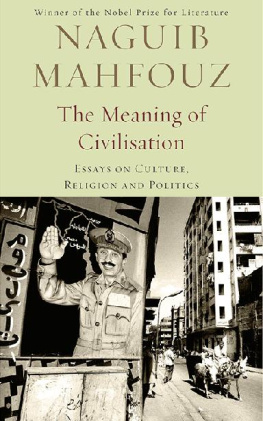

The Meaning of Civilisation

Essays on Culture, Religion and Politics

The Non-Fiction Writing of Naguib Mahfouz Volume II

As a citizen Naguib Mahfouz sees civility and the continuity of a transnational, abiding, Egyptian personality in his work as perhaps surviving the debilitating processes of conflict and historical degeneration which he, more than anyone else I have read, has so powerfully depicted.

Edward Said

One of the greatest creative talents in the realm of the novel in the world.

Nadine Gordimer

He is not only a Hugo and a Dickens, but also a Galsworthy, a Mann, a Zola, and a Jules Romain.

London Review of Books

Mahfouz embodied the essence of what makes the bruising, raucous, chaotic human anthill of Cairo possible.

The Economist

Contents

Introduction

by Rasheed El-Enany

The volume to hand contains the essays of three separate volumes originally published in Arabic, namely On Culture and Education (1990); On Religion and Democracy (1990); and On Youth and Freedom (1990). They represent the first collections of Mahfouzs short current-affairs column in the Egyptian daily, Al Ahram , published weekly with the generic title wijhat nazar or a point of view. The volume to hand adopts a chronological arrangement of the essays, unlike the Arabic volumes which attempted three loose thematic groupings as suggested by the titles but at the expense of the chronology restored here. Nor does the current volume contain all the essays in the aforementioned three volumes, since it is limited to the Sadat years when Mahfouz started his column in 1974, and stops at the end of 1981, the year Sadat was assassinated. The rest of the essays will appear chronologically in future volumes of this series of Mahfouzs non-fiction writings.

Some of the essays are rather dated and closely related to the affairs current in their day, and particularly in Egypt, such that they would only make sense to a contemporary of the time of their writing, or a specialist steeped in the study of the period. As such, they are a valuable window into the era that produced them and what Mahfouz thought concerning the happenings of the day. Their greatest fascination for a literary scholar like myself is in comparing these stark expressions of Mahfouzs social and political thought with the same, clad in the intricate texture of his fiction. Questions of uniformity and inconsistency are bound to be of interest. The range of topics is immense in both variety and range: political pluralism; religious education; overstaffing in government departments; corruption; film censorship; elections; scientific research; public morality; Egypts debts; authors rights and piracy, etc. In what follows, I shall offer some disparate observations that arise from reading this vast number of little essays.

Mahfouz can fall into oversimplification as when in the article Religion and School he reduces the teaching of religion to that of good behaviour with pupils achieving the highest grade in the subject based on their treatment of their classmates and teachers, etc., not to mention his ignoring of the complex issue of how to teach religion to classes of mixed faith, given that Egyptians are made up of Muslims and Christians. He had treated the complexity of this issue beautifully in a short story titled Jannat al-Atfal or Childrens Heaven, from the collection Khammarat al-Qitt al-Aswad or Black Cat Tavern (1969) where a hapless father reels under the innocent but ruthless investigation by his little girl on why she and her Christian best friend have to be separated during religion classes at school. The sensitivity shown in the fictional treatment is lost in the article without trace.

Worse still is when Mahfouz falls into self-contradiction. In an article titled Islam and the Battle of Ideologies, he puts Islam on a par with Western democracy on the one hand, and communism on the other, and goes on to make comparisons between the three ideologies. He even talks of the economic model of Islam and how it differs from capitalism, and falls into the nave identification of the concept of shura or consultation [in affairs of government] in Islam with Western democracy. In doing this he falls unwittingly into the trap of accepting that Islam is not just a religion but a complete socio-political system, something that goes against the grain of his vast novelistic representations to the contrary, not least in his magnum opus, The Cairo Trilogy , where the Muslim Brotherhood, the rising political force of the 1930s and 1940s is ridiculed as an irrelevancy in modern times. Only two weeks later, apparently in response to some readers letters, we find him backtracking in an article titled O God!, arguing that modern man should expect no new revelation from heaven but must make rationality alone the true human means to knowledge. This is more like the Mahfouz we know from his fiction than in the above essay.

Some turns of phrase in these short essays can display a harshness and a cynicism totally uncharacteristic of Mahfouz both as person and as writer, as when he closes an essay on corruption, Millions and Pennies, written at the time of Sadats early attempts at political liberalization, by wondering whether the nation at that moment of its life and in the face or rampant corruption was more in need of policemen, informers, prisons and gallows than of political platforms or parties.

Conversely, his essays can also reflect more blatantly his originality of thought, experimental spirit, and readiness to question received opinion that we have witnessed in his fiction time and again, if often behind a symbolic structure or a metaphorical narrative. In an essay titled Killing your Brother whether He is a Criminal or a Victim, written in June 1976 in the nascent years of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90), we hear Mahfouz admonishing the Palestinians, albeit respectfully, regarding their role in the war, blaming them for having become a state within a state, and reminding them of what he sees as the same role they had previously played in Jordan, which led to the infamous war between them and the Jordanian state in 1970, often referred to as the Black September. Such a stance was not an easy one to take at the time. Progressive writers were supposed to support the Palestinians regardless and to denounce the Lebanese Maronites as a force of reaction. It must have taken courage for Mahfouz to adopt such a position. This can be seen as an indicator of a much more controversial stance that Mahfouz was to take later in support of Sadats peace initiative with Israel in 1977 and the following years against the almost unanimous outcry of the intellectual class in Egypt at the time, not to mention the Arab regimes that sought to ostracise Egypt with the removal of the Arab League headquarters from Cairo to Tunis. In this regard we see him in an essay titled Diagnosing Calamity (1/2/1981) railing at those who ignore that conflicts between nations can be solved either by war or negotiation, but not by a state of no war, no peace, which seemed to be the favourite solution of those who opposed Egypts peace accords with Israel.

Similarly, on 20 December 1976, he calls unabashedly on oil-rich Arab countries to pay back Egypts international debts and to invest their wealth in Egypt instead of the West, reminding them of Egypts wars on behalf of itself and them. It is interesting to note with the benefit of hindsight that that essay, The Philosophy of the State Radio and Television, was written only weeks before the famous bread riots that shook Egypt and Sadats regime in January 1977, and which erupted when state subsidy was lifted from a variety of essential goods in order to satisfy international monetary conditions for more loans. Later that year Sadat was to visit Israel and address the Knesset in a move that took the world by surprise and alienated Arabs, but which was largely attributed to Egypts dire economic situation. As already mentioned, Mahfouz was to support the eventual peace accords with Israel of 1979. But ironically, Mahfouz fell silent over the bread riots, an event that shook the nation and nearly toppled the regime. After regaining control, Sadat ridiculed the popular uprising and labelled it the thieves uprising in a reference to the plundering of posh shops and clubs by the mob that accompanied some of its events. As the contents of this volume show, on this Mahfouz preferred to maintain judicious silence.