Naguib Mahfouz - After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994)

Here you can read online Naguib Mahfouz - After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Gingko Library, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994)

- Author:

- Publisher:Gingko Library

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First English edition published in 2020 by

Gingko

4 Molasses Row

London SW11 3UX

First published in the arabic by Dar Al Masriah Al Lubnaniah

Copyright 2015 Dar al Masriah al Lubnaniah, Cairo

English translation copyright 2020 R. Neil Hewison

Introduction copyright 2020 Rasheed El-Enany

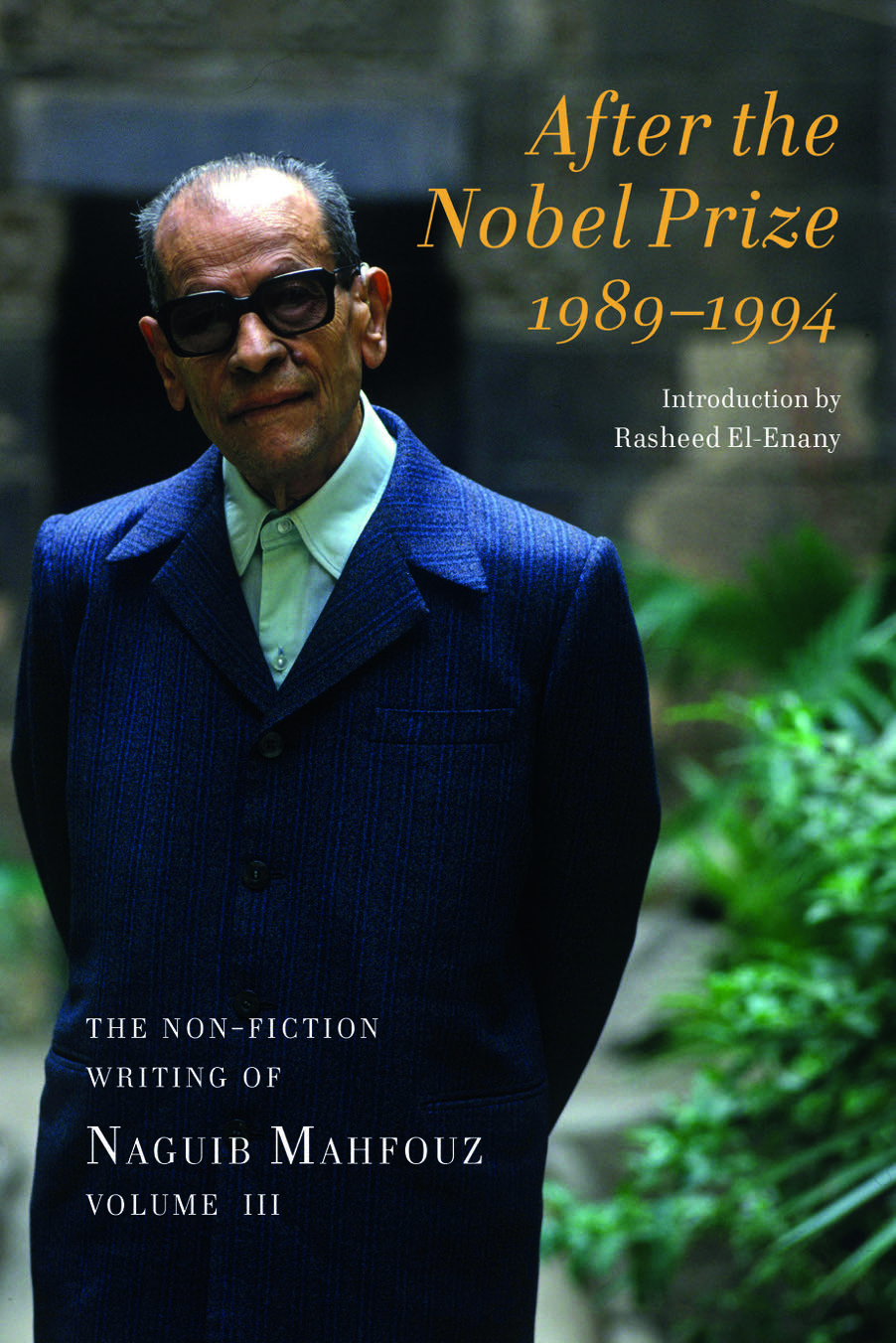

Jacket image: Naguib Mahfouz pictured in old Cairo in 1989 (courtesy: Alamy).

A CIP catalogue record for the book is available from the british Library.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, no part of this book may be

reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information

storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-909942-13-4

eISBN: 978-1-909942-14-1

Typeset in Optima by Macguru Ltd

Printed in the united Kingdom

www.gingko.org.uk

On 14 October 1994, an impoverished young man, under the influence of fanatic religious instigation, tried to assassinate Naguib Mahfouz by stabbing him in the neck as he was about to be driven by a friend to a gathering somewhere in Cairo; hence the cut-off date of the essays assembled in this volume. Following the attack, which he miraculously survived, Mahfouz was left unable to use his writing hand and his weekly column in Al-Ahram newspaper, of which this is a collection, stopped for a while, to be continued later in a different format. As I was getting closer to the end of the articles, a growing feeling of uneasiness gradually took hold of me. Turning to the article dated 12 October 1994, a cold shiver ran down my spine, as if I were living through a countdown to the stabbing incident. Two days after the publication of that article a knife was going to make its way to the neck of the great man, who would have been smiling affably and raising his hand in a greeting motion at the young man he thought was approaching to greet him, as strangers often did when they saw Mahfouz. In my horror, I cannot help but think that at that moment the knife must have resented its inanimate state which made impossible an opposition to the action it was being directed to do. Like the rest of us, Mahfouz, being no privy to the future, had no idea that two days after publishing an article titled Good Morning to the World a terrorist attempt would be made on his life.

