahi, who has provided invaluable guidance at different stages. Above all, I would like to thank my husband, Ariel, who has become an expert on Russian ballet, my daughter, Lina, whose first words included Mariinsky and Bolshoi, and my son, Yariv, who chivalrously accompanied me to St. Petersburg even before he was born.

In my transliteration from Russian to English, I have used a modified version of the Library of Congress (LOC) system in the text. I have made the following changes for the endings of names:

-ii in the LOC system becomes -y (Lunacharsky, not Lunacharskii)

-aia in the LOC system becomes -aya (Plisetskaya, not Plisetskaia)

For Russian names frequently used in English, I use the most common English transliteration instead of the LOC system (for example: Bolshoi Theater, not Bol'shoi Theater; Tchaikovsky, not Chaikovskii).

I have used strict LOC transliteration for Russian words other than names that appear in the text, in source notes, and in the bibliography.

Unless noted, all translations are my own.

There is no precise English equivalent to the Russian uchilishche. I translate the term as institute.

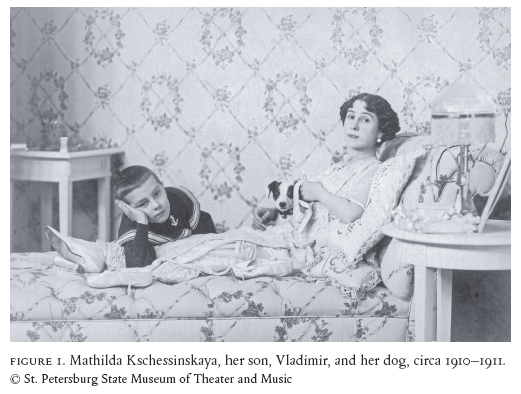

ON 26 FEBRUARY 1917, Mathilda Kschessinskaya received an urgent call from General Halle, the chief of police of the fashionable Petrograd district where she lived. Kschessinskaya was not only prima ballerina assoluta of the Mariinsky Ballet, but she was also the former mistress of Nicholas II and the current mistress of Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich, and Halle was anxious about her security. He warned Kschessinskaya that the situation in town was very serious and advised her to save whatever she could from her house before it was too late. The revolution had begun. The ballerina looked at the possessions decorating her elegant style moderne house and felt that her situation was desperate: her most important diamond pieces were kept at Faberg, but what was she to do with the incredible quantity of smaller items scattered around her house? When she sat down for dinner with her son, his tutor, and two dancers from the Mariinsky the following evening, shots could be heard next to her house. Kschessinskaya decided that it was time to leave. She put on her most modest fur coat, a black velvet coat trimmed with chinchilla, and threw a shawl over her head. Someone quickly lifted up her favorite fox terrier Dzhibi, whom she had almost forgotten, someone else carefully carried the traveling bag with her valuables, and they left. Kschessinskaya remained in Petrograd until July 1917, but she was not to live again in her house after that evening, finding shelter with friends and family instead. Driving past her former home, she once saw the most prominent female Bolshevik, the revolutionary Alexandra Kollontai, stroll around her garden in the ermine coat she had left behind:

The absurd image of Alexandra Kollontai taking a stroll in Kschessinskaya's ermine coat is emblematic of the paradoxical situation Russia's imperial ballet found itself in after the October Revolution. Ermine is the fur of kings, and Kschessinskaya's ermine coat symbolized the symbiotic relationship between Russia's imperial ballet and its patron, the tsarist regime. More than any other art form, ballet was a child of aristocratic court culture, yet it not only survived the upheaval of the early revolutionary period but soon claimed its place in the official pantheon of Soviet cultural achievements. Just as Kollontai had put Kschessinskaya's ermine coat around her shoulders, the Soviet regime adorned itself with ballet.

But could the Soviet regime ever claim full ownership, or control, over ballet? Could the artistry of the imperial ballet survive and develop after a revolution that destroyed the social and political order of which ballet had formed an intrinsic part, a revolution that held the utopian promise of a new world and demanded before long that art should become an engineer of human souls, a propaganda tool serving the ideological needs of the state?

Under the tsars, several theaters had received the title imperial, signifying their status as theaters operating under court supervision and on generous state funding. Russia's imperial ballet consisted of the ballet companies of two imperial theaters, the Mariinsky Theater of Opera and Balletin St. Petersburg and the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. Before the October Revolution, these two ensembles were the only public, state-supported ballet companies in Russia, even though from the late eighteenth century ballets were also performed by serf theaters maintained by aristocrats as part of Russia's flourishing private, aristocratic theatrical culture. In the last third of the nineteenth century, troupes of foreign ballet dancers began to perform in nongovernment-supported theaters springing up in the Russian provinces. After the ban on private companies in Moscow and St. Petersburg was lifted in the 1880s, touring companies also visited these two cities, especially in the summer. During the twilight years of imperial Russia, cabarets and theaters of miniatures emerged as centers for ballet experimentation. Strictly speaking, the Mariinsky and Bolshoi were thus not the only troupes performing in Russia, but as the only ballet companies with imperial status, they benefitted from the tsar's largesse and protection, enabling them to create those ballets at the heart of the classical canon that define our understanding of classical ballet to the present day. As this book is about the fate of Russia's imperial ballet after the revolution, it is therefore logical to focus on the former Mariinsky Ballet (known as Kirov Ballet for most of the Soviet period) and the Bolshoi Ballet and not on the numerous, but by comparison less significant, ballet ensembles created throughout the Soviet period.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Swans of the Kremlin»

Look at similar books to Swans of the Kremlin. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Swans of the Kremlin and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.