Stephen D. Rosenberg - Time for Things

Here you can read online Stephen D. Rosenberg - Time for Things full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Time for Things

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Time for Things: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Time for Things" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Time for Things — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Time for Things" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Contents

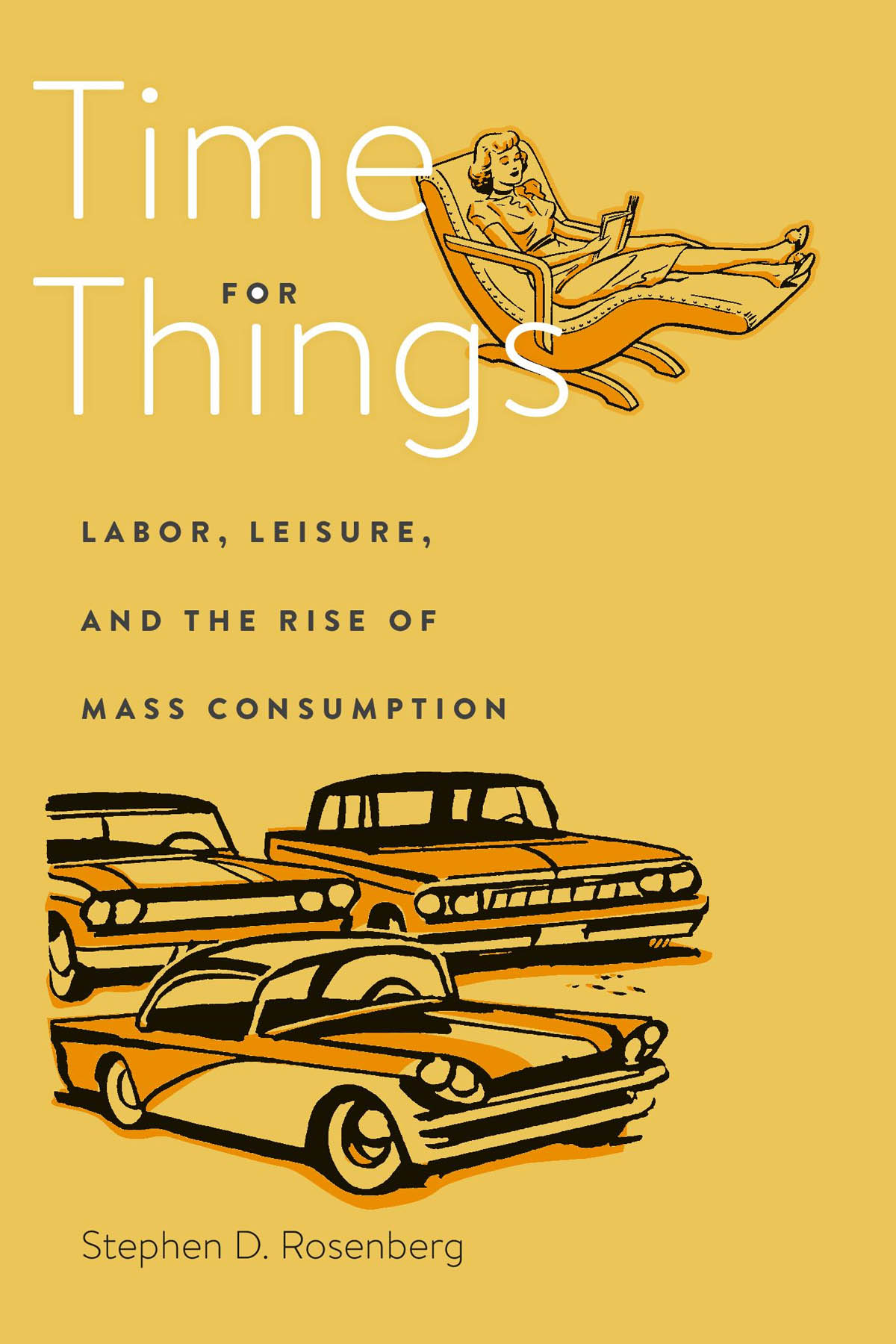

Time for Things

Time

FOR

Things

LABOR, LEISURE, AND THE RISE

OF MASS CONSUMPTION

Stephen D. Rosenberg

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2021

Copyright 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First printing

978-0-674-25052-9 (EPUB)

978-0-674-25053-6 (MobiPocket)

978-0-674-25054-3 (PDF)

978-0-674-97951-2 (cloth)

Cover design by Tim Jones

Cover images courtesy of Getty Images

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Rosenberg, Stephen D., 1966 author.

Title: Time for things : labor, leisure, and the rise of mass consumption / Stephen D. Rosenberg.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016849 | ISBN 9780674979512 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Welfare economics. | Consumption (Economics) | Quality of life. | Incentives in industry. | Quality of products.

