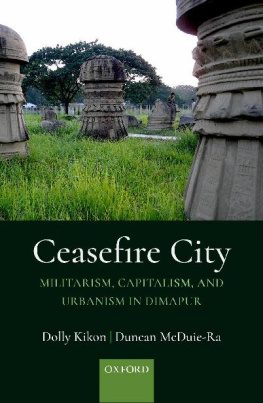

Ceasefire City

Ceasefire City

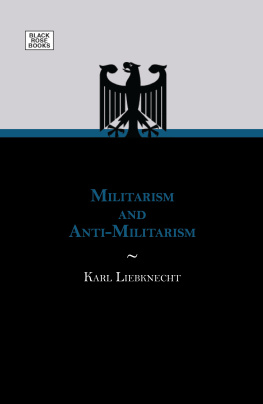

Militarism, Capitalism, and Urbanism in Dimapur

Dolly Kikon

Duncan McDuie-Ra

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trademark of

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in India by

Oxford University Press

22 Workspace, 2nd Floor, 1/22 Asaf Ali Road, New Delhi 110 002, India

Oxford University Press 2021

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

First Edition published in 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior

permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by

law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights

organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above

should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address

above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

ISBN-13 (print edition): 978-0-19-012973-6

ISBN-10 (print edition): 0-19-012973-5

ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-0-19-099267-5

ISBN-10 (eBook): 0-19-099267-0

Typeset in ScalaPro 10/13

by The Graphics Solution, New Delhi 110 092

Printed in India by Rakmo Press, New Delhi 110 020

Contents

Dimapur is no longer an obscure place. It is my good fortune that I witnessed a town turn into a city, but it is even more exciting that I wrote a book about this exceptional city. I want to thank my co-author Duncan McDuie-Ra for taking this adventurous journey with me to explore and wander through Dimapur. Thank you for your courage to dream with me and write this book together. Your friendship, commitment, and wisdom to collaborate and write about a city where desires, dreams, death, and danger surround its residents have profoundly shaped my understanding about frontier urbanism. I am deeply indebted to your intellectual generosity and fellowship.

I was born in Dimapur and grew up absorbing the magic of this place. This book was made possible because of the love and faith of the citys extraordinary residents. Their lives, despite the everyday hardship, inspired me to complete this project. As an anthropologist, I traced the accounts of ordinary citizens who navigate a ceasefire city like Dimapur. I am grateful to Anungla Zoe Longkumer, Tali Angh, Alobo Naga, and Kevi Kiso for helping me connect with the social life of music in the city. I also owe my gratitude to Senti Toy who fostered my intellectual curiosity about the transformation of music in Naga society. Her music, writings, and friendship made me reflect upon the concepts of audibility and musical sensibilities. A community of elders and hunters from Dimapur shared their wisdom and accounts of hunting, and opened up my world to an enchanting yet complex world of urban hunting. The wit, terror, and violence involved in hunting, I hope, will initiate conversations about animals and humans who cohabit in frontier urban spaces like Dimapur. I would also like to thank Abraham Lotha for his generosity and friendship over the last decade during which we shared notes about Naga nationalism and anthropology. His role in documenting the life of our Naga leader Late Khodao Yanthan helped me gain an important insight about the politics of belonging and homeland. I am extremely grateful to the team at Home Trust Shop, a coffin store. They are responsible for showing me the everyday experience of living and dying in a ceasefire city.

I also want to thank Nchumbeni Merry for her generosity and time during my fieldwork in Dimapur. She fed me and made sure I had a home to rest. Mhademo Kikon helped me with the logistics of fieldwork; Azung and James offered their hospitality, food, and wonderful friendship; and Susan Lotha took me for a lovely walk around the ADC Court colony and shared her experiences of the city. Akum Longchari and the Morung Express team have always inspired me to embrace Dimapur and engage with the city and its residents. I deeply treasure their friendship and affection. I am grateful to the tribal associations in Dimapur who allowed me to attend their community meetings, picnics, and cultural events.

Finally, I would like to thank my family for being my greatest supporters. The affection of my sisters Julie and Rosemary goes beyond any academic writing project. My mother Mhalo Kikon raised me as a single mother in Dimapur. This book is for your irresistible tribal spirit of survival and living life with courage. My father-in-law Bijoy Barbora and my sister-in-law Moushumi are my biggest cheerleaders, and it is impossible for me to put it in words how dearly I hold them in my heart. Mhademo, Longshibeni, Kimiro, Samantha, Ishaanee, Chichano, and Tuki: all of you allow me to dream about a meaningful future. And my gratitude to Sanjay (Xonzoi) Barbora, my beloved partner who has supported me throughout the course of this project. Thank you, as always, for your patience and wisdom. To the readers ready to flip through the pages of this book, thank you because you will never ever ask me again, So, where is Dimapur?

Dolly Kikon

I would like to thank my co-author and dear friend Dolly Kikon, my friends and family, and the multitude of people in Dimapur who helped with this research.

Duncan McDuie-Ra

In academic research, the challenge for researchers is to convince their peers and audience that the research is significant, that it is worthwhile. During our research in Dimapur, a far greater challenge was convincing the citys residents, the people who know the cityor at least patches of itintimately, that the city itself is even worth talking about. This project began as an exploration of tribal masculinity in 2015. In the course of that research, it became clear that Dimapur was becoming the arena where masculinity plays out, where it is challenged, re-asserted, and fragmented. It is where anxieties over migration, poverty, wealth, corruption, and gender have produced urban crises. These crises happened during the life of this project, and this is the point from where the city took over as our focus. Soon it was clear that Dimapur is not simply an arena or stage for the performance of gender and identity politics or for experiments in different forms of governance; rather, the city is both an arena and a performer. : 3). This is an invitation to think of the urban landscape not just as an arena or stage but as a machine. If Dimapur is a machine then the metaphor can be reworked in many ways: a broken machine, certainly, but also a machine that hums away, with half of its parts missing or dangling off the sides. The machine keeps going, more parts get added, it sucks in more energy. People fight over it; they are repulsed by it. It breaks down often, and people want to fix it. Yet, those charged with fixing it disagree on what is to be done and even on the nature of the breakdown itself. Some even struggle to see the machine they are to fix.

We encountered this all the time. Once we started to put the city at the centre of the project, the relationship between the city and its residents began to emerge, and it usually emerged when we first broached the topic. Whenever we told respondents, friends, and acquaintances that we were writing a book about Dimapur, their usual response was confusion: Were we really writing a book about the city? This city? Such a response was not a surprise, as we will discuss later in the book, Dimapur remains off the map for most people, even its residents. This response would be unlikely if we were writing about Mumbai or Chennai or even a medium-sized city like Amritsar. These are cities with glorious pasts, alternative lives and circulations in literature and film, and arenas where events of consequence to mainstream India have taken place. They are on the map. Dimapur is not. Despite this, we must point out here that Dimapur has been embroiled in the everyday militarization and violence of Asias longest-running separatist conflictthe Indo-Naga armed conflict. Along with numerous security camps of the Indian Armed Forces, two designated ceasefire camps of the Naga insurgentsthe National Socialist Council of Nagaland Isak-Muivah (NSCN-IM) and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Unification (NSCN-U)in the peri-urban areas make Dimapur an exceptional city.