I continued reading the articles of October 1994 with mounting anxiety and trepidation. How could he go on writing, week after week, as if nothing was going to happen? He must be warned! The imminent doom must be intercepted! Someone must scream in alarm in the face of the unknown! On 12 October, he writes that we live in a world replete with offensive things, and it is rare to come across something pleasing, yet he concludes his article with characteristic stoicism, calling to his readers to open your newspaper, and do not despair of taking in what is better and brighter. How ironic! Two days later those same readers were going to open their newspapers to read the news of the attempted murder of their beloved author. During the rest of the month and while Mahfouz was fighting for his life, Al-Ahram published two more articles penned by him, dated 20 and 27 October: he had written and submitted them ahead of schedule, as he often did.

In the first, titled From Enlightenment to Comprehensive Reform, he writes of terrorism as a symptom of the absence of social justice: extremist ideas and calls to terrorism may find an echo in souls that are exhausted by poverty, despair, and feelings of injustice. This is an argument he repeats ad infinitum throughout the essays of this book and elsewhere in his fiction and non-fiction writing. For him, terrorism is a social phenomenon with underlying causes which could not be resolved through security measures but through democracy, education and social justice. In the second article, titled Pathological Tensions, he points out that all discussions in society are marked by the overwhelming stamp of vehemence and violence. He further laments that people cannot bear other opinions and have become lacking in any kind of understanding or tolerance, and that the climate of terrorism has gained ground in literature, thought, and debate. He concludes by blaming all these serious faults in society on the damage caused by living far too long under totalitarian regimes. It was as if Mahfouz, in writing these articles, immediately before the incident, was prophetically running ahead of everyone in trying to explain and place in context the terrorist attempt on his life that was about to happen. In fact, this entire volume with its scores of essays written over a five-year period strangely leads up to a state of mind with which the assassination attempt does not come as a shock.

Mahfouz writes about a polarised society: one bereft of its old values; one where democratic government is a sham and an emergency law giving the state huge freedom-curbing powers has been habitually renewed since the assassination of Sadat in 1981; where social inequality is paramount; corruption is rife; and where fundamentalist intolerance has taken root and adopted armed struggle as the means to resist an unjust authoritarian state. If we look at the first essay in this volume, dated 19 January 1989, we find that its title alone says it all and paves the way to 14 October 1994: Towards a Society Not Based on Violence. If anything, Egyptian society five years on was even more deeply mired in violence, such that one of its greatest writers and a lifelong defender of the rights of the underprivileged was not safe from assassination in his old age.

The period covered by the essays in this volume, 19891994, was eventful both in a regional and international sense. This is the period that witnessed the end of Communism and the Cold War, marked by the fall of many totalitarian regimes in Eastern Europe and the emergence of democracy. In the MENA region, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, followed by a war to liberate Kuwait led by the USA. There was also the start of the Algerian civil war in 1992 following the cancellation of election results that would have brought to power the Islamic party of FI S (Islamic Salvation Front). Mahfouz engages with all these events with vigour and clarity of vision, but above all with the constancy of thought and principle that characterised his writing from start to finish. Freedom, democracy and social justice are recurrent words in his vocabulary; they are like keys that open the door to his thought and the positions he takes in relation to public events.

A committed socialist all his life, on 26 September 1991, shortly before the official dissolution of the Soviet Union, he writes an article titled The Russian People, in which he extols the Russian people for having written a shining history for themselves in the experiment of human civilisation. He sees them as having undertaken the realisation of the dream of millions of people to create the desired paradise in this life. For this end they had to endure persistent hardship, suffer immense sacrifices [] and do without human freedoms, and human rights. According to Mahfouz, the failure of the Communist experiment can be ascribed to the totalitarian methods of the regime that applied it: If the Communist project had been founded on a democratic system, it would have been established in an atmosphere of liberty and would have benefited from the successive criticisms of its economic and philosophical systems and followed a beneficial development, cleansing it of all the negative aspects that brought it down. For him, totalitarianism is an abhorrence, as he expounds in an earlier article tellingly titled A Disease Called Dictatorship, where again he laments the failure of the great project of Communism because of the repressive regime that put it in practice, allowing cruelty, rampant corruption and the crushing of individual dignity. He describes dictatorship as the first foe of humanity, and in a language untypical of him but which reflects the intensity of his feelings on the issue, he writes: A curse on dictatorship and dictators! They have tainted history with blood and shame, and there is not one fool among them who has not left behind him a nation stripped and torn apart, its hopes destroyed. By contrast, he sees democracy as a way of life that cannot be matched [] by any other. However, he entertains no illusion that democracy is immune from failings and problems; the difference he points out is that under autocracy problems become excessive when they are secure from scrutiny and beyond hope of change.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994)»

Look at similar books to After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book After the Nobel Prize (1989-1994) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.