Classification: LCC HB99.3 .R654 2021 | DDC 330.12/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016849

Contents

Time for Things

In 1930, against the backdrop of the Depression, John Maynard Keynes wrote a short essay entitled Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren in which he cast his gaze beyond the economic ferment of his times to prognosticate about the future of capitalism. Abandoning for a moment the short- and medium-run temporalities of his discipline, as well as the economists preoccupation with scarcity and dismal trade-offs, Keynes became entranced by a much brighter vision. Economic growth would, in Keyness view, eventually bring about an end to toil. A renaissance of human civilization would ensue, a cultural flowering reminiscent of the classical Greek ideal (or perhaps that of bohemian Bloomsbury). However, this one would not be bought at the expense of an army of slaves (or a household full of servants) but rather would be secured through exponential economic growth. Keyness reasoning was straightforward enough. He simply took the estimated historical growth rate of capitalist economies and projected it over the following one hundred years. Assuming past rates of productivity improvement would continue unabated for the next century, the economy would, over that period, grow eightfold in per capita terms. Mankind is solving its economic problem, Keynes proclaimedsuch, he reflected, is the almost magical power of compound growth. Similarly, when Keynes looked back at the trend in work time in industrial capitalism over the previous fifty years, he saw a pattern he had no reason to believe would not continue. Increasing productivity had led to a steep and continuous decline in the length of the work week between 1870 and 1930, with working hours dropping by 30 percent in Europe and the United States. In predicting the future of capitalism, Keynes simply posited the continuation of that trend.

The conclusion Keynes drew from his brief exercise in futurology was that the productivity gains yielded by capitalism would, in the long run, inevitably lead the economy to enter into a stationary (or steady) state, in which material wants would be satiated. Further increases in productivity would then have the effect of reducing the need for labor, radically diminishing the length of the working week. The result would be an utter transformation in the moral fabric of capitalism, returning pecuniary motive to the marginal place it held in previous eras of history and opening up new possibilities for human flourishing. Keynes predicted that in the coming era of abundance, we shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. To be sure, there would be a period of adjustment during which people would have to cultivate the skills and sensibility necessary for them to be able to fully enjoy their liberation. Indeed, Keynes thought that such is the cultural momentum, under capitalism, behind work for works sake, that people might for a while voluntarily arrest the decline in work hours. He imagined people resisting working for fewer than fifteen or so hours each week, for no good reason other than to keep themselves busy. But they would certainly not choose to work more than that, for three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us (Keynes 1930, p. 369). In effect, capitalism, conceived of as a system of self-exploitation and the fetishistic pursuit of monetary gain would abolish itselfor, more precisely, would evolve into something utterly differentsimply by virtue of following its natural developmental trajectory. The Faustian pact made at the dawn of the modern era, having achieved its goals, was thus destined to be undone. Purposive man, to use Keyness phrase, would be laid to rest, having served his purpose admirably.

In 2005, a group of eminent economists, including such luminaries as Robert Solow, Joseph Stiglitz, and Gary Becker, was invited to contribute essays to a book intended to evaluate Keyness predictions about the future of capitalism (Pecchi and Piga 2008). The historical data analyzed by these economists showed that Keyness growth projections were, if anything, on the conservative side. His predictions for growth, based on a long-run estimate of about 2 percent per year, yielded an upper bound eightfold increase in per capita wealth over the next hundred years. Fabrizio Zilibotti found, however, that in the fifty-year period between 1950 and 2000, average world economic growth was 2.9 percent per year, quadrupling per capita output.

Economists offer a range of explanations for the failure of Keyness prediction, some of which are close to being circular. One explanation is that work is itself a source of utilitysurely that must be so, the reasoning goes, or else why would people not choose to cut their hours? Alternatively, material wants must indeed be insatiablewhy else would people choose income over leisure? Other explanations offered are more substantive: consumption under conditions of affluence becomes driven by status-seeking one-upmanship, and the demand for positional goods (which index relative position in a status hierarchy) can never be exhausted; growing inequality induces a widespread fear of downward social mobility and so increases the incentive to work in order to close the income gap; higher income creates new needs, such that needs are not fixed but rather change with economic growth. These explanations surely have something to them. No one could sensibly deny that some people find some value in activities for which they happen to be paid, nor would it be wise to underestimate concerns about status and the role of conspicuous consumption in status competition. However, the explanations offered do not, for reasons set out in the next chapter, satisfactorily account for the dramatic degree to which Keyness vision of the future failed to come to pass. Indeed, the very fact that there is such disagreement between the economists on why, in the wake of growing affluence, work failed to retreat more than it did, indicates the difficulty of the puzzle.

Closely related to the question of why work hours failed to decrease more as productivity went up is the question of why consumption continued to increase so relentlessly. Productivity gains, in lieu of reduced work time, were turned into higher real income, which was used to fund more consumption. Why is consumption, like production, seemingly unbounded under capitalism? There is clearly a plausible explanation for the unending expansion of capitalist production: Capitalists try to outcompete one another by increasing productivity, seeking to turn lower costs into a bigger market share by cutting prices and expanding output. Yet it is not at all clear why effective demand should keep up with expanded outputwhy, in Keyness terms, the demand for commodities should prevail over the demand for free time, even though the relative value of those commodities should, it seems, decline with growing affluence. This ongoing growth in consumption is especially puzzling given evidence that suggests that the relation between wealth and well-being is far from being a simple linear one in which added increments of wealth add increments of well-being.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Time for Things»

Look at similar books to Time for Things. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Time for Things and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.